Be strong and courageous, and do it (1 Chronicles 28:20)

(Micha Riss collection)

As 1955 dawned, EL AL was still coping with a fleet of World War II-vintage Lockheed Model 49 Constellations and Curtiss C-46 Commandos. It dreamed of the day when modern types could be operated, enabling the company to join the ranks of the world’s leading airlines. New aircraft, used efficiently, could also increase passenger traffic, restore profitability and earn badly needed foreign currency for the young State of Israel.

Many alternatives had been considered, including the acquisition of newer Constellations and improved powerplants for the Commandos. However, EL AL’s management had kept their eyes focused on a bold venture taking shape at the Bristol Aeroplane Company at Bristol-Filton, England, and they were transfixed.

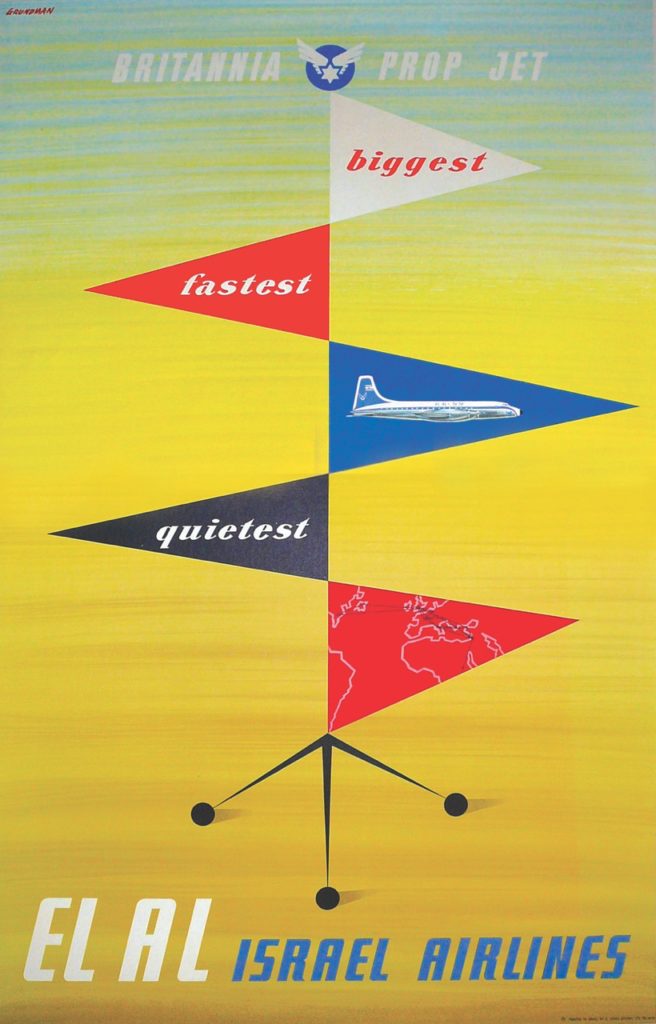

A new engine, the Bristol Proteus turbopropeller, was being developed—for a new airliner called the Britannia—that promised substantial improvements in speed and operating economy. Four Proteus engines powered the Britannia, which was offered in a long-body version, the 100-seat Series 300 that had nearly twice the capacity of a Constellation. This model particularly appealed to EL AL, with a range of nearly 6,900km (4,300mi) with maximum payload, and a cruising speed of 640km/h (400mph) at an altitude of 7,900m (26,000ft). Moreover, the smoother operation of the turboprop engines offered a new dimension in quieter flight and comfort. The Britannia 300’s performance would allow regular nonstop service in both directions across the Atlantic, ideal for EL AL’s requirements. Each Britannia would cost $4.5 million (equivalent to $40 million today), nearly five times the cost of a used Connie— an enormous sum in its day for the young airline and state—but it represented a technological revolution.

After painstaking internal analysis and tough pleading and cajoling with its government shareholder representatives, EL AL announced on 17 March 1955 its bold decision to invest up to $18 million for four Britannias to replace its outmoded fleet, with the hope of operating them on its trans-Atlantic route by early 1957. On 22 June 1955, at a time when only British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) had committed to purchase the Britannia, EL AL signed an order with Bristol, covering three aircraft and an option for a fourth, thus becoming the first non-British customer.

Only one month later, in July 1955, one of EL AL’s Constellations was shot down by Bulgarian MiGs when it accidentally strayed into Bulgarian airspace. Many Israeli officials demanded that EL AL cancel the Britannia order and cut back to ‘essential’ routes only. Debates on these issues were even held in the Knesset, Israel’s legislature. EL AL’s management, however, staunchly supported the Britannia decision, and when Efraim Ben-Arzi was appointed president of EL AL after the 1956 Sinai War, he also strongly backed the decision.

The Britannia became a matter of sink or swim for EL AL because of the required heavy financial and technical commitment. Success would mean a technological leap into the heart of the international airline arena—the highly competitive North Atlantic run. Failure would leave EL AL with a fleet of second-line aircraft and would fuel the arguments of the skeptics who preferred cutbacks in the airline’s role.

EL AL wisely made elaborate preparations to secure a smooth introduction of the innovative Britannias. By the delivery date of the first, over 450 EL AL employees received specialized training for the type at EL AL’s own training headquarters, and some 140 employees received training in the UK.

Unfortunately, the development of the Britannia was plagued with delays, mainly due to unforeseen problems with ice formation in the intakes of the Proteus engines. The planned delivery dates of early 1957 slipped away, frustrating expectations of securing a good head start against airlines that had not ordered similar equipment.

EL AL’s first Britannia (registered 4X-AGA) was finally delivered on 5 September 1957. A 3,860km (2,400mi) nonstop delivery flight from Filton to Tel Aviv one week later was made in 5hr 59min at an average speed of 645km/h (400mph). The arrival occasioned a great celebration at EL AL and coincided with an announcement of the conversion of the option on a fourth aircraft to a firm order. EL AL had entered a new era, one that would establish it for all time within the ranks of the world’s leading international airlines.

Crew training intensified, and further expanded with the arrival at Lod Airport of the second Britannia (4X-AGB) on 19 October and the third (4X-AGC) on 29 November.

Carefully prepared Britannia proving flights ensued to establish the best possible operating techniques. The first roundtrip proving flight to New York was completed on 30 October 1957, allowing EL AL to check out the sophisticated flight deck equipment, all of which performed beautifully. Early in November 1957, the first of four trans-Atlantic proving flights was completed, with the New York to London sector of 5,665km (3,520mi) being flown in 9hr and the London to Tel Aviv segment in 6hr 50 min. In contrast, typical flying time for a Constellation had been 14hr from New York to London, plus the time for a refueling stop at Gander, Newfoundland. On 8 December 1957 another EL AL Britannia covered the New York to London segment in only 8hr 3min.

The most significant accomplishment occurred on 18-19 December 1957 when a Britannia (4X-AGC), on a proving flight under the command of Capt Zvi Tohar, covered the 9,800km (6,100mi) from New York to Tel Aviv nonstop in 14hr 56min at an average speed of 645km/h (400mph). At the time this was the longest nonstop distance ever covered by an airliner.

Turboprop Service

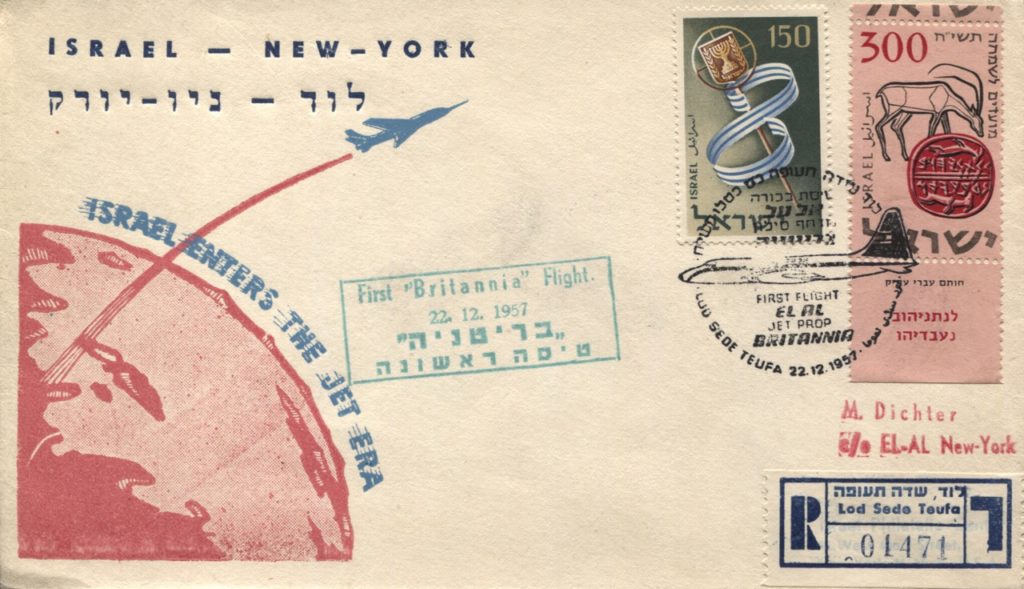

On 22 December 1957, when all other intercontinental airlines except BOAC were still operating piston-engine types, EL AL launched scheduled turbine-powered air service between Tel Aviv and New York (Idlewild, now Kennedy), via London (Heathrow), using Britannia 4X-AGB. This followed BOAC’s introduction of the Series 300 on the North Atlantic by only three days. In the words of Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft, EL AL thereby showed ‘an appreciation of the competitive potential of the [Britannia] aircraft which would have done credit to a company of greater size and much longer experience’.

On the New York to London stage of its inaugural Britannia service, EL AL captured the ‘Blue Riband’ speed record between the two cities with a flying time of 8hr 3min. Although BOAC bettered that on 6 January 1958 with a 7hr 57min crossing, the Israelis snatched the record back two days later, shaving 13min off that time.

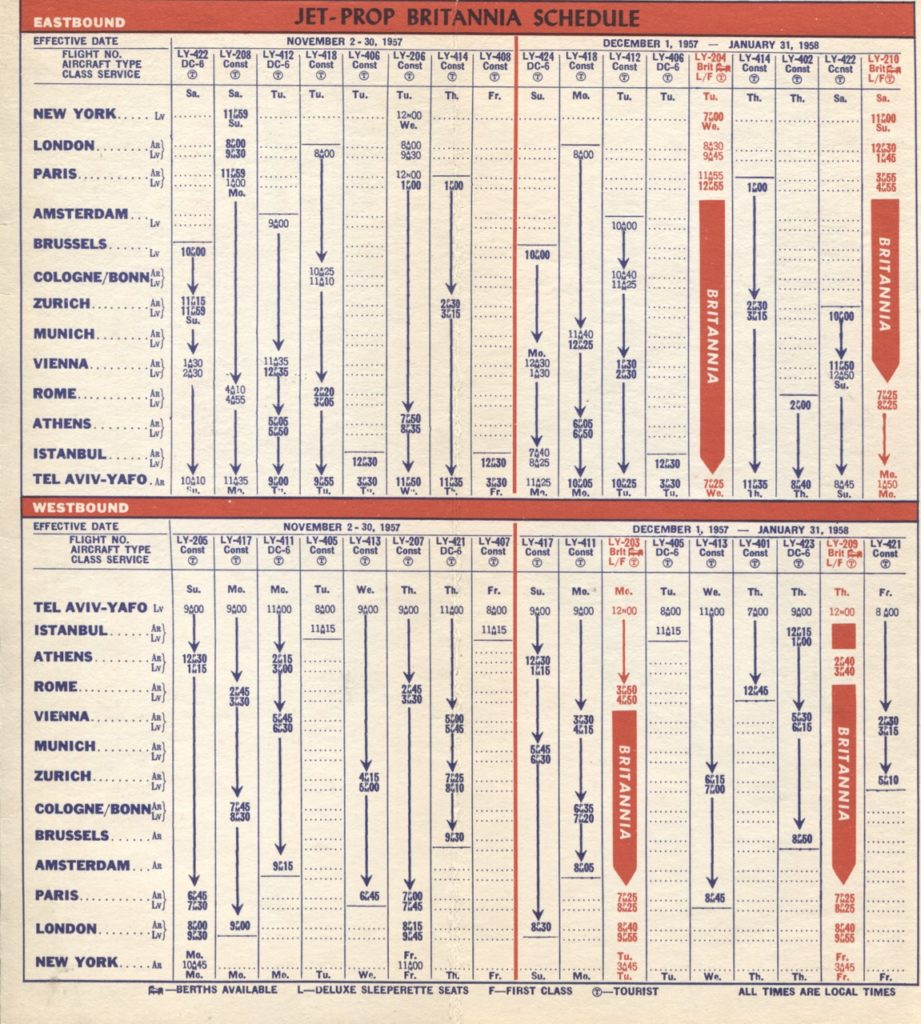

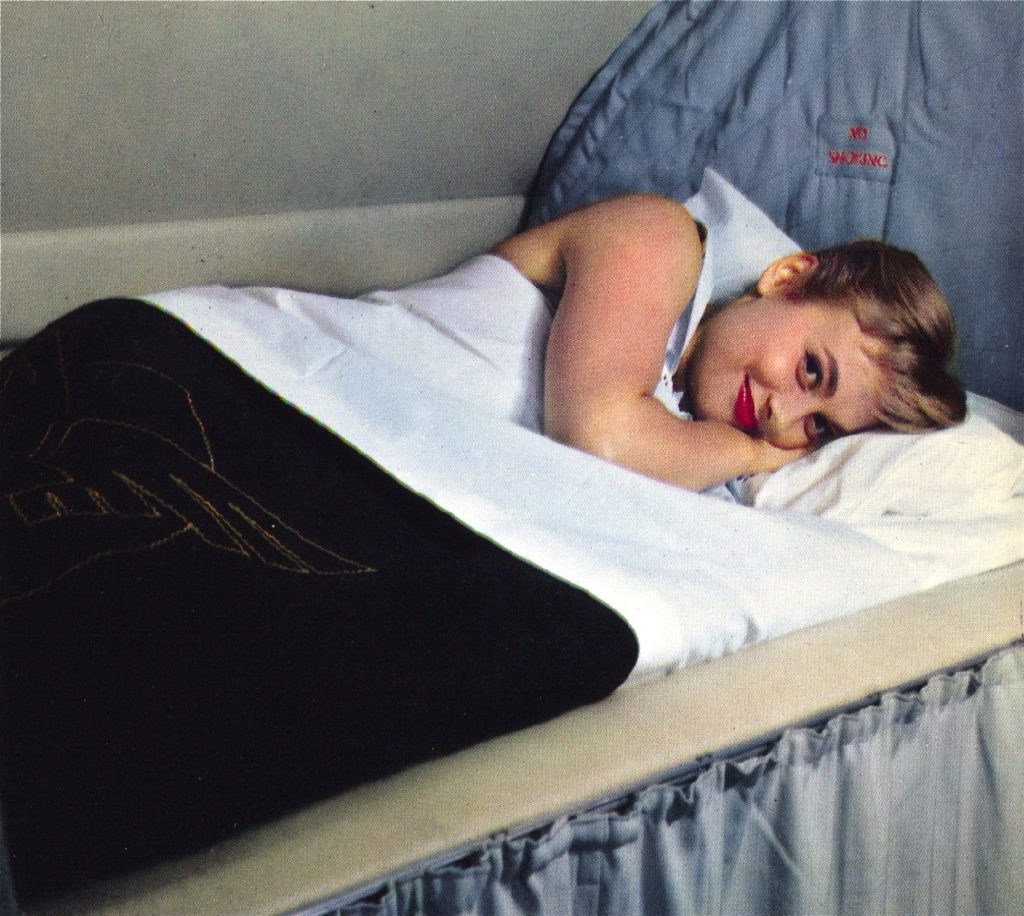

Initially, service was flown once a week, departing Lod each Sunday afternoon, but within three weeks all three Britannias were operating on the trans-Atlantic route via London. The typical passenger accommodation was 18 first class seats—of which four were special ‘sleeperette’ seats and another four were unusually luxurious curtained-off berths—and 72 tourist class seats. As in other propeller-driven aircraft of the day, first class was in the rear, the quietest part of the cabin.

Capt. Zvi Tohar, one of the first native Israelis to become an EL AL captain, in the cockpit of a Britannia at Lod Airport, about 1958. He eventually became chief pilot and later chief of flight operations. EL AL’s usual Britannia cockpit crew complement was four or five. (EL AL Archive)

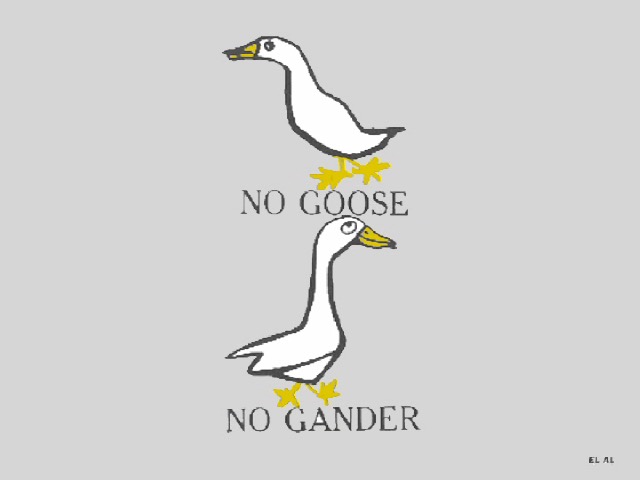

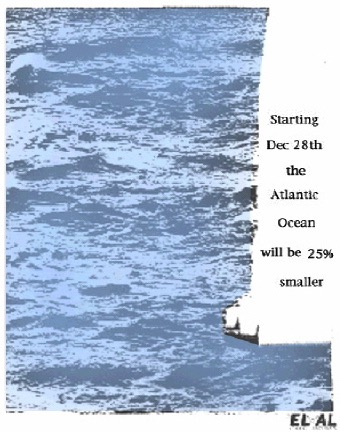

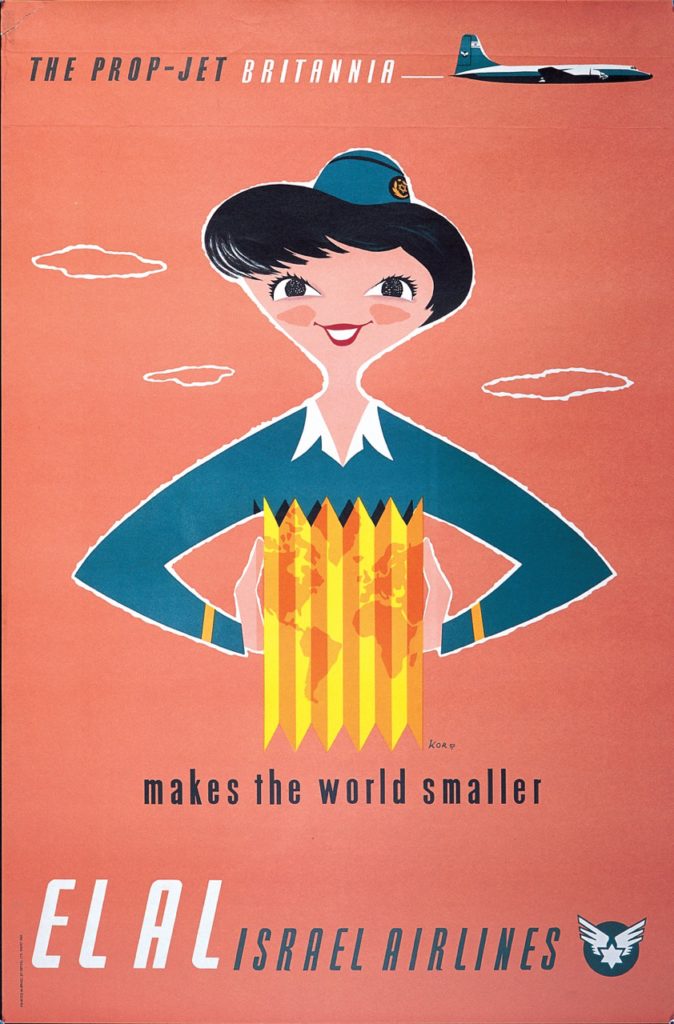

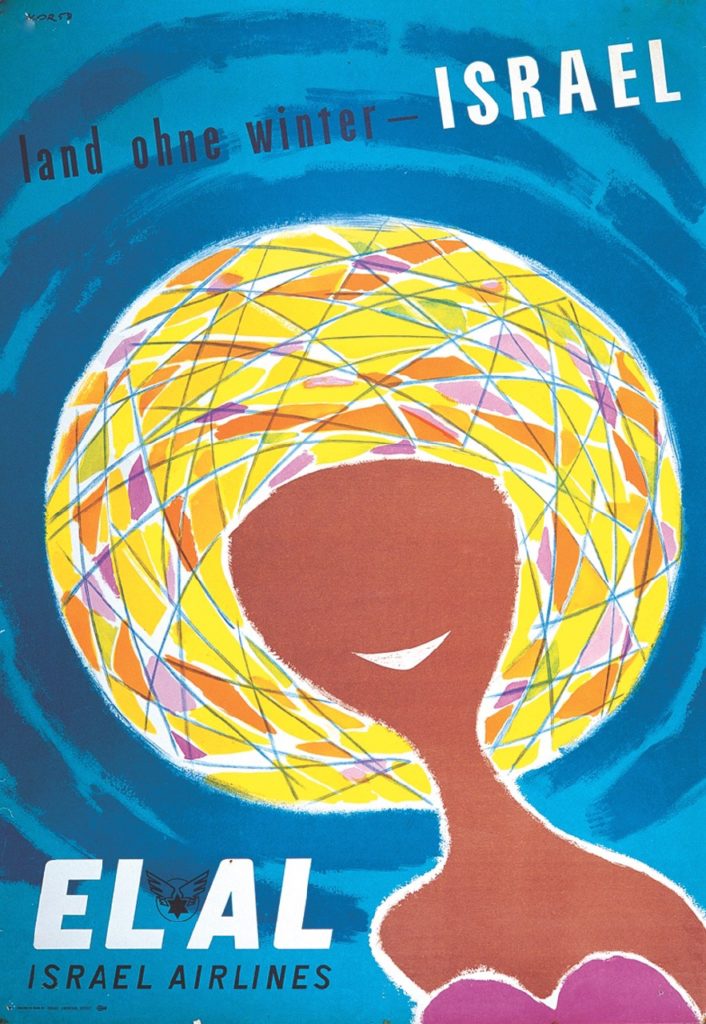

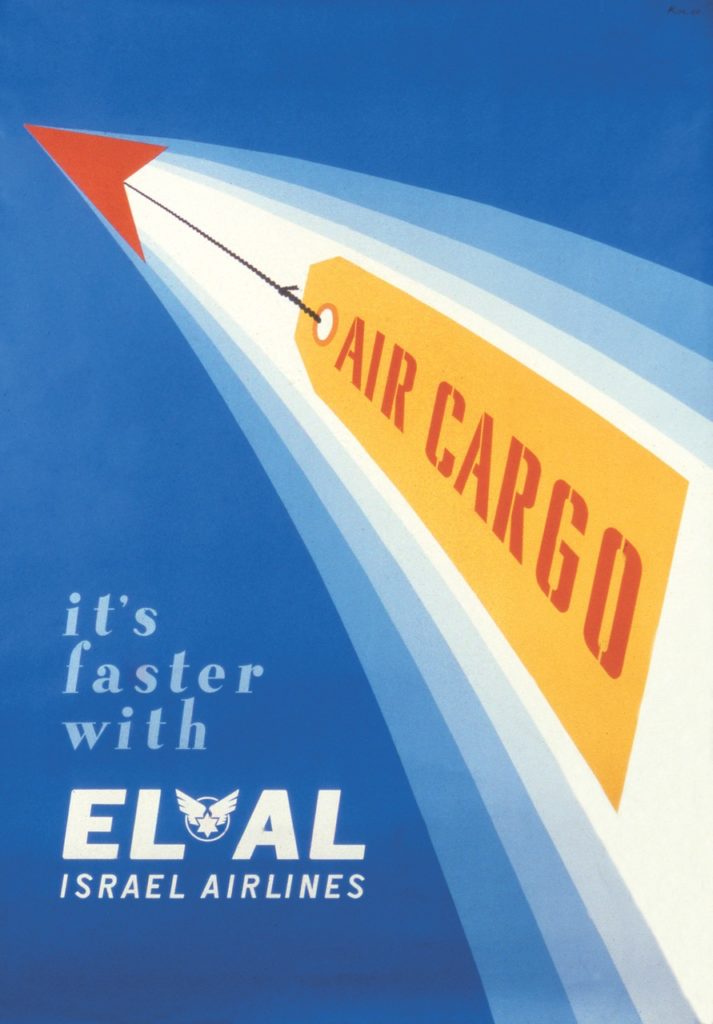

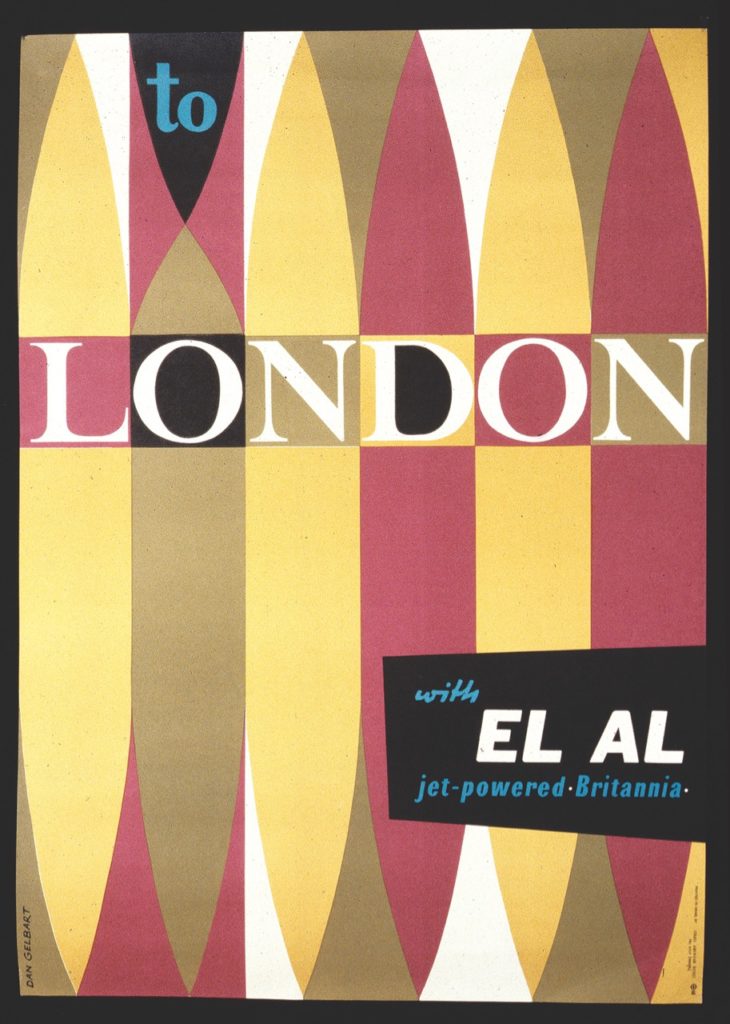

Eager to promote the new turboprop, which had earned the nickname ‘The Whispering Giant’, EL AL launched one of the most famous airline advertising campaigns of all time. Eye-catching proclamations such as ‘No Goose…No Gander’ told customers that the Britannia eliminated the frequent need on westbound trans-Atlantic crossings (because of headwinds) for refueling stops at Goose Bay, Labrador, or Gander, Newfoundland. With another bold advertisement, ‘We Have Cut the Atlantic Ocean by 20%’, the then-existing taboo of drawing attention to long-range over-water operations was ignored in order to emphasize the Britannia’s speed. EL AL approved a substantial advertising budget under its New York public relations head J Peter Brunswick, a former Royal Air Force officer and journalist. Brunswick chose an advertising agency that was relatively new at the time, Doyle, Dane and Bernbach (now DDB Worldwide), which produced some of the greatest airline ads ever.

A sharp rise in EL AL passenger traffic confirmed the Britannia’s success. In the first four months of turboprop operations, EL AL achieved higher passenger load factors than any other trans-Atlantic carrier, reaching almost 70% by the end of April 1958, a remarkable accomplishment in those days. Ever since, EL AL has retained one of the top load factor positions of any airline on the North Atlantic.

Via Britannia to the Top

EL AL’s utilization of the Britannia dramatically illustrated how a small airline, with top quality planning and training, could become a shining example of a first class efficient operation.

Even before Britannia service started, EL AL set a primary goal of making almost all trans-Atlantic flights nonstop. J E D Williams, manager of technical planning and development, initiated an intensive study to see how the Britannia could be operated most efficiently. All known variables were considered, including prevailing winds, payload and fuel burn; and hundreds of hours were invested in crew training and route proving.

The airline learned that if westbound flight time exceeded 12hr 20min, a refueling stop at Goose Bay, Gander, or Boston would be required—an interruption that EL AL was determined to avoid. By departing from the Great Circle route (the shortest distance route) in search of better wind conditions, an average of 55 minutes could be saved. Also, as fuel was consumed and the aircraft became lighter, fuel burn could be reduced by allowing the aircraft to drift upwards about 245m (800ft) per hour, from an initial cruising altitude of about 6,700m (22,000ft) to 9,150m (30,000ft). Procedures were adopted to vary this general plan according to the winds experienced at these levels.

Using these techniques EL AL consistently outstripped BOAC (as well as everyone else) across the Atlantic. During the first 11 months of Britannia operations, EL AL completed over 300 trans-Atlantic trips, and more than 90% were made nonstop. Whenever a technical landing had to be made, it was caused by unusual weather, traffic or load conditions.

Moreover, EL AL consistently was faster across the Atlantic than BOAC, both in scheduled and actual flying times. EL AL scheduled 10hr 50min for the London to New York run, with the return at 8hr 30 min—both less than BOAC’s timetable. Yet EL AL often beat its own schedule. For example, on 10-11 March 1958, a London−New York flight (by 4X-AGA, commanded by Capt. Sam Lewis) made the crossing in 9hr 23min—a new westbound speed record and 87 minutes less than scheduled. In another typical example, an EL AL Britannia would leave New York for London eight minutes later than its BOAC counterpart and be parked on the ramp at Heathrow by the time the BOAC aircraft landed. This performance made EL AL the envy of other trans-Atlantic carriers.

Route Developments in the Late 1950s

Improvisation in Africa

Since the establishment of the State of Israel, hostile Arab states prevented EL AL from passing over their airspace. EL AL’s route to Johannesburg, South Africa, which opened in 1950, was confined to flying from Tel Aviv south towards Eilat and over the Gulf of Aqaba, Straits of Tiran and Red Sea, down to Nairobi and Johannesburg. Starting in late 1955, Egypt claimed control on airspace over the Straits of Tiran, forcing EL AL to cancel its direct route to Johannesburg along the east coast of Africa. An alternative much longer route was available through North and West Africa, but the countries concerned objected to EL AL-marked aircraft landing in their territories.

EL AL accordingly charted Douglas DC-6B and later DC-7C aircraft from SABENA, the Belgian airline. These flew from Tel Aviv to Benghazi or Tunis on the North African coast and then south via Kano, Nigeria, or Fort Lamy, Chad, and Léopoldville or Brazzaville, Congo, to Johannesburg. This arrangement continued until 1962 when EL AL introduced its own Boeing 720B jets to Johannesburg on an even more circuitous route, via Teheran, Iran (see Chapter 5).

Britannia Expansion

For summer 1958, EL AL’s first peak season with the Britannia, all three aircraft flew regularly between Tel Aviv and New York. At the height of the summer, five trans-Atlantic flights per week operated in each direction, via London or Paris, or both. Annual trans-Atlantic passengers more than doubled, from 8,000 to 19,000, and EL AL’s overall share of traffic also doubled—within one year.

The Constellations were now completely displaced from the trans-Atlantic route via London or Paris, but remained in service to other European cities, including two new destinations added in early 1958 that evoked poignant emotions: Cologne and Munich, Germany.

On 7 March 1959 EL AL received its fourth and final Britannia (4X-AGD) and returned a temporarily leased one (4X-AGE) to the manufacturer. Trans-Atlantic traffic continued to rise, to 25,000 passengers in 1959 and 32,000 in 1960. Within the European network, the Britannia replaced the Constellations, and in 1959 inaugurated service to Teheran, Iran.

Operation Eichmann

In 1960 the Israeli government called upon EL AL to help carry out a unique and daring operation. That year, the Mossad, Israel’s secret service, determined positively that Adolf Eichmann, one of the most notorious war criminals of Nazi Germany, was living in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Between 1942 and 1945 Eichmann was largely responsible for the logistics of exterminating millions of Jews, and other victims of the Holocaust, including organizing their transport to the death camps.

As Israel had several hundred thousand citizens who lost relatives murdered by Eichmann and the Nazi regime, the state had long sought to bring the fugitive to justice. Argentina would not assist, so the Mossad, headed by Isser Harel, developed an astonishing plan to capture Eichmann and secretly transport him to Israel on an EL AL Britannia.

The chosen moment for implementing this plan coincided with the 150th anniversary of Argentina’s independence. Also, a former EL AL Corporate Secretary, Luba Volk, was then living temporarily in Buenos Aires. She had stayed in touch with EL AL, as mutual interest was expressed in having her establish a Buenos Aires sales office and possibly help start an EL AL route to Argentina in view of its sizable Jewish population.

Acting through President Ben-Arzi and Vice-President Ben-Ari, EL AL engaged Volk to obtain all Argentine permits for a flight to bring an Israeli delegation, headed by government minister Abba Eban, to Buenos Aires for the independence anniversary celebrations. At one point she even tried to sell tickets for the return trip. In Israel EL AL’s Adi Peleg and Baruch Tirosh assisted respectively on security and in organizing the flight crews. The real purpose of the flight—to extract Eichmann to Israel—was not disclosed to Eban or Volk, nor (with the exception of the chief pilot) to any of the crew members and most other participants, who continued to believe it was a purely diplomatic visit.

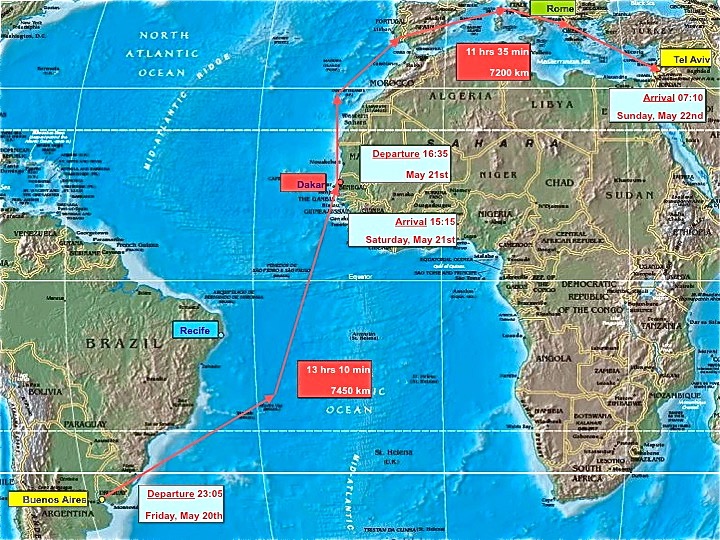

On 11 May 1960 Peter Malkin and other Israeli Mossad agents captured Eichmann on his way home from work, taking him to a ‘safe house’ in a Buenos Aires suburb. The Britannia (4X-AGD), commanded by Chief Pilot Capt Zvi Tohar and with a double crew, duly arrived on 19 May, with Abba Eban and his delegation receiving a warm reception from the Argentine officials.

Meanwhile, EL AL’s Yehuda Shimoni (Manager of Operations) and Joe Klein (Station Manager New York-Idlewild airport), each a Holocaust survivor, had been dispatched to Buenos Aires to assist Isser Harel and his Mossad agents by exploring the local Ezeiza Airport facilities and recommending ways for delivering Eichmann and his captors to the waiting Britannia aircraft.

On 20 May, shortly before midnight, Mossad agents wearing EL AL uniforms appeared at the airport’s security gates dragging another person between them, also in an EL AL uniform, who appeared sick or drunk. In fact, it was Eichmann, drugged for the occasion. They gained entry, hoisted Eichmann up the stairway to the aircraft and deposited him in a seat. Within a few minutes the Britannia’s four turbines began to roar, but the air traffic control tower asked Capt. Tohar to delay the taxiing due to ‘some problem’. Tohar, thinking it related to Eichmannn, sent navigator Shaul up to the tower while keeping the engines running, ready to take off in any eventuality. To everyone’s relief, it was only a minor question about the flight plan. The tower gave clearance. Shaul raced back to the aircraft, and it lifted off the runway for Israel. To prolong secrecy, Tohar omitted a fuel stop in Recife, Brazil and, straining the Britannia’s fuel capacity, flew nonstop to Dakar, Sénégal, in Africa. The aircraft barely made it; immediately upon landing one of the engines lost power and was shut down due to lack of fuel.

Eichmann was ultimately brought before an Israeli court in Jerusalem on charges of crimes against humanity and war crimes. After an emotional public trial, he was convicted and hanged—the only death penalty ever imposed in Israel.

A Brief Reign

By summer 1960 the Britannia was crossing the Atlantic on six roundtrips a week, and had taken over the European network except to Istanbul and Nicosia which were still serviced by elderly Constellations. However, this period proved to be the peak of EL AL’s Britannia operations, as the rising star of pure-jet travel drew near.

As fate would have it, the Britannia entered service a year later than planned. Meanwhile in the United States, at the Boeing plant in Seattle, feverish activity to develop the pure-jet 707 resulted in the type entering service a year earlier than originally anticipated. The 707 started operation over the Atlantic with Pan American in October 1958, three weeks after the de Havilland Comet 4 had entered service over the same route with BOAC—both less than a year after EL AL placed its first Britannia into service. The entry of the Douglas DC-8 in 1959 fueled the fierce jet-powered competition.

That the turbojet would eventually supersede the turboprop on long-range routes was accepted, but the original thought was the Britannia would have a minimum life of five years as a first-rank type. Circumstances conspired to cut the Britannia’s dominant position to ten months.

Fortunately, EL AL did not rest on its Britannia laurels. President Ben-Arzi moved quickly to negotiate the purchase of three Boeing 707-420 Intercontinental aircraft, which entered service in January 1961 (see Chapter 5). Only three years after EL AL’s successful introduction of the Britannia, 707s began to confine the turboprops to the European network.

By summer 1962 nine of the ten competing European and US carriers serving Tel Aviv were using pure-jet equipment. That year 707s took over all of EL AL’s North Atlantic services and the Britannia fleet was reduced in size; the last one was sold in February 1967. EL AL’s Britannia era thus ended less than a decade after its dramatic beginning.

Last updated, 7 July 2021

Copyright 2021, Marvin G. Goldman