“ve–el al yik-ra-u-hu“ — “And they (the Prophets) shall call them to the above” (Hosea 11:7)

Just three months after Israel’s declaration of independence, the Israeli Provisional Government formally decided to establish an airline for the State. The official document, issued 18 August 1948 by the Ministry of Transport headed by David Remez, called for the State to create and invest in one airline as a ‘chosen instrument’ for international civil aviation.

The blockade against Israel during and immediately before the War of Independence sharply emphasized the need for a strong civil airline. Israel was bordered on three sides by hostile Arab States: Syria, Jordan and Egypt (plus non-supportive Lebanon). Only the Mediterranean Sea, forming the western boundary, offered some kind of security. Overseas airlines had abandoned their service to Israel during the war, and the new state obviously could not rely on them to meet its basic needs. From the beginning, therefore, Israel required its own airline to serve as a ‘lifeline’ with the outside world. Moreover, its new air force would require a non-military aviation entity to provide parallel technical capabilities and a reservoir of aviation skills. These are some of the special circumstances that led to the creation of EL AL, and they have greatly influenced its role ever since.

Overwhelming problems faced the creation of a new airline. Israel remained locked in a bloody war, struggling for its very survival. The economy was in shambles, and the government financially insolvent. Meanwhile, the remnants of European Jewry from the Nazi Holocaust languished in displaced person camps in Germany, Cyprus and elsewhere in Europe. Upon arrival in Israel these refugees had to be housed, fed, re-educated and re-established. At the same time, Jews in other Middle East countries, threatened and often attacked in their native Arab lands, urgently needed evacuation to safety and a new life in Israel.

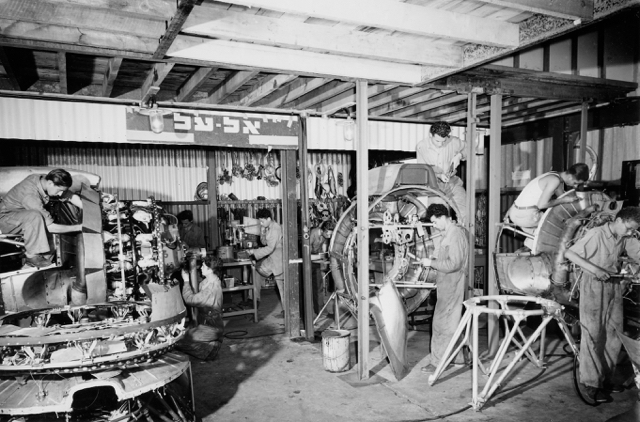

Yet where would the experienced airline pilots and crew be found? The British, during their Palestine Mandate, had sharply curtailed the ability of local Jewish interests to engage in flying, so very few native Israelis had managed to acquire aviation training. Also, the scarce transport aircraft possessed by the state were already overextended for the war effort.

The Israeli military Air Transport Command, where the Mahal foreign volunteers were especially active, contained almost all of the commercial air transport experience at the time. David Remez therefore turned to Munya Mardor, the Air Transport Command’s director, for assistance. However, even before Remez and Mardor could begin, the state was suddenly thrust into creating a so-called national airline.

The First Flight of the National ‘Airline’

In late September 1948 the newly designated first President of Israel, Chaim Weizmann, was temporarily staying in Geneva, Switzerland. The Israeli Government, eager to show the world that Israel was now a truly independent state, wanted to bring him home in an Israeli aircraft. However, their few aircraft capable of making such a journey were in service with the Air Transport Command. Israeli military aircraft were not permitted to land in the United States or in Europe, because of the arms embargo policy of the nations concerned; thus, it was necessary to make the flight under civilian registry and markings. Yet Israel had no airline. The pre-war Aviron had been disbanded and melded into the Israeli Air Force, and the flag carrier proposed by the Ministry of Transport had not yet been formed.

Improvising, it was decided to commandeer one of the two four-engine Douglas C-54 Spymasters of the Air Transport Command. The selected aircraft had been acquired in May 1948 through clandestine intermediaries of the Haganah defense arm and used to airlift arms and materiel from Czechoslovakia, the sole country willing to supply Israel.

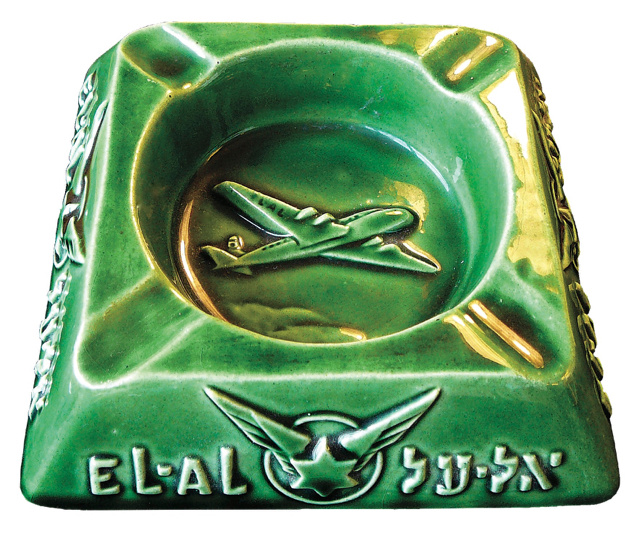

Adopting the suggestion of an Israeli lawyer, Shmuel Szczupak, David Remez named the ‘airline’ EL AL. The title was inspired by the biblical phrase ‘el al‘, from the book of the Hebrew prophet Hosea, meaning ‘to the above’ or more poetically ‘to the skies’.

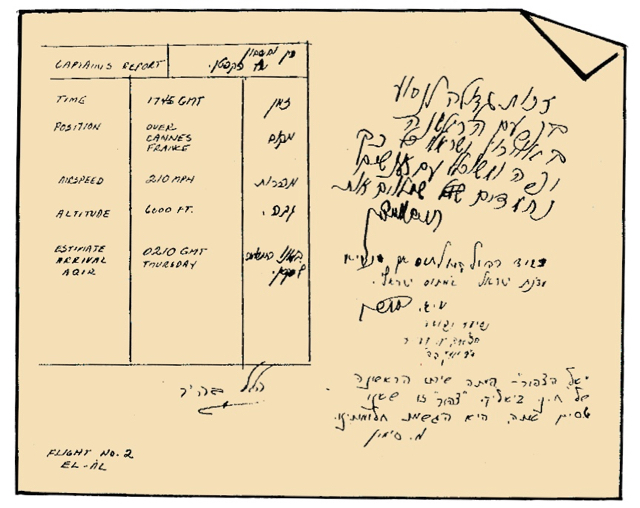

‘EL AL Ltd’ and ‘Israeli National Aviation Company’ titles, in English and Hebrew, were hurriedly applied to the C-54, along with an Israeli flag on the tail. A sofa and other furnishings were added for the comfort of the honored guest and his companions. Extra fuel tanks were installed as there was no country that would permit a landing between Israel and Switzerland. The aircraft received the first entry in the new registration book of civil aircraft of the state, with the registered owner shown as ‘EL AL’. This first entry, dated 27 September 1948, assigned the registration letters 4X-ACA; ‘4X’ was the new international code designating ‘Israel’ for civil aircraft registration purposes.

An all-Jewish crew was recruited mainly from the ranks of the Mahal in the Israeli Air Force. Hal Auerbach and Arnold Ilowite, together with Yitzhak Hennenson, one of the few indigenous aviators, were the three pilots for the Weizmann flight; Munya Mardor, director of Air Transport Command, coordinated the operation.

Blue uniforms, including cuffs and caps adorned with gold braid, were tailor-made in Tel Aviv for the crew. A flying camel was chosen for the hat insignia, inspired by the Jewish settlement’s ‘Flying Camel Club’ and a flying camel statue erected at the 1934 Levant Fair in Tel Aviv. Registration records, logbooks, airworthiness certificates and Israeli passports were prepared to give the semblance of a civilian flight with an all-Israeli crew.

![Meteorological briefing at Ekron Air Base, 28 September 1948, prior to takeoff on the first "EL AL" flight, to pick up Chaim Weizmann in Geneva. Left to right: Yitzhak Hennenson (co-captain); Joe Segal (radio operator); ground staff member; Sy Cohen (navigator); Hal Auerbach (co-captain); Arnold Ilowite (co-captain); Abie Nathan (second officer) (in center pointing with pen); tower operator; crew member [Yehuda Shimoni?]; ground staff member; meteorologist [Fayge?]; military representative. (State of Israel Ministry of Defence, Military (I.D.F.) & Defence Establishment Archives)](http://www.israelairlinemuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/4X-ACA-Meteorological-briefing-before-Weizmann-flight.jpg)

![Some of the crew members of the Weizmann flight on steps leading to 4X-ACA at Ekron Air Base, Israel, about 26 September 1948. Left side, top to bottom: Yehuda Shimoni (navigator); Leah Melamed (assistant to Aharon Remez of the Israeli Air Force); Milt Shatan [Louis Neigle?] (flight engineer); Arnold Ilowite (co-captain). Right side, top to bottom: Yitzhak Hennenson (co-captain); Herb Bornstein (flight engineer) [Hal Auerbach?]; Leah Barbash (flight attendant); Ya’acov Feldman (Israel Defense Forces representative); Norbert Solomon (steward); Joe Segal (radio operator). The blue uniforms with gold trim were custom made for the flight by a Tel Aviv tailor. The hat insignia is a “Flying Camel”, reminiscent of the Jewish settlement's Flying Camel glider club of the 1930s and of a flying camel statue at an exposition hall in Tel Aviv. (State of Israel Ministry of Defence, Military (I.D.F.) & Defence Establishment Archives)](http://www.israelairlinemuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/4X-ACA-Weizmann-flight-crew-on-steps-of-ACA.jpg)

Fortunately, upon arrival in Geneva on 29 September 1948, the hastily contrived documentation was accepted by the Swiss authorities. Chaim Weizmann and his wife boarded the C-54 which immediately took off for the ten-hour nonstop return flight to Ekron Air Base, southeast of Tel Aviv. Approaching the Israeli coast before dawn the next day, several Spitfire fighter planes of the Israeli Air Force escorted the C-54 to Ekron. The ‘EL AL’ aircraft landed smoothly, and Weizmann’s arrival was greeted with impressive formalities, including a welcome by Government officials, a military band playing Hatikva, Israel’s national anthem, and, in the words of Munya Mardor, “an armed guard that would have been creditable at the gates of Buckingham Palace”.

The flight completed, the ‘EL AL’ C-54 was stripped of its fine furnishings and returned immediately to more mundane duty with the Air Transport Command.

First Organizational Steps

In early October 1948, following the impromptu Weizmann flight, David Remez turned his focus towards implementing the August 1948 proclamation which called for the establishment of a true national civil airline. Remez selected Dr. Avraham Ryvkind to help organize EL AL from an administrative and commercial standpoint. For the technical, operational and piloting aspects, Remez consulted with Munya Mardor, who selected Maurice Kouffman, one of the Mahal pilots. Kouffman had served as a pilot in the USAAF Air Transport Command during 1942-45 and then flew for Trans-Caribbean Airways prior to volunteering for service in Israel.

Present at the initial organizational meetings were Remez, Bar-kochba Meerovitch (deputy minister for sea and air transport within the Ministry of Transport), Aryeh (Louis) Pincus (legal adviser to the ministry), Ryvkind and Kouffman. In Kouffman’s words: “We met several nights to see the practicality of how it could be brought about, and we were very limited, not only in resources but in people. We decided it could be done, so we did it…and this was the start of EL AL”. The decision was made to use four-engine Douglas DC-4s (the commercial variant of the C-54), seek foreign landing rights as soon as possible, and formally incorporate the airline.

First Landing Rights

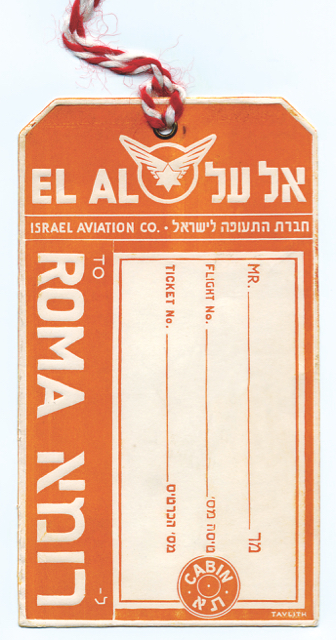

That same October, Meerovitch and Kouffman flew to Paris and met with the director of French civil aviation and the managing director of Air France, seeking landing rights for EL AL in Paris. The meetings convinced the French that Israel was capable of maintaining regular airline service, and France authorized EL AL to operate to Paris, thereby becoming the first foreign country to grant airline landing rights to Israel and El Al.

‘EL AL’ (still not yet incorporated) then made a special flight from Tel Aviv to Paris. The same C-54 of Weizmann fame was used, under the command of Captains Norman Moonitz and Gordon Levett, both of Mahal, with several high-ranking Israeli government officials aboard. On the return flight, in mid-October, the aircraft carried former US Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau to Israel on a fact-finding trip in his capacity as general chairman of the United Jewish Appeal.

Incorporation of El Al

On 15 November 1948 the new Israeli national airline was incorporated as ‘EL-AL Israel Aviation Company Limited’ (name changed on 16 May 1951 to ‘EL-AL Israel Airlines Limited’ and again on 16 May 1955 to remove the dash). The initial share capital was two million Israeli pounds (equivalent to about $60 million today), with the government holding 80% of the stock and the remainder divided among various Israeli organizations. Members of the original board of directors were E. Bavli, Z. Isersohn, H. Issachar, Munya Mardor, Bar-kochba Meerovitch, and Avraham Ruttenberg.

EL AL’s principal objective, as defined by the government, was to “secure and maintain a regular civil air link between Israel and the outside world in time of peace and war, within the framework of the maximum possible profitability”. The government also wisely accepted the basic premise urged by the company’s original directors and head officers, namely, that EL AL should be an independently run commercial entity, with its own management, based on competitive airline standards, and with policy-making decisions reserved for the board of directors representing the government.

Avraham Ryvkind became EL AL’s first employee. An immigrant from Poland, he managed EL AL while it was only a ‘paper’ airline, working as a one-man show out of an office of the Keren Hayesod organization which was engaged in obtaining funding for immigrant absorption. In effect this was EL AL’s first office. Ryvkind became a pacesetter for his successors — an idealist caught up in a tide of commerce and economic development, convinced that by working for the Israeli national carrier he was fulfilling his highest duty to his country.

On 1 January 1949 Hadassah Perlberg became El Al’s second commercial staff employee, assisting Ryvkind. Shortly thereafter EL AL obtained the first office of its own — a single room on the second floor of a building at 31 Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv. Hadassah later married Ryvkind and worked her entire career with EL AL.

Aryeh Pincus, then in his mid-thirties and a lawyer originally from South Africa, was selected from the Ministry of Transport in 1949 to become EL AL’s first managing director (a title later changed to president), with Ryvkind serving as commercial director. Considered brilliant, Pincus, like Ryvkind, had no prior airline background, but embraced his task at EL AL with messianic devotion.

In the initial months of EL AL’s formal existence, from November 1948 until February 1949, it had no aircraft of its own. In fact, EL AL was really a matter of paint. When the need arose, military transports received civilian registrations and EL AL titles. Air force personnel were handed newly printed passports and served as EL AL crews. For example, on 31 January 1949 EL AL operated a Curtiss C-46 (4X-ACG) borrowed from the Israeli Air Force, which in turn had acquired it from the Panamanian ‘airline’ LAPSA. On this special flight, Eliezer Kaplan, Israel’s finance minister, was flown on state business from Lod Airport in Tel Aviv to Rome, Corsica and Athens.

Operation Magic Carpet

Upon the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and the War of Independence, many Jewish communities in other countries of the Middle East found themselves oppressed and fearing for their safety at the hands of the governing Arabs. One of these precarious communities included a centuries-old group of Yemenite Jews living in the remote southwestern tip of the Arabian Peninsula. A simple yet tough and resilient people, they had somehow clung to their Jewish religious tradition although cut off from the main body of Jewry for over 2,000 years. They also believed, from the biblical prophecy in the book of Exodus, that some day they would be delivered from exile to the Holy Land ‘on eagles’ wings’.

With EL AL’s help, Israel and the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee mobilized to save the Yemenite Jews from destruction. Formidable obstacles were faced. The Arabs would not permit Jews to travel through the Red Sea and the Gulf of Eilat. As a result, other then an arduous ship voyage around Africa, the only way to bring the Yemenites to Israel was by air. Aviation fuel was so scarce in Israel that all was needed for the war effort; none could be spared for an airlift. Moreover, the British who controlled Aden, the only place where the Yemenites could be assembled for transport to Israel, would not make fuel available. To make matters worse, Israeli aircraft were not permitted to overfly Arab airspace en route to and from Aden.

To overcome these problems, EL AL, in a program organized by Yoel Palgi, cooperated with a charter operation established by the Joint Distribution Committee and by the adventurous James Wooten of Alaska Airlines. In January 1949, airplanes in the markings of Alaska Airlines, and later Near East Air Transport (formed especially to carry immigrants) and some with Cia. Cubana de Aviacion ‘CU’ registration numbers on the tail, began flying to Aden to airlift Yemenite Jews in Operation Magic Carpet.

Fuel supplies were finally located, but only in remote Asmara, Ethiopia, so the flights had to ply a triangular route of some 2,600km (1,600mi): from Lod Airport (Israel) southwest to Asmara for fuel; then east to Aden to pick up the Yemenites; and then back the same way to Israel.

The airlift relied on Curtiss C-46s and Douglas C-54/DC-4s, many of which came from Israeli sources, including EL AL. When flown on the airlift, the EL AL aircraft were repainted with the markings of the charter airlines. EL AL also loaned pilots and cabin crew for the operation.

A DC-4 normally seated about 50 passengers. However, the Yemenites were thin, and five persons usually could fit into seats designed for four. So the normal seats were removed, and wooden benches installed with seat belts across them, to hold more passengers. As Capt. Sam Lewis related, “When a ‘plane was loaded, a crew member would stand at the top of the stairway sizing up the passengers and, when necessary to crowd more on a bench, would yell ‘give me a thin one'”. This unusual arrangement was euphemistically called ‘special immigrant high-density seating’. Thus, each DC-4 took off with about 120 people packed inside.

The Yemenites had never seen a plane before, so one can imagine their numb astonishment at seeing this great bird and wondering how it flew. Once inside the aircraft they usually sat stoically and in awe. But the flights had their unusual moments. Once a pilot passed back to the cabin a request for some water. Soon a Yemenite youngster brought to the cockpit a cup of freshly boiled tea. This jolted the crew because they knew there were no facilities for boiling water on the plane. Hastening back to the passenger cabin, they were astonished to see the Yemenites firing a makeshift stove on the floor, heating a kettle of water for tea!

At the peak of Operation Magic Carpet, aircraft flew constantly to Israel, seven to eight flights a day, over a route that took about nine hours. They had to fly a narrow corridor along the middle of the Red Sea and Gulf of Eilat to skirt Arab countries, with instruments of dubious accuracy and deprived of radio guidance. Engines suffered from desert sand and dust, and a forced landing anywhere would have meant disaster, but remarkably no mishaps occurred.

Upon arrival in Israel, the Yemenites believed their prayers had been answered. Many kneeled and kissed the tarmac upon arrival. Truly they had realized their dream — being carried to the Promised Land ‘on eagles’ wings’. By the time the airlift ended in September 1950, 47,000 — almost all of Yemen’s Jewish population — had been carried to Israel, together with some 3,000 Habbanim Jews who had resided in another remote area of the South Arabian peninsula.

Operation Ali Baba (Operation Ezra and Nechemiah)

The flights from Yemen were followed by an even more massive airlift of Jews from Iraq, called Operation Ali Baba. In March 1950, following persecution of the local Jewish communities, the Iraqi government allowed Jewish emigration, on condition that Jewish property be abandoned in favor of the government. Moreover, the airlift was allowed only without direct flights between Iraq and Israel. All flights had to land first in neutral Cyprus. On that basis, Operation Ali Baba started the following May. By its end in December 1951, 113,000 Iraqi Jews had been flown to Israel, with EL AL playing a major role in the rescue.

Meanwhile, EL AL also started special immigrant flights from Europe and many other areas, including India. These airlifts were often charged with emotion. In the words of early EL AL stewardess Livia Eisen Chertoff, “many passengers would kiss the uniforms of the crew members upon seeing the Jewish Star of David insignia”. EL AL became the first visible symbol of a new life in a reborn land.

EL AL’s First Aircraft Purchases

At the beginning of 1949 EL AL’s plan to have its own fleet of DC-4s became a reality. A reliable four-engine transport that had proved itself during the Second World War, the DC-4 could cruise at 450km/h an hour (280mph) at up to 4,300m (14,000ft), and had a range of 4,000km (2,500mi). But it was not pressurized. This prevented it from flying at higher altitudes to avoid rough air and bad weather. By 1949 most of the world’s major airlines were flying pressurized aircraft, such as the Lockheed Constellation, Douglas DC-6, and Boeing 377 Stratocruiser. Given Israel’s austerity economy at the time, the best EL AL could do was to acquire second-hand DC-4s. Nevertheless, the DC-4s were tried and true aircraft, and their range was ideal for EL AL’s projected services to Europe.

With funding from the government, the Jewish Agency and other Jewish organizations such as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), EL AL purchased in February and March 1949 the first aircraft of its own — two DC-4s from American Airlines. Capt. Maurice Kouffman personally took delivery of 4X-ACD and 4X-ACC at Tulsa, Oklahoma, on 26 February and 15 March 1949 respectively and flew each to Idlewild Airport, New York (now JFK International Airport), for overhaul by the Willis-Rose aircraft company.

Meanwhile, the United States arms embargo continued. No aircraft could be exported from the US without an export license from the Department of Commerce. However, following negotiations between the Israeli and US governments, on 1 March 1949 the State Department announced that export licenses would be granted for the DC-4s.

On 29 March 1949, export license in hand, EL AL unveiled 4X-ACC at Idlewild, painted in the first official livery of EL AL and named ‘Rechovoth’, in honor of the town of Chaim Weizmann’s residence in Israel. A flying six-pointed Star of David, EL AL’s first official symbol, graced the window line aft of the cockpit. That afternoon, 4X-ACC took off on EL AL’s first trans-Atlantic flight, a survey trip to Tel Aviv via Gander, Shannon and Paris. Its seven-person crew included Capt. Kouffman, Capt. Martin Ribakoff (also formerly with Mahal), Capt. John Greenacre of Pan American, other Pan Am cockpit crew, and Kouffman’s wife, Marilyn, as stewardess. On 3 April 1949, to the joy of the handful of EL AL staff in Israel, 4X-ACC landed at Lod Airport — the first aircraft owned by EL AL to touch down in Israel.

After six days at Lod, the DC-4 was flown back to the US by Kouffman, this time with Aryeh Pincus on board, for the purpose of obtaining US landing rights for EL AL. Following two weeks of negotiations in Washington, DC, EL AL received the coveted authorization to operate passenger aircraft to New York. Soon thereafter, representatives of EL AL in New York interviewed and hired additional pilots and technical personnel with aviation experience to bolster EL AL’s staff in Israel and to prepare for the initial flights to New York.

During 29 May to 31 May 1949, Kouffman flew sistership 4X-ACD on a public relations tour in the U.S., from New York Idlewild Airport to Indianapolis and Oklahoma City and back to Idlewild. Thereafter, 4X-ACD was flown to Israel where EL AL personnel prepared it for the start of regular passenger service.

First Scheduled Service

With two DC-4s delivered and one of them at Lod, on 14 July 1949 EL AL received an Israeli ‘Certificate to Commence Business’ as a scheduled airline.

Two weeks later, on 31 July 1949, EL AL initiated scheduled service to Paris (via a fuel stop in Rome), with DC-4 4X-ACD. This first flight began at the office of Bernard Wajnberg, director of Globe Travel Service on Har Sinai Street in Tel Aviv. Wajnberg was considered Israel’s most knowledgeable travel agent of his day, having started in the business in his native Poland in the early 1930s. From EL AL’s infancy he placed his professional advice and skill at the disposal of the new airline. Wajnberg booked 24 passengers who assembled at his office for baggage weigh-in and to take a chartered bus to Lod. Following a welcome at the airport by EL AL’s first station manager, Francie Oberlander, and a greeting by a hastily trained but enthusiastic cabin crew, the passengers enjoyed a smooth journey to Paris. EL AL was a true international scheduled airline at last. No matter that it operated only one roundtrip service a week.

The Second DC-4 Joins Flight Operations in Israel

While 4X-ACD had the honor of inaugurating scheduled service, EL AL’s other DC-4, 4X-ACC, was still in the US being checked out at the Douglas Aircraft plant in Santa Monica, California to confirm its airworthiness for regular passenger service. Finally, in late August 1949 4X-ACC was flown to Israel to join the El Al ‘fleet’. With two operating DC-4s EL AL expanded Paris service to two flights a week.

EL AL undertook one of its most emotional flights on 16-17 August 1949. Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, had died in Vienna, and the Israelis wanted to bring him home, to the land of his dreams, for reburial. Using DC-4 4X-ACD, already named ‘Herzl’, EL AL flew to Tulln Air Force Base near Vienna and carried Herzl’s remains to Israel, where he is now buried on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem.

By October, heavy bookings on EL AL’s flights to Paris, as well as special flights to Rome, caused EL AL to charter Douglas DC-3s from Universal Airways, a small airline run by Jewish interests in South Africa and which primarily operated between Johannesburg and Tel Aviv.

On 18 December EL AL added scheduled service to Rome and Zurich (again first operated by 4X-ACD), and on 22 December its fourth destination, London (via Rome, with 4X-ACC). The number of all EL AL flights per week from Tel Aviv was now three: one to Rome and Paris, one to Rome and Zürich, and the third to Paris and London. Accordingly, the monthly passenger count rose from 400 to 750.

Arkia Is Born

Israel’s first local domestic airline, named Arkia, was founded in late 1949, owned 50% by EL AL and the balance by the Israeli Histadrut Labor Organization. This affiliation with EL AL continued until 1980, when all of Arkia was sold to privately owned Kanaf and employees.

The original name of the new airline was ‘Eilata’, meaning ‘to Eilat’. However, as Transport Minister David Remez preferred names drawn from the Bible, it was changed in September 1950 to ‘Arkia’, which translates as ‘I will soar’ or more specifically as ‘I will go up to the rakia’ – the Biblical Hebrew word ‘rakia’ meaning a special portion of the sky high above, or the canopy of heaven. Thus both EL AL and Arkia are Hebrew expressions that loosely translate as ‘to the skies’.

Arkia’s first goal was to open air service to Eilat, then a remote pioneer town at Israel’s southern tip on the Gulf of Eilat leading to the Red Sea. This took awhile because, at first, Arkia had no aircraft and Eilat lacked a suitable landing strip. At the beginning of 1950, however, a reasonabl runway paved out of rock and sand, and a primitive terminal, were built.

Using a two-engined Curtiss C-46 (4X-ACT) received from EL AL, with an EL AL crew under the command of Zvi Tohar, Arkia’s official inaugural flight from Tel Aviv to Eilat took place on 28 February 1950. This C-46, together with two smaller de Havilland Dragon Rapide aircraft obtained from the Israeli Air Force, initially comprised Arkia’s entire ‘fleet. Flight time between Tel Aviv and Eilat was typically a little over one hour, whereas a road journey was impractical because only a primitive, often impassable, dirt road to Eilat existed at the time. Soon Arkia was bringing in food, water and machinery to Eilat’s settlers and constructions workers. It also delivered all newspapers and mail, and was the only practical means of evacuating the sick to Tel Aviv. Arkia’s activities thereby became the center of social life in Eilat. Flight frequency soon rose to at least two per week.

From this modest beginning, Arkia, while affiliated with El Al, later expanded to serve many destinations within the entire length of the country. Eilat developed into a major tourist resort with luxury hotels and inviting water sports, and Arkia added successive types of more modern aircraft to serve the rising demand.

El Al’s First Cargo Operatiohree

On 24 January 1950, a month before Arkia’s inaugural flight, El Al acquired three Curtiss C-46s (4X-ACE, -ACF and -ACT). Each had been employed as a transport aircraft during the 1948 War of Independence following their arrival from the US and Panama via Al Schwimmer’s Panamanian ‘airline’, LAPSA.

The C-46 was a twin-engine, medium-range transport designed at the end of the 1930s, which earned fame as the prime mover of supplies over the Himalayas, ‘The Hump’ run between India and China during World War II. Available in large quantities after the conflict, many found their way to airlines around the world for use as cargo carriers, and others were converted to passenger use. The C-46 could cruise at 280km/h (175mph) at 3,000 meters (10,000ft), and had a range of 5,000km (3,100mi), with a usual crew of four. Compared to the legendary Douglas C-47 (DC-3), the C-46 had a more rotund fuselage that could accommodate up to 6,750kg (15,000lb) of cargo.

EL AL used two of the C-46s to launch a freight operation on 26 January 1950 between Israel and several European cities. With foresight it recognized the potential value of air cargo, as well as the importance of air transport to the future of Israeli exports of flowers, fresh produce, and other goods. In April 1951 EL AL established one of the few regular cargo runs to London; intermediate stops were made as required. By 1955 the usual route to London was via Athens, Rome, Düsseldorf and Amsterdam, with the return to Tel Aviv via Brussels, Rome and Athens. Schedules were arranged to permit other ports of call. Another regular freight service was established to Paris.

Between 1950 and 1955 EL AL operated seven ex-Israeli Air Force C-46s, but not all at the same time. Besides carrying freight, some of EL AL’s C-46s were employed in passenger service, usually fitted with 38 seats, and they supplemented the DC-4s (and later the Lockheed Constellations) on shorter or less-traveled routes.

First Casualty

By the start of February 1950 EL AL’s scheduled flights to Europe were running smoothly with the two DC-4s. This promising state of affairs, however, was soon shattered. On the night of 5-6 February, in a rare freezing winter storm, snow started falling in Tel Aviv. The DC-4 Herzl (4X-ACD) was at Lod, being prepared for a flight to Paris. As ice accumulated on the wings and airframe, maintenance personnel removed it.

Several notables were on board, including Aryeh Pincus, EL AL’s president, Bar-kochba Meerovitch of the Ministry of Transport, and Hayman Schechtman (Shamir), the deputy commander of the Israeli Air Force. Abba Eban, Israel’s representative to the United Nations at the time, and Golda Meir, later Israel’s prime minister, were scheduled to be on the flight, but the weather turned them back enroute to the airport.

At about one in the morning, Capt. Kenneth Fuller, made the decision to take off. Gaining speed on the runway, the DC-4 lifted off slightly, but immediately lost height and careened off the side of the runway. All aboard managed to escape, aided by passenger Eddy Kaplansky, a former Mahal pilot, who quickly opened emergency exits. Flames soon engulfed the aircraft, however, reducing it to smoldering ruins — and this was one-half of EL AL’s total passenger fleet. The mail was saved, but the only surviving cargo was a consignment of diamonds of which only some were recovered after a spirited search — which did not lack for volunteers. According to Kaplansky, the cause of the crash was a runaway propeller of one of the engines, which resulted in loss of power and — considering the weather, wet runway and likely accumulating ice — made liftoff impossible.

More Acquisitions and Routes

EL AL moved quickly to close the gap caused by the loss of the DC-4 and also to implement plans for an expansion of service in summer 1950. At first, a replacement DC-4 was leased briefly from the affiliated immigrant airlift charter operation of Near East Air Transport. Then three additional used DC-4s were purchased, two (4X-ADB and 4X-ADC) previously with United Air Lines, and one (4X-ADN) from Trans-Caribbean Airways. Apparently EL AL liked United’s color scheme of dark blue and silver, because EL AL retained the livery and repainted its other DC-4s to match.

With the increase of its DC-4 fleet to four aircraft, and the availability of its two C-46s, EL AL was able to substantially expand its network and frequency of service.

To the United States

El Al’s main objective was to launch service to the USA. For this purpose EL AL opened offices in New York, at 250 West 57th Street in Manhattan and at Idlewild Airport. Israelis Yehuda Koppel and Dror Galezer arrived to run the city office, and were assisted by locally hired Joyce Perlman Baron, previously with Trans-Caribbean Airways. Additional crew and maintenance technicians were hired at Idlewild, led by Capt. R. C. Waring, EL AL’s Chief of Flight Operations.

On 18 June 1950, only five days after Israel signed a bilateral air agreement with the US, EL AL inaugurated trans-Atlantic service with a charter group organized by the Israeli youth organization, Habonim. The route was via Rome, Paris, Shannon, and Gander (Newfoundland), and employed a combination of two of the newly acquired DC-4s (4X-ADB and 4X-ADC), one aircraft flying between Israel and Europe and the other assigned to the trans-Atlantic stage. The return flight was made with a group charter organized by Pioneer Women, arriving at Tel Aviv on 25 June.

Also on 25 June, EL AL launched its second (but first ‘official’) round-trip passenger flight between Israel and the US. With a charter group of passengers and the same combination of DC-4s, the flight stopped at Rome, Shannon and Gander, arriving at Idlewild in New York, on 27 June 1950. This marked the start of weekly DC-4 charter service by EL AL between Israel and New York.

To South Africa

In fall 1950 EL AL acquired Universal Airways, a South African company. Universal had been flying to Lod as part of a Johannesburg to London route, incongruously using short-haul Douglas DC-3s. Established by Herbert Cranko, a South African Jew, and by other South African Zionists, Universal contributed to the War of Independence by flying in needed supplies and equipment and providing another link to the outside world. Cranko left his post as managing director of Universal to become EL AL’s director of administration and finance. EL AL immediately replaced the DC-3s with DC-4s, beginning service on 29 October 1950 to Johannesburg (Palmietfontein Airport), via Khartoum, Sudan; Nairobi, Kenya; and Livingstone, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia).

To Additional European Cities

EL AL also expanded its European destinations during 1950-51, adding Vienna, Istanbul, Athens and Nicosia. In preparing for the first scheduled flight to Istanbul, 1 March 1951, EL AL found itself short of aircraft, and it quickly improvised by borrowing one of the Israel Air Force’s C-47 Dakotas (a military version of the DC-3). This was one of the few times that EL AL operated this venerable type of twin-engine aircraft. Following this flurry of route expansion, EL AL maintained this route network for another five years.

EL AL’s first anniversary of scheduled flight operations was celebrated on 31 July 1950. During this first year EL AL had flown 172 roundtrips covering 1,180,000km (732,000mi), carrying 10,405 passengers and 66,225kg (146,000lb) of freight. The number of EL AL employees reached 350, some 75 of whom, including 45 flight crew, were non-Israeli. This ratio would inevitably change as native Israelis acquired the necessary experience to take over as pilots and technicians.

The DC-4’s Swan Song

The end of 1950 marked the height of DC-4 activity for EL AL. In addition to the new Johannesburg service, there were eight weekly flights to Europe: three to Rome; two to Paris; two to London; and one to Istanbul, Vienna and Zurich. EL AL knew, however, that the days of its ‘Fours’ were numbered. All its competitors were already operating pressurized and larger aircraft. EL AL could not exist forever on immigrant airlifts and loyal Zionistically motivated air travelers. Already three used Lockheed Constellations had been purchased by EL AL and, following overhaul by Al Schwimmer’s group in Burbank, California, the first arrived in Israel on 22 December 1950.

As the Constellations entered service in 1951, EL AL sold its DC-4s, although one aircraft was lost on 24 November 1951 in another accident. On a freight run from Tel Aviv to Amsterdam via Rome and Zurich, a route ordinarily plied by a C-46, EL AL substituted a DC-4 (4X-ADB) with its seats removed. On approach to Zurich’s Kloten Airport, the aircraft clipped some trees on a wooded hillside and crashed, killing six of the crew of seven, including Capt. Theodor (Ted) Gibson of Miami, one of the first foreign volunteers for the Israeli Air Force. Gibson was a former US Navy dive-bomber pilot and at the time was the chief instructor of the advanced flying school in Israel. EL AL’s commercial director, Avraham Ryvkind, had been on the ill-fated flight, but suffering exhaustion from overwork, he deplaned at Rome for a rest and was spared.

By the end of 1951 only two DC-4s (4X-ACC and 4X-ADC) remained in EL AL’s fleet. They were sold in January and April 1952 respectively, thus ending EL AL’s pioneering and emotional era with the classic Douglas airliner.

Last updated 15 January 2023

Copyright 2011-2023, Marvin G. Goldman