“I will give you the land of Israel” (Yehezkiel 11:17)

Relaxing in your modern and comfortable seat onboard EL AL’s Boeing 787 Dreamliner, you notice that the aircraft’s ‘mood lighting’ has automatically adjusted to the time of day, and now you look out and see the sparkling sunshine on the Mediterranean Sea below and the coast of Israel drawing near. You have been enjoying EL AL’s latest in-flight entertainment system, computer connections, and fine meals and service. But now it’s time to land—in a very special land. Soon Tel Aviv’s seaside promenade and hotel row appear in view, and in a few more minutes you will be landing at Ben-Gurion Airport. The aircraft’s wing flaps deploy, producing a rushing sound, and the landing gear lowers with a thunk, as the airplane crosses the shoreline and continues its smooth glide over Tel Aviv. Whether you are returning home, or whether it’s your first trip to Israel or one of many, your heart beats with emotion. The airport fills the horizon. The aircraft eases down, the wheels kiss the runway—you are in the Holy Land.

* * *

A mere vision in 1948, EL AL today is one of the world’s most advanced and efficient airlines and a true success story of international commercial air transport. The birth and rise of EL AL are directly linked to the dramatic events shaping the State of Israel. EL AL Israel Airlines emerged from the same desperate struggle that established Israel as a renewed homeland and sanctuary for the Jewish people. Upon Israel’s declaration of independence on 14 May 1948, the new country was immediately attacked by the combined armed forces of its surrounding Arab neighbors. Israel’s only outlet to distant allies was to the West, over the Mediterranean Sea, and this route could be swiftly accessed only by air. Foreign air carriers could not be relied on to meet Israel’s vital needs during hostilities. EL AL was thus created as the ‘chosen instrument’ of the state to be its civil aviation lifeline.

Miraculously, Israel’s ground and air defense forces and the determination of its people repulsed the invading armies and preserved the freedom of the fledgling state. The way was thus cleared for EL AL to develop as Israel’s principal airline. The path to development, however, started from almost nothing. EL AL had almost no money, no experienced executives, and little in the way of suitable aircraft or trained technical personnel. To fully appreciate the meager resources—and the imposing challenges—facing El Al at its creation, we must begin with a flashback to the struggle for the birth of the State of Israel and the crucial role of aviation.

Israel as a Jewish Homeland

The Jewish people have regarded the land of Israel as their legitimate homeland from time immemorial, promised to their Patriarchs and descendants in the Bible. For over 1,200 years until the year 70 CE (with only a brief interruption) a Jewish state existed in the Holy Land, with its spiritual seat at the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. That year witnessed the destruction of the Jewish state by the Romans, and thereafter the land suffered a wave of conquests by foreign interests over the centuries. The vast majority of Jews were scattered among other nations. Yet they were joined in keeping the Jewish faith alive by thousands of their brethren who continued to live in the land of Israel during this entire period. Over these centuries the yearning for an ingathering of the Jewish people to Jerusalem and the land of Israel was repeated daily by devout Jews in their traditional prayers.

Palestine (as Israel was then called) was an impoverished backwater of the crumbling Ottoman Empire, an insignificant part of Turkish-controlled Arab lands in the Middle East at the end of the 19th century. From the 1880s until the start of World War I in 1914 many eastern European Jews, faced with continued persecution in their countries, began to transform into reality their dreams of returning to the Jewish homeland. Several waves of Jewish immigrants returned to Palestine and settled into a harsh pioneering existence in the Holy Land.

By the end of the war in 1918, the British and French had ousted the Turks from the Arab lands in the Middle East. Palestine, with its mixed population of Jews and Arabs, and amounting to only about 1% of the area of these Arab lands, was handed over to the victorious British under a League of Nations Mandate.

In carrying out the mandate, the British tried to practice a balancing act between the Jewish and Arab populations in Palestine. Already, Britain’s Balfour Declaration of November 1917 had acknowledged the right of the Jews to have a homeland of their own in the area of Palestine. Jewish immigration resumed after the war, and Jewish interests purchased and developed increasing areas of land. The Arabs, however, pressed the British in the opposite direction and also applied physical pressure on Jewish settlements in the Holy Land, culminating in a series of riots against the Jews during the 1920s and 1930s. For political reasons the British tended to side with Arab demands. Immigration of Jews to Palestine became subject to strict limits, and by the start of World War II in 1939 the British banned such immigration completely. Against this dual background in Palestine between the two world wars—that is, the politics of the British Mandate government and the rise of civil strife between the Jewish and Arab populations, civil aviation was born in the Holy Land.

Civil Aviation Under the British Mandate

Coinciding with the end of World War I in 1918, when the British assumed control of Palestine, surplus military aircraft became readily available and were converted to civilian use. This led to the establishment in the early 1920s of the world’s first sustained airline operations.

The first airfields in Palestine had been built by the Turks (with German assistance) in 1917 for military use. These were mostly primitive landing strips, with the more important ones located at Tzemakh (Samakh) at the south shore of the Sea of Galilee (near Tiberias in the north), Ramle in the center (southeast of Tel Aviv) which became the British Royal Air Force (RAF) headquarters for Palestine and Transjordan, and Gaza on the southwest coast.

Imperial Airways

Quite naturally, the British, as the governing authority at the time, initiated the first airline service to Palestine. In 1924 the British government consolidated four independent companies into Imperial Airways, a ‘chosen instrument’ whose primary purpose was to connect London with the Empire. The first scheduled airline route to Palestine was established in January 1927, when Imperial’s tri-motor de Havilland D.H.66 Hercules land planes stopped at Gaza, en route between Cairo and Iraq (Rutbah Wells, Baghdad and Basra) as part of the new Cairo-Karachi route. Imperial began an England to India service at the end of March 1929, and D.H.66s night-stopped at Gaza en route between Alexandria and Karachi.

In October 1931, Imperial separated its India and African services. The result was that four-engine Short S.17 Kent Scipio class flying boats opened a route from Athens to Haifa Bay, via Castelrosso (then under Italian control), and on to Tiberias, alighting on the Sea of Galilee. At 210 meters (700ft) below sea level, this was probably the lowest level at which any aircraft was then operated. Passengers were then taken by car to nearby Tzemakh and continued their journey with four-engine Handley Page H.P.42 Hannibal class biplanes to Baghdad and Karachi. At the same time, a connecting service was added between Alexandria and Haifa, which was subsequently switched to Tiberias.

By December 1934 the Kent flying boats were scheduled from Athens to Alexandria and Cairo, with H.P.42 land planes taking over to Baghdad and Karachi, with a stop in Gaza. Service via Tiberias resumed in October 1937, with the introduction of the larger Short S.23 C class flying boats on the route to India.

The Birth of Jewish Civil Aviation: Gliders and Flying Camels

Aviation by Jewish residents in the Holy Land remained only a dream in the 1920s. The two earliest visionaries were Yisrael Shochet and Tzvi Nadav. Both foresaw the importance of aviation, not only as a commercial venture but also as a means to link and protect the Jewish settlements in Palestine. Shochet tried in the 1920s to form an aviation school and modest air service within Palestine. However, the British refused permission for such a venture, and in any event he lacked sufficient financial and other resources. Nadav, on the other hand, recognized that the Jews could probably become involved in aviation by learning to fly gliders, since the British would permit this as a ‘sporting’ activity. In 1927 Nadav traveled to Paris to study aeronautics and gliding, with a view to implementing his idea upon his return.

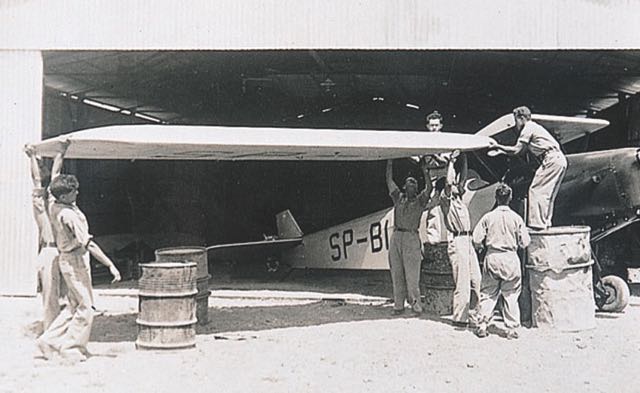

Early in the 1930s, an increased flow of Jewish immigrants from Europe to Palestine included several who had been active in aviation in Germany and Poland. However, outlets for aviation-related activity in Palestine were still almost nonexistent, and there was no access whatsoever to motorized aircraft. In March 1933 these early Jewish aviation enthusiasts, led by Shochet and Nadav, established the first aviation club in Palestine, called the ‘Flying Camel Club’.

The club promoted aeronautical studies, aircraft modeling and the flying of gliders. It especially attempted to interest Jewish youth, and had hopes of acquiring motorized aircraft. The name soon changed to the Aero Club of Israel, although, as we shall see, the flying camel symbol emerged anew as the crew emblem for Israel’s first international airline flight after independence in 1948. The Aero Club of Israel remains active today and has introduced thousands of young Israelis to the joys of aviation.

In April 1935 the Second Maccabiah (Jewish Olympic Games) was held in Tel Aviv. By a stroke of good fortune, it included flying competitions, and a group of Jewish fliers arrived from Germany with two German-built Schneider Grunau Baby gliders. One of the participants, Ernst Rappaport, was a fine track and field athlete and, most importantly for Israeli civil aviation, one of the best glider pilots in Germany. After the Maccabiah Games the Germans left their gliders in Palestine and several settled there, including Rappaport, who became the principal instructor. One of his initial pupils, Yitzhak Hennenson, later rose to become a captain with El Al. Another early glider pilot, Uri Breier, became, in August 1952, the first native Israeli to captain an El Al aircraft on international flights. Training courses in gliding started in 1935 at Mount Carmel in Haifa, and activity soon spread to other locations. Two Polish primary trainers, a Czajka and a Wrona, were also added. During 1937-39 the principal courses were held at Givat Hamoreh, near Kfar Yeladim in the Jezreel Valley. Dozens of enthusiasts thus received their introduction to flying on gliders.

“Our Own Very First Airplane”

Simultaneous with the formation of the Flying Camel Club, another Jewish settler in Palestine, Yitzhak Chizik, set out to transform the dream of powered aircraft into reality. He traveled to England to study aviation and returned to Palestine in 1934 holding a commercial pilot’s license. Meeting with two key figures, David Ben-Gurion and Dov Hoz, he urged the purchase of an aircraft and the establishment of a school of Jewish aviation. Ben-Gurion was a political leader who later became Israel’s first prime minister, and Israel’s main international airport is now named after him. Dov Hoz was another advocate of Jewish aviation, and the north Tel Aviv airport in Israel is now named Sde Dov or Dov Field in his memory. Chizik received expressions of support from both men and managed to scrape up enough money from national Jewish institutions in Palestine to purchase the first powered airplane for Jewish aviation in the Holy Land. It was a new single-engine de Havilland D.H.82A Tiger Moth acquired by Chizik and Dov Hoz in England in September 1934. That fall, David Ben-Gurion whispered to a gathering in Warsaw of Jewish leaders supporting increased immigration to Palestine, “we even have our own very first airplane.”

Aviron

On 21 July 1936, the first Jewish civil aviation company was formed in Palestine, called Aviron, which in Hebrew means ‘airplane’. Aviron was established by various Jewish national institutions in Palestine, including the Histadrut Federation of Labor and the Jewish Agency. Behind the scenes it was also supported by the Haganah, the group dedicated to the defense of the Jewish community in Palestine and the precursor of the present-day Israel Defense Forces. Aviron’s stated goals were to conduct a flying school for Jewish aviators and to develop internal commercial flights between Tel Aviv and Haifa and the Jordan Valley. There was a third goal—to serve the Haganah in reconnaissance and defense missions-—but this had to be carried out in secret. Such activities were discouraged by the British authorities who viewed them as a threat to the balance of forces between the Arab and Jewish communities.

Aviron’s flying school started in Afiqim near the Sea of Galilee, in March 1938, with the sole Tiger Moth and two Polish-built aircraft, a two-seat RWD 8 and a three-seat RWD 13. By early 1940 Aviron owned nine aircraft, all single-engine: two RWD 8s, two RWD 13s, a five-seat RWD 15, three US-built Taylorcrafts, and one British Miles M.3A Falcon Major. These were mainly used as trainers, but they also served Jewish national interests by acting as spotters to protect groups of workers engaged in road and building construction in remote locations, and by dropping essential supplies of ammunition and food to those living in new outposts, especially during the harsh winter periods.

Other Aviron activities included the purchase, sale, and repair of light aircraft. Moreover, the company flew some charter flights within Palestine and eventually operated regular service to Tiberias, until war curtailed all activity in 1942.

Palestine Flying Service

Another Jewish flying school, called the Palestine Flying Service, opened in 1937 at Lydda Airport with the open approval of the British Mandate authorities. This enterprise was the brainchild of an American Jew, Moshe Chaim Katz, who teamed up with Edwin (Leibowitz) Lyons, an American who arrived in Palestine in a Taylorcraft, fleeing from Spain where he had flown for the Spanish Republican forces, and Avraham Schechterman, a leader of the Jewish underground movement called Etzel. Training was given on three Taylorcrafts and other single-engine aircraft, and instruction encompassed aeronautical theory and aircraft repair.

The first class graduated on 21 April 1939 in an impressive gathering at Lydda, presided by British High Commissioner Harold McMichael. The graduates were the first Jews to receive pilot licenses in the Holy Land.

Like Aviron, the Palestine Flying Service also had a secret mission—to train Jewish residents in aviation skills for defense purposes. However, whereas Aviron conducted its training in the relatively remote Jezreel Valley, remarkably the Palestine Flying Service operated under the very nose of the British Mandate authorities. Nevertheless, the advent of World War II brought the courses of the Palestine Flying Service to a close.

Airport Development Under the British

Meanwhile, the British started to build additional airfields in Palestine. In 1934 they opened a small airport at Haifa, originally to serve the Iraq Petroleum Company, and paved another in 1938 in northern Tel Aviv, the present Sde Dov or Dov Field.

The main development by far, however, was the British decision to construct a major international airport at Lydda, sited near the junction of the railways running east to Jerusalem, north to Syria and south to Egypt. (Renamed Lod by the Israelis, this is today Israel’s main airport, Ben-Gurion). An airstrip at Lydda, with two unpaved runways, had been constructed in 1934, largely at the urging of Airwork, a British company involved with the Egyptian airline Misr Airwork (Misrair). Politics motivated the British, as they envisioned Lydda as an alternative international center for Middle East operations and routes to the East if they were forced out of neighboring Egypt.

Work began in 1935, and Misrair started regular service to Lydda from Cairo on 3 August that year, using a de Havilland D.H.86 on its route to Nicosia, Cyprus. Subsequently, Misrair flew via Lydda to Haifa and Baghdad.

By April 1937 Lydda boasted four fully operational concrete runways of about 800 meters (2,600ft) each, two of which were soon extended to 1,200 meters (3,900ft). Progress was slowed when Arabs set fire to the buildings, but a remarkably modern passenger terminal building of three stories, topped by a glass-enclosed control tower, was eventually completed to make Lydda the finest airport at the time in the Middle East.

Several airlines introduced regular scheduled service to Lydda. The first continental European airline was LOT of Poland, which began service on 4 April 1937 from Warsaw using Douglas DC-2s, and later Lockheed 14 aircraft. The following year, this route was operated in pool with LARES of Romania. Holland’s KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, which had stopped at Gaza on its Amsterdam to Batavia (Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia) route since 1931, moved to Lydda.

Imperial Airways used Lydda to refuel Handley-Page HP42 Hannibal class and Armstrong Whitworth XV Atalanta class airliners offering an England–India service. To service them, in 1937 Imperial built a large hangar that is still in use today by EL AL for some of its Boeing jets.

Meanwhile, Imperial (which became British Overseas Airways Corporation in April 1940) continued regular flying boat service to the Sea of Galilee until April 1942 when, following an accident in stormy weather, it shifted marine operations to Kallia on the Dead Sea. At 393 meters (1,292ft) below sea level, Kallia continued in use as a BOAC base until January 1947.

Another flying boat operator to Palestine was Ala Littoria of Italy, which in April 1937 began service from Trieste and Brindisi to Haifa, via Athens, with its unusual three-engine twin-hulled Savoia Marchetti S.66s.

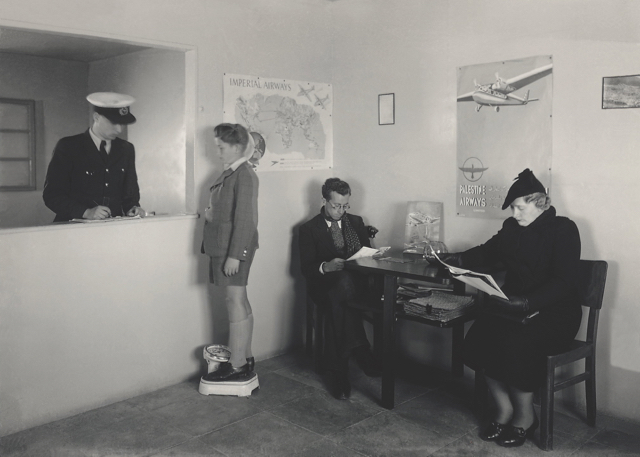

Land of Israel Airways (Palestine Airways)

The British, Jewish, and international aviation activity in Palestine was joined by yet another entrant. On 18 December 1934, the first purely commercial airline based in Palestine had been registered by Pinchas Ruttenberg, the Jewish head of the electric company in Palestine, with funds from Jewish and British sources. Ruttenberg’s approach differed from that of Chizik, Ben-Gurion, and other Jewish pioneers. By emphasizing the commercial aspect, including an affiliation with Imperial Airways for crews and technical assistance, and by deferring the goal of Jewish aviator training and aviation defense as pursued by Aviron, Ruttenberg obtained British permission to form Palestine Airways Ltd, whose name in Hebrew was Land of Israel Airways Ltd.

Palestine Airways started with two six-passenger Short S.16 Scions, powered by two Pobjoy engines. These were the first aircraft registered in the Holy Land.

On 11 August 1937, Palestine Airways (now officially registered as Palestine Air Transport) began thrice-weekly service between Lydda and Haifa. Soon thereafter it moved operations to the newly constructed north Tel Aviv airfield, and in September 1938 service was extended to Beirut, Lebanon, marking the first international route of a local airline, with Haifa flights boosted to daily frequency.

By the end of 1938 the airline had acquired two larger aircraft—an eight-seat de Havilland D.H.89A Dragon Rapide and a ten-seat Short S.22 Scion Senior—with which to add service to Larnaca, Cyprus, and charter flights to Egypt. The Short S.22 proved to be the only four-engine aircraft on the British Mandate Palestine register.

The Impact of World War II

The outbreak of war in September 1939 dashed the hopes of two other recently formed Palestinian air transport companies. Tel Aviv-based Hevra Avirit Miskharit (Commercial Aviation) transported fresh fish from Aqaba, on the Red Sea, with a Fokker F.XVIII tri-motor acquired from ČLS of Czechoslovakia. Kanfei Hamizrah (Orient Aviation Co) acquired three RWD light aircraft for instruction, air taxi, and charter work, and intended to manage landing grounds as well as operate an air freight service to Cyprus and Transjordan.

Lydda Airport’s rising international position was also shattered. Imperial/BOAC continued operations to Palestine until the fall of France in June 1940, and sustained flights to Lydda were not revived until 1944. (Flying boat service continued via Palestine on the ‘Horseshoe Route’ between South Africa and the Far East.) When the Japanese military advanced into Burma and Malaya in February 1942, Holland’s KLM curtailed its route to Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia) and made Lydda the eastern terminus of its route to Asia. Egypt’s Misrair, which had suspended flights upon the British declaration of war, resumed a weekly service in May 1940 between Cairo and Cyprus, via Lydda and Beirut. The Scions of Palestine Airways were impressed in August 1940 by England’s Royal Air Froce for use as transport and communications aircraft, and the company was never revived as an airline. The Palestine Flying Service school closed, and its light aircraft were acquired by Aviron. While Aviron continued in existence, its activities were sharply reduced, and scheduled flights were suspended by 1942.

Lydia was commandeered for military use as part of the Allied war effort and came under the control of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) between 1943 and 1944. During 1943 its four runways were extended to lengths ranging from 1,100-2,000 meters (3,600-6,560ft).

In 1944, as the German threat in the Middle East subsided, Aviron initiated service four times a week between Lydda and Haifa. The following year, at the end of World War II, Aviron looked forward to route expansion. However, all attempts at regular international passenger service were stifled by the negative attitude of the British Mandate government. Aviron therefore was limited to operating some charter flights. Its ‘fleet’ included a Dragon Rapide, two RWD 13s and an RWD 15, plus a handful of assorted even smaller aircraft. Most flights were within Palestine, but a few using the Rapide ventured to Nicosia, and even to some European capitals, including London.

Aviron’s postwar activity, however, was short-lived, as it was soon engulfed by the impending battle over the future of the Holy Land.

End of the British Mandate

With World War II over, the British announced their intent to end the mandate and pull out of Palestine as soon as practicable. The Jewish population, witnessing a continuing rise of Arab violence, desperately sought the means to defend themselves. Secretly, and against seemingly impossible odds, attempts were made to circumvent the British prohibition against Jews immigrating to Palestine or holding arms. On 29 November 1947 the United Nations General Assembly voted to partition Palestine into two separate countries. One would be a new Arab state. The other, only one-eighth the size of the homeland originally envisioned in Britain’s Balfour Declaration, would be the first Jewish state to exist in 2,000 years. Official Jewish institutions in Palestine reluctantly accepted the UN decision, but it was immediately denounced by Arab leaders. Soon the Arabs, determined to wipe out the Jewish state before it was born, streamed infiltrators across the borders and began to attack Jewish settlements. The British did little to prevent these assaults, jeopardizing the already precarious position of the Jews.

From the aviation standpoint, the Jews had only a ragtag collection of a few antiquated aircraft. Moreover, their use for defense or military purposes was prohibited by the British. Nevertheless, a secret Jewish air arm called Sherut Ha’avir (‘Air Service’) was formed in November 1947 to airlift supplies to the beleaguered settlements until the British withdrawal in May 1948, and to help defend the new State of Israel immediately thereafter. Aviron, the only commercial air service in Palestine, collaborated with the Sherut Ha’avir, providing aircraft for specific missions against Arab infiltrators and even procuring additional small types that could later be used, if necessary, for military purposes.

Although the Arabs living alongside the Jews in Palestine had no air force capability of their own, the surrounding Arab states—Egypt, Transjordan and Syria—as well as nearby hostile Iraq, amassed numerous fighter and bomber aircraft and threatened to attack the Jewish settlement immediately upon withdrawal of the British.

The Mahal

By late 1947 the Haganah Jewish defense force possessed fairly capable ground personnel, but a trained Israeli air force was nonexistent. Faced with a woeful and dangerous mismatch in the air defense effort against neighboring hostile Arab states, the Jewish population in Palestine was supported by pilots, supplies, and aircraft from other countries. These volunteers, from the United States, Canada, England, South Africa, Sweden, Holland, and elsewhere, became known as Mahal, the Hebrew acronym for Mitnaddevei Hutz la-Aretz (‘Foreign Volunteers’).

One of the principal allies for the Jewish cause was Al Schwimmer, in the USA. In 1947, with the backing of the Haganah, he formed Schwimmer Aviation in Burbank, California, to purchase and recondition war-surplus transport aircraft. The acquisitions included three Lockheed C-69 Constellations (the original military version of the civilian Model 49) and ten Curtiss C-46 Commandos. Eventually, the C-69s became EL AL’s first Constellations, and many of the C-46s also formed part of EL AL’s early fleet. In fact, Schwimmer’s original goal was to use these aircraft to help establish Israel’s first airline. However, when the Arabs rejected a partition of British mandate Palestine and threatened widespread armed hostilities, the goal soon shifted to fly these aircraft to Israel to help during Israel’s war of independence. Schwimmer’s group also recruited experienced aircrews and conducted pilot retraining. He was assisted by two other Americans from Boyle Heights in East Los Angeles who served with Schwimmer in the USAAF during World War II, Sam Lewis and Leo Gardner, both of whom were to later become captains for EL AL.

A tremendous obstacle soon confronted Schwimmer. The United States and nearly all other nations imposed an embargo against shipments of arms (including large transport aircraft) to Palestine—even though this action assisted the Arabs because they already had substantial supplies. To circumvent the restriction, Jewish interests formulated a clandestine scheme worthy of a spy thriller. They called it yekoom purkan (may salvation arise from heaven), a phrase of Jewish prayer. Among the participants were Schwimmer, Teddy Kollek (later to become mayor of Jerusalem), and Yehuda Arazi of the Haganah, one of the master spies of all time. The secret connection became Panamá. Tocumen Airport in Panama City had recently been built and was underused, a veritable white elephant. The Panamanian government, eager to develop the new airport, warmly accepted a proposal by the Jews to set up a privately owned airline, called Líneas Aéreas de Panamá SA (LAPSA). Schwimmer’s fleet would be registered to LAPSA and flown to Tocumen, ostensibly for commercial service. In reality, LAPSA would serve as a cover to spirit the aircraft out of the US and onward to Israel.

Schwimmer Aviation started overhaul work on the aircraft at Burbank during winter 1947-48. On 13 March 1948, the first of the Constellations, in LAPSA colors and with a Panamanian registration, was flown by Capt. Sam Lewis to Tocumen from Millville, New Jersey, via Kingston, Jamaica. The C-46s followed a few weeks later, although one was lost in a crash on takeoff from Mexico City. Each had been heavily overloaded with electronic equipment urgently needed for the anticipated war. Meanwhile, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation, having received information that the aircraft were ultimately destined for Israel, set off in hot pursuit of the two remaining Constellations and, at the last minute, seized them before they could leave the US.

Civil strife between Jews and Arabs in Palestine escalated sharply in January 1948, and the violence intensified with each succeeding month. The only country willing to sell arms to the Jews was, astonishingly, Czechoslovakia. Ironically, the Soviet Union, motivated by anti-British policy, supported the birth of the State of Israel. While the Soviets would not sell arms to Jewish interests directly, it allowed its satellite to do so.

The Jewish interests in Palestine, however, lacked any means of transporting the Czech arms in quantity. Moreover, Arab belligerency forced them to evacuate Lydda Airport and, when BOAC suspended service from London two days later, on 28 April, the Arabs were left in sole possession. Jewish air communications were then shifted north to Haifa and Ein Shamer. Other international air carriers fled to Cairo, leaving the Jewish community in Palestine isolated.

Meanwhile, as the fateful day of British withdrawal from Palestine approached, the Jewish volunteer pilots and technicians in Panamá hastened to prepare their aircraft for the trans-Atlantic flight to Africa and then to the anticipated new State of Israel, but time was running out. On 8 May, with preparations and crew training only partially complete, the first five C-46s took off for Israel via Paramaribo, Dutch Guiana (now Surinam); Natal, Brazil; Dakar, French West Africa (now Sénégal); Casablanca, Morocco; and Catania, Sicily.

As planned, on 14 May 1948 the British withdrew their remaining troops from Palestine. Immediately, David Ben-Gurion and other Jewish leaders proclaimed the independence of the State of Israel. The very next day the newborn state was attacked. Without warning, but not unexpectedly, Egyptian Douglas C-47 Dakotas (military DC-3s) bombed Tel Aviv and Supermarine Spitfire fighters attacked airfields. With Israel blockaded on all sides, its very existence depended on sea and air communications with a few friendly, but distant, countries. Fortunately the LAPSA aircraft began to arrive. Two C-46s landed at Ekron Air Base, south of Rehovot, on the night of 18 May. After disgorging their loads of precious equipment, they lifted off the next morning for Žatec, Czechoslovakia, to help in the arms airlift. The other C-46s proceeded directly to Czechoslovakia.

LAPSA’s lone Constellation slipped away from Tocumen on 19 May, under the command of Sam Lewis, with Maurice Kouffman as co-pilot, destined for Žatec. The new Israeli government then forged the Constellation and the C-46s into a somewhat autonomous group called LATA (Lahak Tovala Avirit, or ‘Air Transport Command’), under the direction of Munya Mardor, a Haganah arms-acquisition specialist who had been based in Europe. Lewis was appointed the chief pilot in charge of operations at Žatec.

LATA proved invaluable to the airlift. Arms included disassembled and crated Czech-built Avia C.210 (Messerschmitt Bf 109G) fighters, which on arrival in Israel were hurriedly assembled for immediate action. By 29 May the first four fighters were launched over Israeli skies, ending the dominance of the Egyptian Air Force during the first two weeks of the War of Independence. Israeli pilots shot down some Egyptian aircraft, and the Arabs unexpectedly abandoned their air offensive shortly thereafter. The arms airlift continued until shut down by the Czechs in August 1948. Ninety-five precious trips were flown, carrying 25 Avia fighters, spare parts, flying personnel, and 350 tons of munitions to Israel.

Early in July 1948 the Israel Defense Forces managed to recapture Lydda Airport (renamed Lod upon Israel’s independence). However, the airport had been extensively damaged by the Arabs and required much reconstruction. Not until 24 November 1948 was Israel able to announce that Lod Airport was ready anew for regular civilian air traffic, which began on 1 December.

Meanwhile, two war-surplus Douglas C-54s Skymasters (DC-4s) had been acquired in May in Europe and used as arms transports, bombers, and as the lead aircraft for flights of Spitfires (also acquired in Europe) from Czechoslovakia to Israel. Also that month, four C-47s were flown from South Africa and used for transport and bombing operations.

On 22 August 1948 Israel launched the appropriately named Operation Dust to save Jewish settlements in the south (the Negev) cut off from the main part of Israel by Egyptian troops and accessible only by air. A 1,230-meter (4,030ft)-long dirt runway was built near the desert settlement of Ruhama, about 40 kilometers (25 miles) south of Ekron. Because of the danger of Egyptian attack, flights to the airstrip had to be made at night, and there were no radio beacons or other navigational aids. As each airplane approached in the dark it would flash signals. Kerosene-filled smudge pots lining the runway would be lit, and the aircraft would land in a cloud of dust. This operation lasted two months and totaled 417 flights, mainly between Ekron and Ruhama, moving 2,200 tons of supplies and 1,900 personnel into the Negev, and returning many wounded and exhausted men to central Israel. Operation Dust helped saved the Negev during the War of Independence.

The heavy transports were piloted almost exclusively by Mahal volunteers, because few Israelis had the necessary experience and those who might have been qualified were assigned to other pressing tasks.

By late summer 1948 the Israelis had at last secured the upper hand in the conflict. Although the signing of an armistice was still several months away, the nation could at least see the way clear to the start of normalcy, including the resumption of civil aviation. The stage was set for the founding of Israel’s national airline: EL AL.

Last updated 9 March 2021

Copyright 2021, Marvin G. Goldman