Bring back my sons from afar and my daughters from the ends of the earth (Isaiah 43:6)

In EL AL’s history, the years 1951 to 1957 are known as the ‘lean years’. The drama, euphoria and harried improvisation of the first 24 months of operation had subsided. Now the airline was trying to settle into a normal commercial operation—and times were hard on Israel and on EL AL.

The young country faced the huge task of providing food, lodging, work, education, and medical care for hundreds of thousands of penniless new immigrants from all parts of the world. Israel’s economy was in shambles, and travel and trade faced austerity and severe limitations. Serious doubts persisted as to whether such a small state would be able to maintain an airline that could successfully compete in the international arena and not be a drain on the nation’s resources.

Meanwhile, EL AL was barely managing with its small fleet of unpressurized Douglas DC-4 and Curtiss C-46 aircraft. Its direct competitors from Europe and the United States were already using larger and pressurized aircraft, such as Lockheed Constellations and Douglas DC-6s.

With constraints on equipment and finance, EL AL struggled to survive. Every facet of the company needed improvement, from organization and management policies to technical, operational, and customer service standards. Added to this was the desire to integrate Israeli personnel, particularly into the higher ranks of captains.

Schwimmer’s Constellations

As for aircraft, EL AL turned to Al Schwimmer for assistance. Schwimmer had been instrumental in acquiring the C-46s spirited out of the US to Israel via Panamá for use in the War of Independence, several of which eventually joined EL AL’s early fleet (see Chapter 1). He had also purchased three surplus Lockheed C-69 Constellations from the US War Assets Administration which received some basic rehabilitation by his company with a view towards service as civilian or military transports in aid of Israel. Only one found its way to Israel; the other two were impounded by the FBI. With Israel’s War of Independence over, Schwimmer regained ownership of all three aircraft and refurbished them for commercial use at Burbank, California.

Schwimmer’s Constellations were all of the earliest type, but they were just what EL AL needed. Now for the first time EL AL would have pressurized aircraft, capable of flying higher than the DC-4s and C-46s and avoiding bad weather more frequently. The Model 49 Constellation (as the civilian equivalent of the military C-69 was designated) had a service ceiling of 7,700 meters (25,000ft), with a typical cruising speed of 440km/h (275mph) and an average range of 3,900km (2,400mi).

In October 1950 EL AL purchased the first two of these ‘Connies’, as the type was affectionately called, registered as 4X-AKA and 4X-AKB. The third Connie (4X-AKC), bought in April 1951, was the same one that had served in the Czech arms airlift of the Israeli War of Independence, while under Panamanian registration.

Schwimmer had to convert the interiors from their bare military layout, improve cabin heating, ventilation and insulation, and install extra windows; engines were also upgraded, allowing increases in maximum gross and landing weights. After painting into EL AL’s new royal blue and silver colors they were flight-tested by Lockheed.

The first ready for delivery was 4X-AKB, which arrived at Lod Airport on 22 December 1950 following a flight from New York under the command of Captain Sam Lewis with First Officer Leo Gardner. Dignitaries aboard included Al Schwimmer; Yehuda Arazi, the Israeli undercover agent who helped mastermind the acquisition of arms for the War of Independence; and Levi Eshkol, treasurer of the Jewish Agency and later prime minister of Israel. It was a momentous occasion to have those who contributed so much to the birth of the State of Israel now participate in a major step forward in the development of EL AL.

EL AL’s ‘new’ Constellation, initially named Mazal Tov (‘Good luck’), was placed into service on 28-29 December 1950 with a charter flight from Tel Aviv to New York, carrying members of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. At the end of January 1951 this aircraft entered scheduled service to Paris and London.

![EL AL's first baggage label featuring Constellation aircraft, 1950-52 [Marvin G. Goldman collection ('MG')]](http://www.israelairlinemuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/1952-ca.-EL-AL-Red-and-Blue-Constellation-Label-MGGoldman-Colln.jpg)

On 25 March 1951 the second Connie (4X-AKA) arrived in Israel. This had been converted to a Model 149 with increased fuel capacity, resulting in an additional 900km (550mi) of range. EL AL’s Connies generally operated in an all-tourist layout of about 63 seats. This was unusual, because most scheduled airlines offered all first class seating until economy class was introduced in 1952.

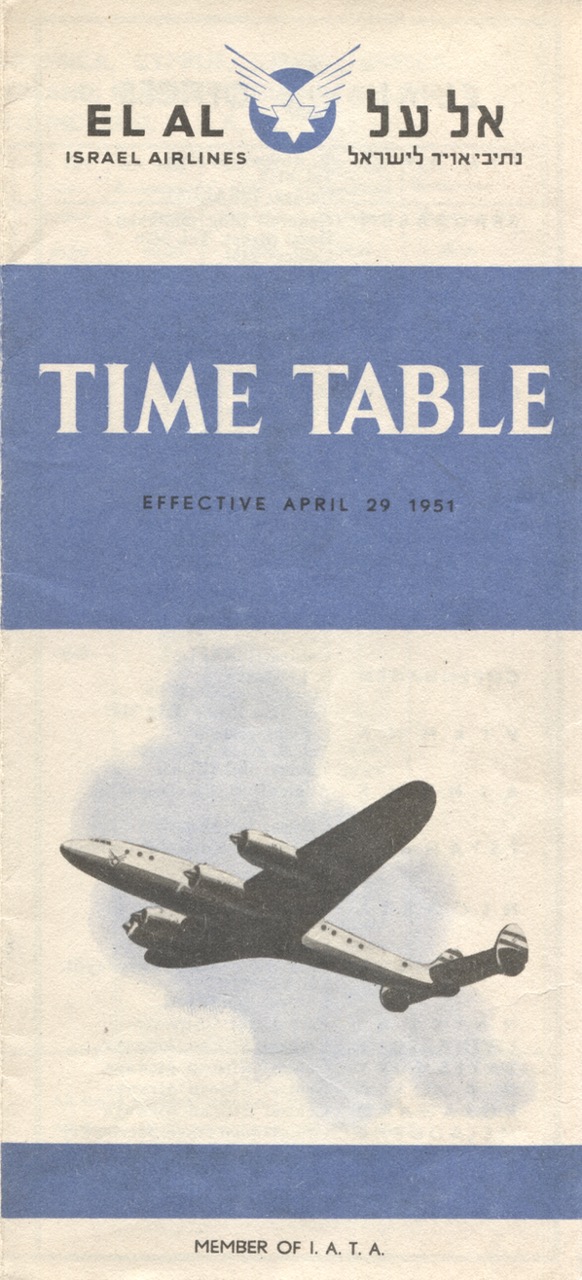

Scheduled Service to New York

Although EL AL had been flying to the United States since June 1950, these flights had been charters. With the arrival of a second Constellation, scheduled service to New York began on 29 April 1951. EL AL thus became the 11th airline offering scheduled service over the North Atlantic route—and the first based outside North America and Europe.

Connie Routes

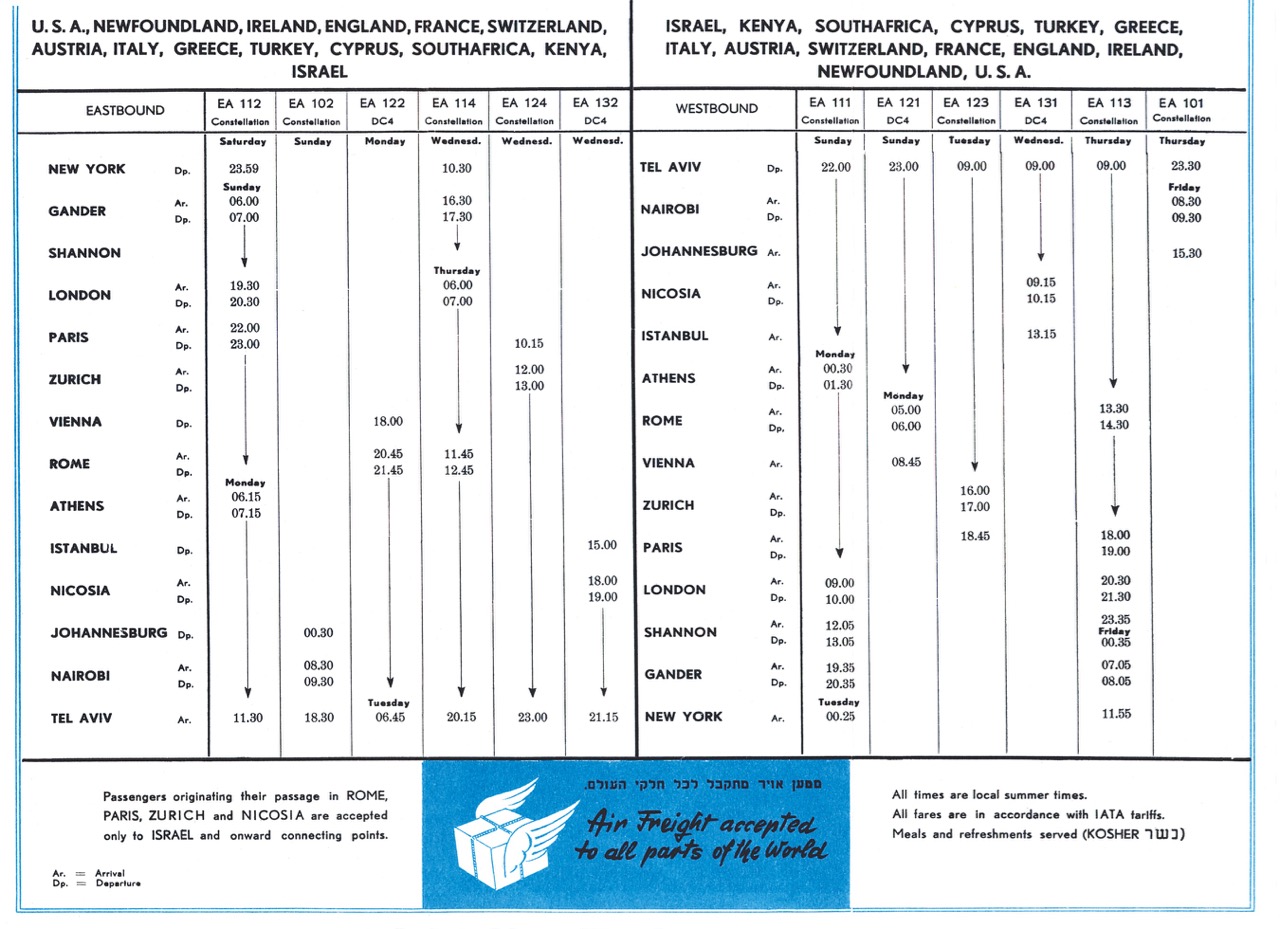

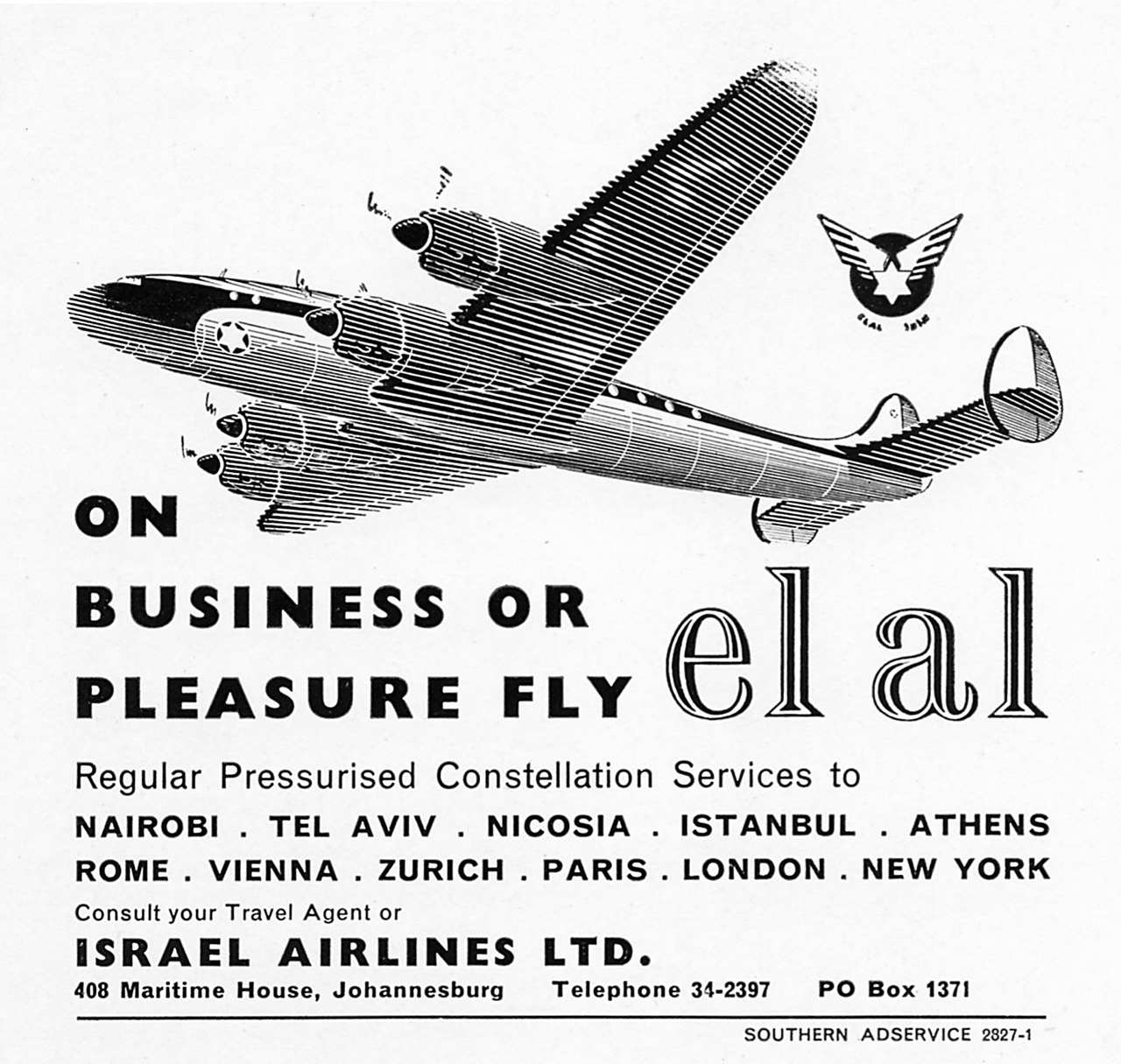

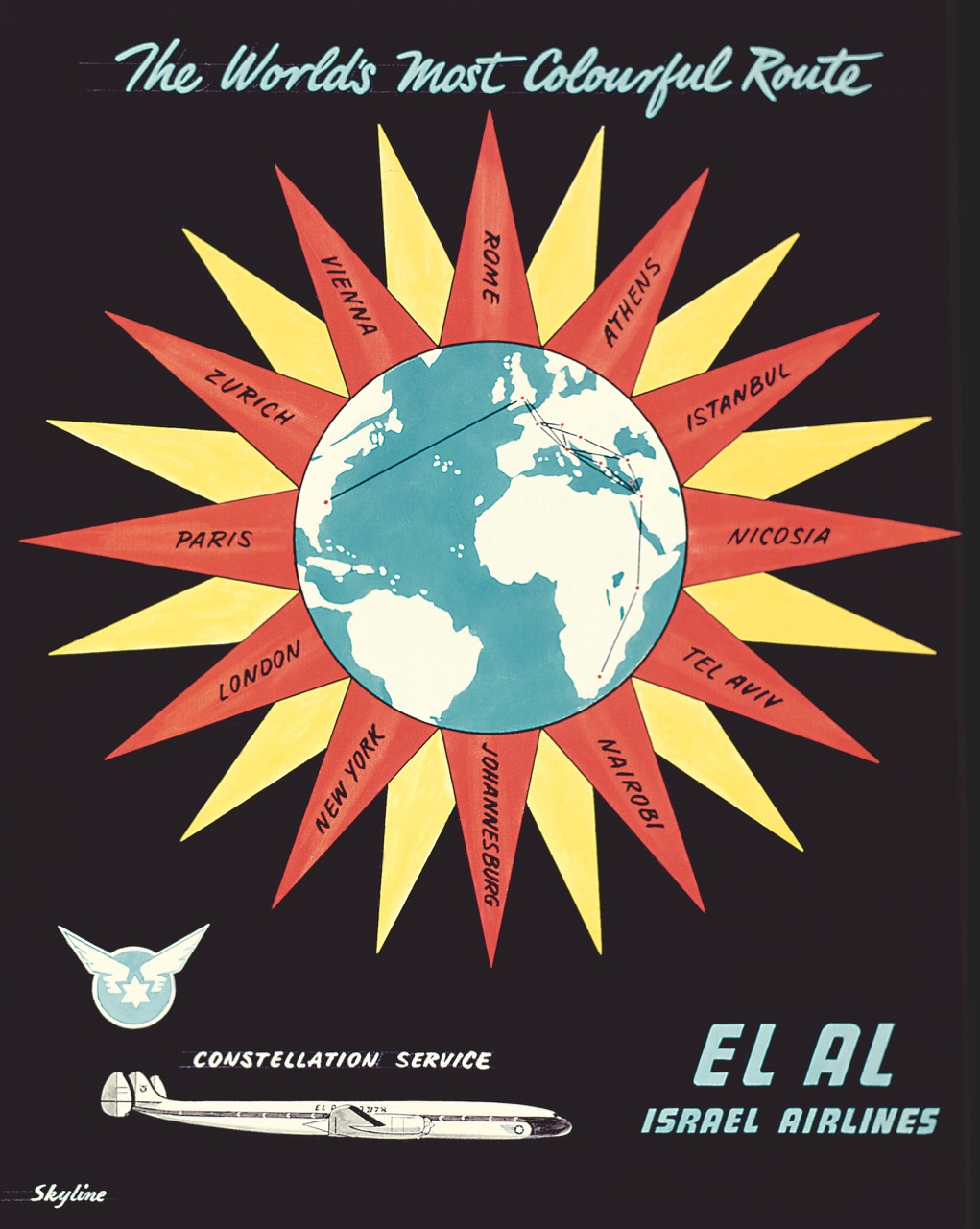

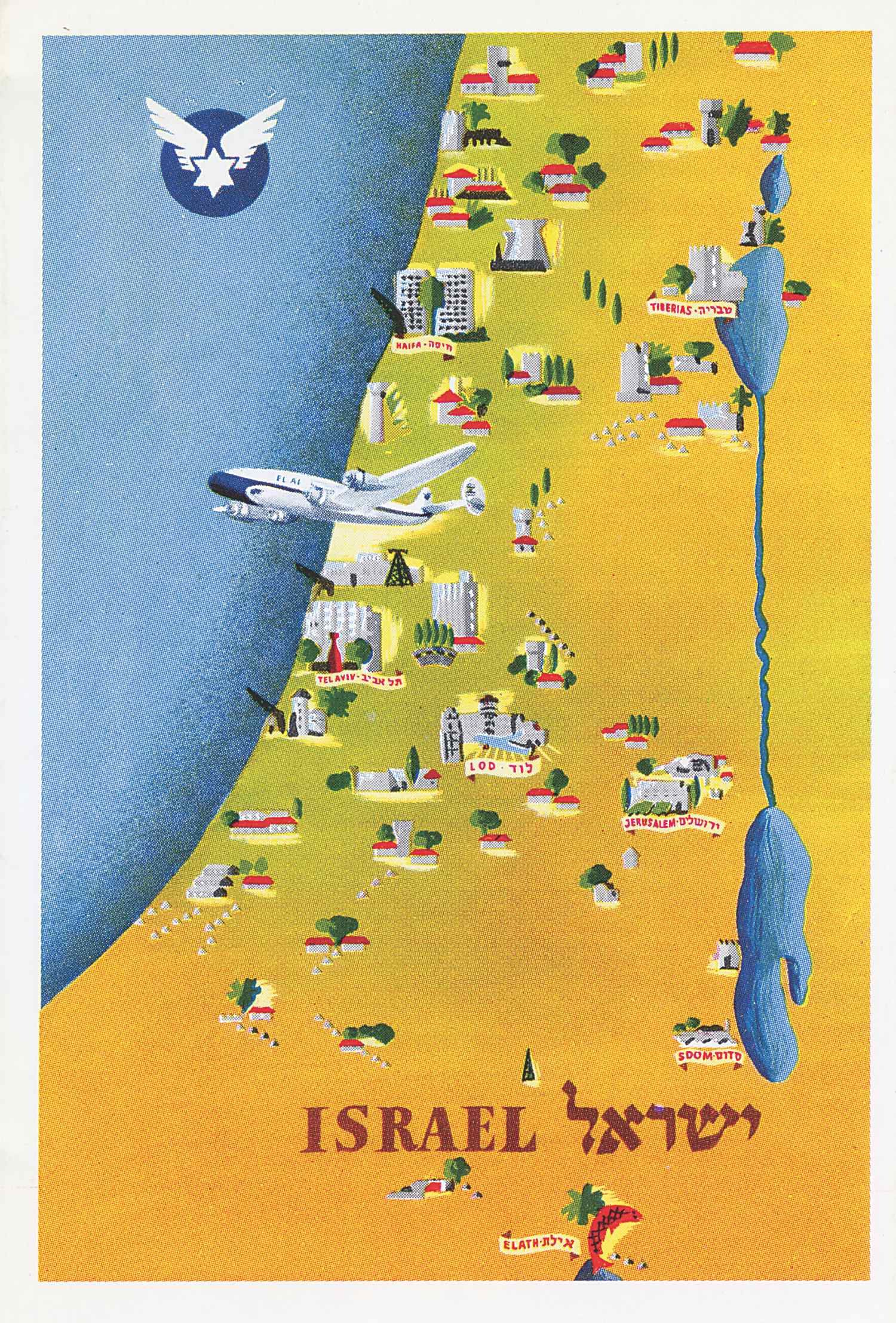

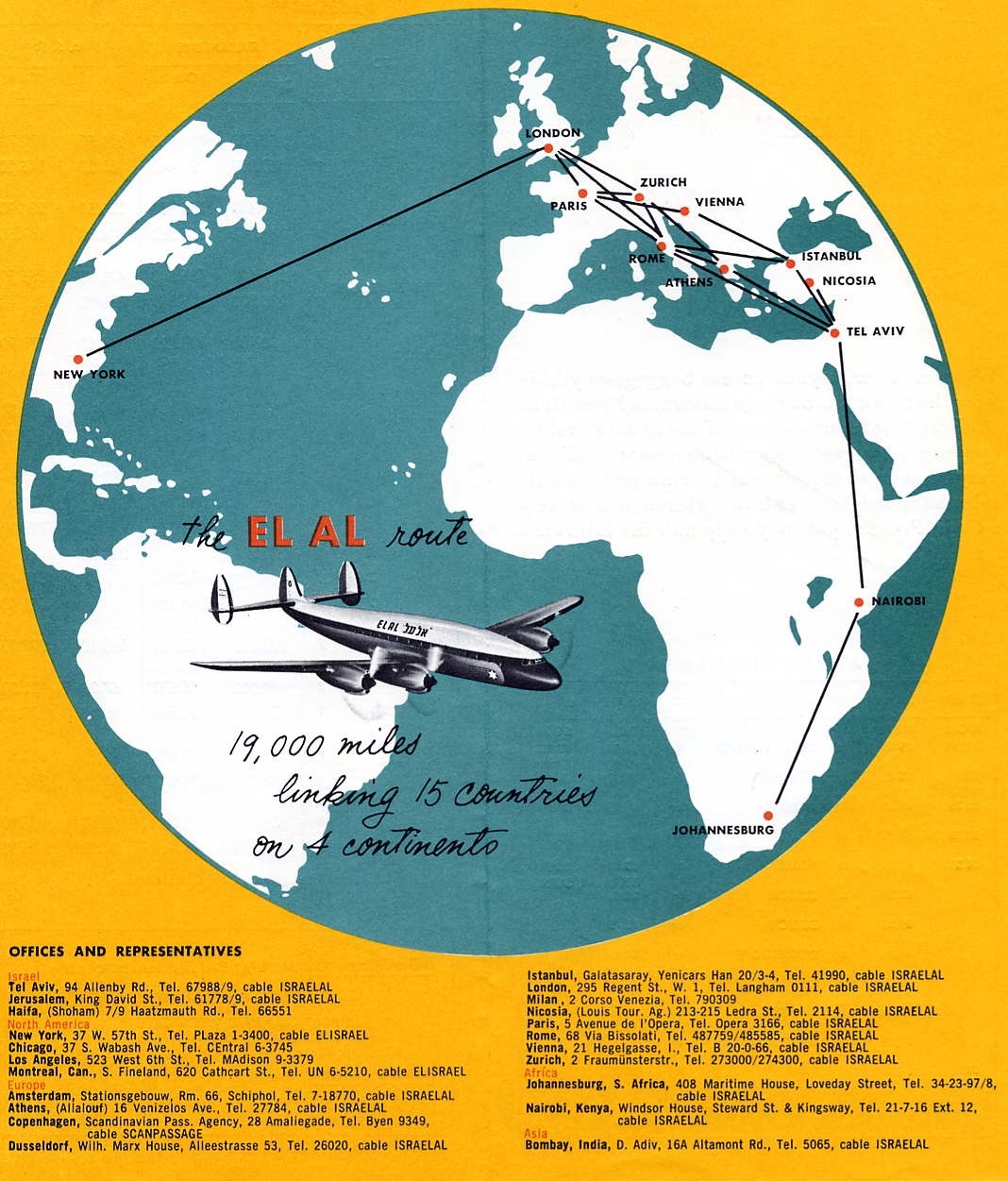

The Constellations plied the same routes that had been pioneered by EL AL’s DC-4s. EL AL served 12 cities: the home base of Tel Aviv (Lod Airport); London, Paris, Zürich, Rome, Athens, Vienna, Nicosia and Istanbul in Europe; Nairobi and Johannesburg in Africa; and New York. The usual refueling stops on the trans-Atlantic route were at Gander, Newfoundland, and Shannon, Ireland.

A typical weekly flight schedule included two Constellation services to New York (with three to five stops, always including London); one Constellation roundtrip to Paris via Zürich; one Constellation rotation to Johannesburg via Nairobi; one DC-4 trip to Vienna via Rome; and one DC-4 service to Istanbul via Nicosia. A flight between Tel Aviv and New York—if all went well—took between 28 and 33 hours, depending on direction and winds.

On 8 August 1951 the third Constellation (4X-AKC, another Model 149) arrived at Lod Airport. This addition, combined with substitution of C-46s for DC-4s on the shorter routes to Vienna and Istanbul, allowed the complete phaseout of the DC-4s by April 1952.

A fourth Connie (4X-AKD) was acquired from the US, allowing an increase in trans-Atlantic service by July 1954 to thrice-weekly. Route expansion occurred in March 1956 when EL AL added the first new scheduled destinations in five years: Amsterdam and Brussels.

By summer 1957 EL AL was operating an all-Constellation passenger service, except that Douglas DC-6Bs were chartered from UAT (Union Aéromaritime de Transport) for the weekly roundtrip to Johannesburg (and later from SABENA of Belgium, as well as Super Constellations or DC-7Cs from KLM Royal Dutch Airlines).

Problems, Problems

The Connies were temperamental. Mechanical problems were frequent, and a general shortage of spare parts caused frequent delays and schedule disruptions. Often an aircraft would be grounded, perhaps in Iceland or Khartoum, waiting for a scarce replacement engine. One of the Connies was dubbed ‘The Turkish Bath’ as its air conditioning was ‘temporarily’ out of order most of its life with EL AL. The cabins were not that well insulated, and the high interior noise level from ‘pounding piston engines’ made the long flights seem even lengthier.

Published timetables only compounded the problems. They were usually issued late, with numerous errors, and schedule changes were frequent. More importantly, they called for the four Connies to be flown between two and four hours per day more than the average utilization of similar aircraft by other airlines. This over-ambitious plan could not be realized.

Public relations had a hard time. One of their biggest jobs was to convince customers that EL AL was a ‘real’ airline and not simply an immigrant carrier. (In the early years, most of the company’s revenue was derived from such activity.) Yet the frequent delays meant that EL AL still appealed mainly to air travelers sentimental about its ties to Israel. They joked that EL AL really was an acronym for ‘Every Landing Always Late’, and referred to the fleet as the ‘EL AL Cancellations’. Nevertheless, during this period EL AL maintained a flawless safety record, and its load factor was one of the highest of all trans-Atlantic airlines.

Another issue that rankled Israelis was the high number of foreign crew members. Pilots in the early years of EL AL could be divided into three distinct groups: foreigners (airmen recruited from Mahal and overseas air carriers, predominantly Anglo-Saxon in language and culture); semi-foreigners, former US and British military personnel, mostly Jewish, suspended between two worlds, Zion and the rest of the universe—from New York, Los Angeles and London—captivated by the new state yet uncommitted, and who because of language, interests and salaries tended to gravitate toward the foreign element; and native Israeli pilots, such as Oded Abarbanel, Uri Breier, Yitzhak Hennenson, Zvi Tohar and Shmuel Wedeles.

By 1954, however, the slow but steady shift to an Israeli crew emphasis had become decidedly noticeable. Many Israeli radio operators and some co-pilots and assistant flight engineers now served in EL AL. Zvi Tohar became the first Israeli to be licensed to command Constellations, in 1953. Only 50 foreign air crew remained by 1954, and some of them, such as Bill Katz from Florida, George (Gad) Katz from Rhodesia, and Danny Rosin from South Africa, became Israeli residents.

Maintenance

Originally, EL AL’s aircraft maintenance was mainly contracted out. For example, overhauls on the Constellations were initially performed by companies operating out of Idlewild Airport, New York. From the beginning, EL AL wanted to develop its own complete maintenance base at Lod Airport. Progress was slow, but with hard work local capabilities advanced. Early Israeli technicians, such as Dov Rafaelovitch and David Yacov, furnished the ambition and helped develop the skills that later transformed EL AL maintenance into a premier operation admired by the industry. By 1954 70% of all technical work was handled at Lod, and only 60 of the imported engineers remained.

Meanwhile, Al Schwimmer was also working to help make Israel self-sufficient in aircraft servicing. In October 1953, with input from his own maintenance company, Israel Aircraft Industries (IAI) was established at Lod Airport under the original name of Bedek–Government Aircraft Overhaul Depot (Bedek means ‘inspection and maintenance’). IAI’s mission was to act as an overhaul center primarily for the Israeli Air Force, with the servicing of airliners transiting Tel Aviv as a secondary function. Within three years IAI completed an impressive base at Lod, capable of doing complete engine repairs and 1,000-hour airframe checks. In March 1956 IAI’s success led to a proposal to transfer EL AL’s line and engine maintenance work to IAI. The airline’s mechanics vigorously resisted this move. A government investigating committee was convened and decided in favor of independent EL AL maintenance, a policy that has continued with beneficial results to this day.

The Search for New Aircraft

By 1953 EL AL realized that its early model Constellations were becoming obsolete. As in the DC-4 era, its competitors on the trans-Atlantic run were already flying more advanced types, with greater comfort, range and reliability.

Yet EL AL’s financial resources were extremely limited, and it could not afford better aircraft. At first, in July 1953, it considered a novel plan to upgrade its piston-engine C-46s with a small turbojet engine, developed by aeronautical engineer Dr. Erich Schatzki, that would be manufactured by Société Turboméca of France. They were to be mounted in pairs, like jet pods, allowing the capacious aircraft to carry an additional 4,500kg (10,000lb) of payload. This scheme was never implemented, and instead a fourth Constellation joined the fleet.

A year later EL AL considered buying some Model 1049E Super Constellations to replace the older 49s, but deferred a decision. Plans were also formulated for the possible sale of up to $3 million (equivalent to about $26 million today) of stock to the public; again, this did not go through.

The competitive disadvantage became even more acute by 1955. A proposal from The Flying Tiger Line, a US charter and cargo carrier, to furnish new Lockheed 1049G Super Constellations in exchange for 26% of EL AL’s shares of stock, and other proposals for acquiring later model used Constellations, were never accepted.

Meanwhile, Aryeh Pincus, EL AL’s president, preferred a bold leap forward. Britain’s Bristol Aeroplane Company had designed a new type: a four-engine turboprop with a passenger capacity nearly twice that of the Connie and a long-range capability and speed ideal for EL AL’s requirements. Called the Britannia, each airliner would cost four and a half times the cost of a used Connie, but it represented a technological revolution. Turbine power would offer a new dimension in smooth and quiet flight, with ample power to operate economically nonstop across the North Atlantic even against the prevailing winds.

After much persuasive work, Pincus convinced the government to select the Britannia, and a firm order for three Series 300s, with an option for a fourth, was signed on 22 June 1955. EL AL thereby became the first airline apart from Britain’s state-owned BOAC to order this ‘jet-prop’.

Tragedy Strikes

Just as EL AL was glowing over the signing of the Britannia order, it suffered a stunning loss. On 27 July 1955 its Constellation 4X-AKC lifted off from Vienna bound for Tel Aviv with 51 passengers. Looking after them was a crew of seven: Captain Stanley Hinks, First Officer Pinchas Ben-Porat, Flight Engineer Sydney Chalmers, Radio Operator Rafi Goldman, Stewards Albert Alkhadaff and Leon Tiser, and Stewardess Sara Acharkan. The date was the 9th of the month of Av in the Jewish calendar, a traditional day for mourning the greatest tragedies in Jewish history. The flight, regularly scheduled LY402, had originated in London the day before and also stopped at Paris. Its route from Vienna channeled the aircraft along a narrow air corridor over Yugoslavia near the Bulgarian border.

Flying at a height of 5,400m (17,700ft) in the early morning twilight, the Constellation was intercepted by Bulgarian MiG-15 jet fighters. They directed the airliner to lower its landing gear and proceed to a military air base west of Sofia. Complying, the airplane descended to an altitude of about 600m (2,000ft). Suddenly, without warning, the MiGs opened fire with machine guns and 20mm cannon and the Connie crashed in flames near the Greek border. There were no survivors.

The shooting down of the Constellation plunged EL AL into gloom. Flights were canceled pending a study of the tragedy and a reassessment of the company’s future. Skeptics intensified their criticism of the airline as an unnecessary luxury. The Britannia decision was still under fire. Strong vocal opposition existed to the losses accruing from the trans-Atlantic routes. To reach profitability, the load factor (that is, the number of passenger seats occupied as a percentage of those available) would have had to rise to an impossible 102%. Suggestions arose that EL AL confine itself to ‘essential’ flights and regular service to Europe. It seemed that EL AL had reached the nadir of its fortunes.

Management, however, was convinced that the only way out was development, not retrenchment. They believed that no country, and particularly not Israel, could afford the luxury of depending entirely on foreign carriers to keep the lines of exterior communications open. They also believed in the ultimate economic viability of Israeli airline operations. Flights were resumed, and another Constellation (4X-AKE) was acquired in October 1955 as an interim measure to replace the destroyed aircraft.

The Sinai War

The despair and doubts about EL AL changed dramatically with the outbreak of the Sinai War on 29 October 1956. For over a year preceding the conflict, Israel confronted fierce attacks along its eastern border with Jordan, while the Gaza Strip at its southwest had been turned into an Egyptian-supported fedayeen guerrilla base. Meanwhile, directly south at Eilat and the Red Sea, Israel’s communications by sea and air were under siege. Egypt proclaimed a blockade of Israeli shipping through the Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba, pointing its guns overlooking the Straits of Tiran (a narrow lane connecting the Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba) that Israeli shipping would have to navigate to keep Eilat and the southern Negev alive. Egypt also closed the airspace over the Straits of Tiran on 3 September 1955, thereby forcing EL AL to abandon its direct route from Tel Aviv over the Gulf of Aqaba, Straits of Tiran and Red Sea down to Nairobi (Kenya) and Johannesburg (South Africa). Instead EL AL had to cope by chartering aircraft of foreign airlines to fly to Johannesburg via a circuitous route through North and West Africa, starting in early 1956.

On 26 July 1956 Egypt’s President Nasser acted further by illegally nationalizing the Suez Canal. Three months later, In coordination with the British and French who were anxious to protect their own interests in the Suez Canal, Israel invaded the Sinai Peninsula in an effort to keep its Red Sea transportation lanes open.

All foreign airlines immediately stopped flying to Israel. The country was surrounded by unfriendly states to the north, east and south. As in the War of Independence, Israel’s only swift line of communication to its nearest friends and allies was by air over the Mediterranean Sea.

EL AL was the only airline that flew passengers in and out of Israel during the campaign, a difficult task as many pilots were called to active duty by the Israeli Air Force. Other crews were requisitioned to fly EL AL aircraft that transported ammunition and supplies from Paris to Israel. Under international pressure, Israel and its allies ultimately withdrew from the Sinai. Israel did regain access by sea to its Eilat port. However, Israel and EL AL were still denied the right to operate flights over the same waterways, and did not regain that right until the conclusion of the Six-Day War in 1967.

Public doubts about EL AL ended with the Sinai War. The Israeli government understood anew that in times of war, when all other airlines suspend flights to Israel, only EL AL can be counted on to continue operations. Pride replaced criticism in the public’s mind. There were no more calls to trim routes. Now the government committed to building EL AL into a major international airline by firmly supporting the airline’s decision to buy the Britannia.

A New Era, and New Leadership

The Sinai Campaign also signaled the beginning of a new era. Sweeping managerial and organizational changes were about to transform EL AL, as the debt-ridden airline moved swiftly from piston- to turbine-engine aircraft, from adolescence to maturity, from losses to profitability, and from an immigrant carrier to a significant international competitor.

The government decided that the airline needed a new leader who would reduce the losses and respond more quickly to technological innovation. It chose Efraim Ben-Arzi. Pincus left to become top man of the Jewish Agency.

Born in Poland, Ben-Arzi was an engineering graduate of Grenoble University in France and ended World War II with the highest rank obtained by a Palestinian Jew serving in the British Army—Lieutenant Colonel. Later he rose to the position of major general in the Israeli Defense Forces and head of logistics and supply. A strong and controversial leader, attracting both admirers and critics, he learned the airline business quickly and made highly beneficial key decisions.

Ben-Arzi worked for more efficient use of manpower and equipment and emphatically endorsed the decision to purchase the Britannia. His main policies and views are as strikingly modern today as they were half a century ago: that the small size of the host country does not limit the traffic potential of its national carrier; high equipment utilization is a must—it reduces unit costs; and the successful airline must emphasize manpower skills and the best exchange of information. While recognizing that the usefulness of an airplane is not always related to its age, Ben-Arzi nevertheless maintained that fashion and ‘having the latest’ are very important factors, and to compete one must advertise. Publicizing new equipment will draw the public away from the older airplanes.

With these policies in place, and the Britannia order firmly on the books, EL AL was poised for one of its boldest steps forward.

Last updated 1 August 2023.

Copyright 2020-2023, Marvin G. Goldman