Behold, He who keeps Israel neither slumbers nor sleeps (Psalms, 121:4)

Even while EL AL’s turboprop Britannia aircraft were achieving unparalleled success and the airline was still trying to swallow its then-enormous investment, management realized they could not relax. They had to prepare for the swiftly approaching age of pure jet aircraft.

The world’s first pure jet airliner, the British de Havilland Comet, had entered service in 1952, but had suffered a sharp setback from crashes caused by catastrophic structural failure. By 1955 work was underway on a much improved Comet 4. Boeing responded by investing heavily in developing its first pure jet passenger aircraft, the Boeing 707. Meanwhile, Convair and Douglas decided to go forward with competitive designs that became the Convair 880/990 and Douglas DC-8 respectively. Boeing made faster progress than anticipated, and by October 1958 Boeing 707s were in service with Pan American, earning the acclaim of airlines and passengers alike.

Boeing, Convair and Douglas all competed to sell EL AL their respective new jet offerings. EL AL assigned a team, including Col. Shlomo Lahat, its new Vice President under President Efraim Ben-Arzi, and Benjamin Davidai, then the number two head of Maintenance and later Senior Vice President-Operations of EL AL, to evaluate the benefits and possible drawbacks of each type. Davidai, who was particularly sensitive to the technical capabilities and economics of the various aircraft types, strongly recommended that the best choice for EL AL would be Boeing’s 707. As a result, only a few months after the first Britannia entered service, EL AL began negotiations for the purchase of new four-engine pure jet 707s being developed by Boeing in Seattle, Washington. Moreover, Davidai urged EL AL to select Rolls-Royce Conway ‘bypass’ engines for its first 707s. The Rolls-Royce engines provided more thrust and used less fuel than, the early Pratt & Whitney engine models that most airlines had been selecting for their 707s, and were ideal for EL AL’s transatlantic service .

As a result, EL AL ordered three Boeing 707 Intercontinental models powered by the new Rolls-Royce engines. Designated as the ‘707-420’ model, it could fly nearly 50% faster than the Britannia, with a maximum cruising speed of 965km/hr (600mph). Also, the 707-420 had a range with typical payload of up to 9,260km (5,754mi), and a maximum payload of 28,850kg (57,000lb). This acquisition entailed a new level of expenditure for EL AL, but fortunately it had developed a good credit standing with Chase Manhattan Bank since the Constellation days, and it obtained a loan for 80% of the cost of the 707s.

The 707s required longer and stronger runways for takeoffs and landings than those commonly existing at the world’s commercial airports. To accommodate the 707s, Lod Airport extended its main runway in November 1960 to 2,658m (8,720ft).

EL AL’s First 707s in Operation

EL AL originally planned to introduce the 707 in summer 1961. However, competition from other airlines already flying turbojets did not allow the luxury of waiting, and EL AL was forced to advance its plans. Weekly Tel Aviv–New York service began on 8 January 1961, with a 707 leased from Varig of Brazil; from 19 February 1961, frequency increased to twice-weekly.

On 7 May 1961 EL AL took delivery of its first owned 707 (registered 4X-ATA) in a ceremony at Boeing Field, complete with blessing by rabbis and 250 attendees. Captains Sam Feldman and Zvi Tohar commanded the delivery flight to Israel.

EL AL set three world records with 707 4X-ATA on 15 June 1961, during the return portion of its maiden passenger service—from New York to Tel Aviv: (1) the fastest flight from New York to Tel Aviv, 9hr 33min; (2) the first nonstop service between New York and Tel Aviv; and (3) the world’s longest nonstop scheduled commercial flight (9,270km/5,760mi). Piloted by Captains Tom Jones and Danny Rosin, the aircraft carried 97 passengers at a cruising altitude of 12,500m (41,000ft).

On 10 June the second 707 (4X-ATB) was delivered. During the 1961 summer season, six roundtrip Tel Aviv–New York services were operated a week with the two 707s, plus two roundtrips with Britannias. All flights called at either London or Paris, except for a weekly nonstop from New York to Tel Aviv with a scheduled flying time of 9hr 55min. A Tel Aviv to New York nonstop was considered, which would have had to confront unfavorable westerly winds; however, this was rejected because even under optimum conditions only about 30-40 passengers could have been carried, a financially marginal operation at best.

Initially, the 707s carried only a limited payload—up to 115 passengers and no freight, but it was soon discovered that most restrictions could be relaxed. The passenger limit was raised to 158 (except for 120 on the New York to Tel Aviv nonstop), although still without any cargo being carried.

The 707 proved to be a great success, and the increased frequency of service was complemented by trans-Atlantic load factors exceeding 60% on a year-round average—a figure at or near the top of all airline performance at the time. Israel was no longer so ‘far away’ to passengers from the US. The 30-hour flights on vibrating and noisy Constellations were now only distant memories. In 1961 EL AL’s share of total air passengers arriving in Israel rose to an estimated 55-60%. In all, EL AL carried 171,068 passengers during its fiscal year ended 31 March 1962, nearly 50% greater than the previous year.

On 15 October, following the 1961 peak season, the last two Constellations were retired from European schedules, marking the end of the piston-engine era for EL AL.

EL AL’s ‘Bar Mitzvah’ Year

On 15 February 1962 EL AL took delivery of its third 707-420 (4X-ATC). For that year’s summer schedule EL AL offered a new high of nine roundtrips per week to New York. One included a nonstop New York–Tel Aviv return; the other flights were routed through European cities, including London, Paris, Amsterdam, Rome and Athens. On 11 June service was inaugurated to Frankfurt, Germany, with two roundtrips per week from Tel Aviv. The operation of all three 707s provided an exciting atmosphere for 1962—celebrated as EL AL’s 13th or ‘bar mitzvah’ year. EL AL carried its one-millionth passenger that year, and held many special celebrations. The airline had come a long way since its first improvised flights on converted aircraft borrowed from the Israeli military air transport command.

EL AL’s Answer to the Arab Boycott

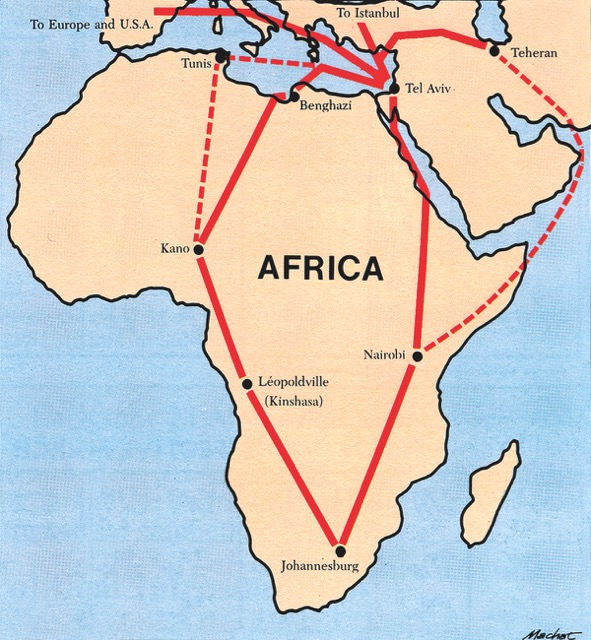

In March and April 1962 EL AL accepted delivery of two Boeing 720B medium-range jets. This acquisition directly related to the Arab boycott. From late 1955, in order to reach Johannesburg, South Africa, without flying over or too close to Arab-controlled airspace, EL AL had to charter piston-engine aircraft from other airlines that took a circuitous route via North and West Africa. The 720Bs had the necessary performance to allow EL AL to resume flying to South Africa with its own aircraft—via an exaggerated route stopping at Teheran, Iran—and they were chosen for that reason. With powerful Pratt & Whitney engines and an improved wing over that of the 707, the 720B could take off from ‘hot and high’ Teheran with sufficient fuel and payload for the desired flights.

As soon as possible, on 14 June 1962, the 720Bs took over service from Tel Aviv east to Teheran, then flew southwest across the Persian Gulf to Nairobi and then south to Johannesburg, adding 3,860km (2,400mi) to the trip to Johannesburg. A direct route south via the narrow Gulf of Eilat, over the Tiran Straits and Red Sea and then to South Africa was not feasible because of Egyptian hostility. This 16-hour endurance test was one of the world’s most circuitous air routes, with some 25 heading changes to prevent overflying hostile areas. Radio aids were sparse. High elevation and temperatures, plus a heavy fuel uplift, limited aircraft performance and thus the payload. Double crews had to staff the aircraft. To achieve the break-even point, the route had to show an 85% load factor.

Starting with the 1962 summer schedule, the 720B also replaced the Britannia on the Tel Aviv to Europe routes. This move secured a large slice of the international travel market, and the percentage of non-Jewish passengers edged closer to 40%. EL AL gained acceptance not just as an ethnic and immigrant carrier, but also as a successful and established international mover of passengers and cargo.

In 1965, to increase efficiency and performance of its 720Bs, EL AL replaced the original JT3D-1 turbofans with more powerful JT3D-3Bs. This also enabled standardization with two Pratt & Whitney-powered 707-320B aircraft, ordered for delivery staring in late 1965.

With a fleet of five new Boeings and a pair of Britannias, EL AL settled in for expected steady growth during the mid- and late-1960s. Not all went as planned, however, and before the decade drew to a close, EL AL had to survive many trials, including labor unrest, battles with charter flights, management changes, attempts at government political intrusion and—most serious of all—a war for the very survival of Israel.

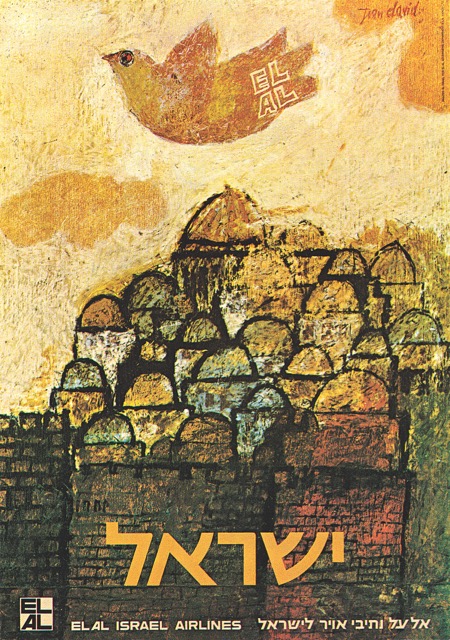

Basic Policies: EL AL’s Relationship to Israel

EL AL’s two main policies in the 1960s followed those established upon its founding. First, it should be operated as a profitable business, as independent as possible from state interference. The expected financial strength from this policy would help EL AL fulfill its second basic tenet, the standby one of serving as a lifeline to the world for the State of Israel in the event of war or other emergency.

On the other hand, with the maturing of EL AL and modernization of its fleet, other policies became prominent. Long-range planning objectives, more sophisticated budgets and financial safeguards, as well as uniform work procedures, were developed and constantly reviewed. EL AL also had to deal with its new crucial role in Israel’s economy. Profits, as well as tourism to Israel promoted by EL AL, represented valuable foreign exchange to the young state. With its world-wide network of offices and advertising activities, EL AL became the leading promoter of tourism to Israel—to the point in the 1960s where it spent over twice the amount of the combined budgets of all the relevant tourist institutions in Israel to attract visitors. With a policy of promoting Israel first, and itself second, EL AL regularly brought travel and tourist writers, radio and TV personnel and sales agents on familiarization tours of Israel during the winter months, and the benefits in increased tourism were reaped throughout the year.

Labor Unrest

The year 1960 saw EL AL turn its first annual profit following seven years of losses flying Constellations and making payments on the Britannias. With the introduction of the more efficient pure-jets in 1961, profitability started to soar, and for almost all the next 18 years (until 1979) EL AL operated in the black.

Inevitably, with financial stability, labor started demanding a larger share. Originally, an atmosphere of ‘one big family’ prevailed at EL AL, with a labor-management honeymoon. President Ben-Arzi, however, made it clear that he ran the airline and wanted no workers’ voice in management matters. In 1960 the pilots started the first strike, seeking higher wages and professional recognition, rather than receiving inferior treatment compared to foreign airmen. The next year the mechanics went on strike when 28 temporary employees were fired for creating labor problems. A bitter battle ensued, and EL AL aircraft had to be dispatched for a time by hastily mobilized superintendents and foremen. In 1962 the pilots struck again, with many angry charges and counter-charges. The following spring the first really disastrous labor walkout occurred when the airmen stopped flying during the peak Passover season. Each time EL AL was able to eventually settle the labor grievances. However, a pattern of labor disturbances emerged that continued to plague the airline for years to come and that adversely affected its competitive position.

Political Intrusion Fails

In 1962 the Israeli government pressured EL AL to open routes to West Africa. The government had been working hard to develop close political and economic ties to West Africa’s newly independent states, and it desired direct air routes to nurture this process. EL AL knew, however, that these routes could not be operated profitably and that having a profitable operation was one of the airline’s main policies and mandates. EL AL fought this attempted intrusion into its business, and the government backed down and allowed EL AL to continue to set route policy. Similarly, certain government officials, trying to curry favor with Belgium, The Netherlands and the Scandinavian countries, pressured EL AL to allow those countries to obtain greater market shares for Israel-bound passengers. EL AL complained that this would reduce its profits, and again the government eventually conceded. The principle of non-intervention by the state in the company’s daily business operations, established since the first days of the airline, was thereby maintained and reaffirmed.

Battling the Charters

Until the 1970s, international air fares on scheduled airlines were rigidly controlled by widespread government regulations and by the tariff system of the International Air Transport Association (IATA), of which EL AL and almost all major carriers were members. This cartel arrangement encouraged high and inflexible fares.

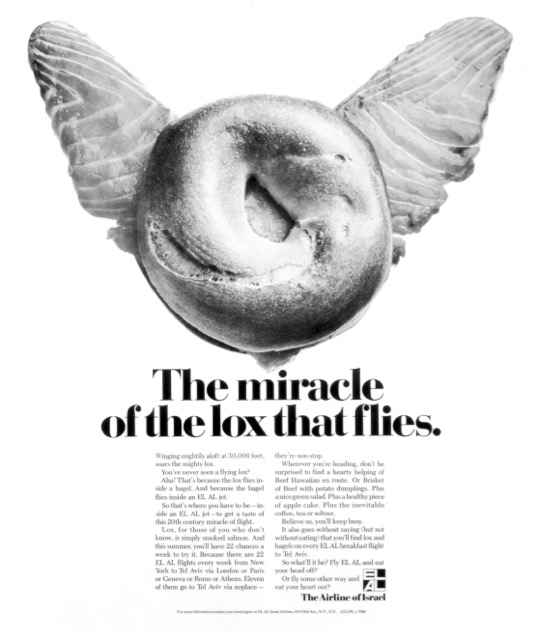

On the other hand, many resourceful non-scheduled airlines had arisen, spawned by the surplus of obsolescent equipment and the growth of tourism after World War II. Some charter airlines started US-regulated ‘affinity travel’ featuring significantly reduced fares for groups of individuals ostensibly having a common purpose, and their activities started to impact. In Europe, travel wholesalers began offering ‘inclusive tour’ packages with attractive prices geared to undercut scheduled operations and provide close to a 100% load factor. By 1958 40% of all passengers entering Israel came via special charter flights, a serious situation when about 90% of EL AL’s traffic was then tourist-oriented and only 10% business-motivated.

Mordechai Ben-Ari, EL AL’s commercial manager, fought repeatedly at IATA meetings for a more flexible international tariff structure and for better ways to combat the rise of charter traffic. Ben-Ari also made clear to the government EL AL’s early and forthright stand against the uninhibited growth of charters to Israel, arguing that the country needed a financially healthy national air carrier. EL AL could provide better and less expensive packages if the charter threat could be eliminated. Further, he argued, landing rights were a valuable commodity that should not be given away freely, and the charters would also undermine EL AL’s negotiating ability for wider overseas landing rights.

In 1961 EL AL negotiated a special resolution from IATA that allowed it, as a short-term approach, to offer affinity group fares. This filled some seats. However, the following year, Mordechai Ben-Ari, in a major contribution to EL AL and other scheduled airlines with a high tourist traffic component, tenaciously pushed through IATA a new concept—non-affinity group fares on scheduled flights. He reasoned that the scheduled airlines needed a lower, more flexible fare to promote mass tourism and defend against the charter operators. IATA demanded in return that all charter flights to Israel be banned, and in December 1962 EL AL succeeded in having the Israeli transport minister cancel all charters to and from Israel effective 1 April 1963. Non-affinity group rates were then introduced on scheduled services. However, this proved to be only a temporary victory, as the charter issue continued to resurface.

Only Seven Aircraft

During the early and mid-1960s EL AL carefully developed the practice of maximizing the utilization of each of its aircraft. In doing so, EL AL had to work with a very small fleet—only seven aircraft—to service a far-ranging network (from New York in the west to Teheran in the east, and south to Johannesburg); and it had to overcome limits on (and eventually the elimination of) passenger operations on the Jewish Sabbath and on certain Jewish holidays.

These restrictions notwithstanding, EL AL achieved one of the highest aircraft utilization rates in the industry. To illustrate, on a typical schedule for a single 720B during summer 1964, the aircraft would operate between 7am on Monday and 4:30pm Wednesday, Tel Aviv time, four roundtrips: to Zürich, Rome, Teheran and (via a European gateway) New York. During this 57½-hour period the aircraft accumulated about 40 hours flying time. It was then rolled into the hangar for an overnight maintenance check to be ready for an early flight the following morning.

Boeing 707s normally spent about 30 hours away from Tel Aviv on the New York run via Europe (except for the occasional nonstop flight). They typically would leave in the early morning and return the next day in the late afternoon for an overnight maintenance check before departing again on a similar schedule the following day.

EL AL’s aircraft utilization was such that it had a reserve aircraft factor of almost zero or, as one employee put it, ‘one-half an airplane for three days a week, and none for the remaining four’. During the Jewish Passover holiday in 1964, 707/720B utilization built up to an astonishing average of 15 hours per day. Nevertheless, EL AL still managed to maintain an enviable on-time record and high safety standards.

Maintenance and Technical Efficiency

A prime reason for EL AL’s high aircraft utilization has been its maintenance base. Gradually building its own capabilities, by 1964 EL AL handled almost all of its own airframe-electronics maintenance and overhaul work—tasks previously farmed out to Israel Aircraft Industries across the airport from the airline’s headquarters. The drive for self-sufficiency in maintenance was also spurred by the political conviction that EL AL always had to be ready to take care of itself, without the help of others, in the event of war or other emergency. In addition, striving for economy, EL AL was then hand-building the majority of its test equipment in its electronics, radio and overhaul shops, at considerable savings over what would have been foreign purchases. Maintenance checks came to be performed on an ‘equalized maintenance system’, at intervals of 100 hours and requiring 10-12 hours to complete, fitted into overnight hours. Each check would include all items due every 100 hours, a quarter of all 400-hour items, 1/6 of the 600-hour items, etc. This system permitted the basic operational pattern of scheduling the bulk of departures from Tel Aviv during the early morning so that the aircraft would return in the late evening, allowing the night-time period free for maintenance. In addition, an annual major overhaul, which would remove the aircraft from service for 12 days, was performed during the relatively slack four-month winter season.

The Fifth Pod

Engine overhauls in the early and mid-1960s, however, still had to be contracted out—to Rolls-Royce in England for the 707’s Conways and to SNECMA in France for the 720B’s JT3Ds. To accomplish this at minimum cost, EL AL adopted the ‘fifth pod’ procedure as a standard working tool. Designed by Boeing primarily as an ‘aircraft on ground’ procedure for ferrying engines, a pod was installed beneath the left wing of a 707, able to carry a powerplant in a streamlined shape akin to the aircraft’s regular engine nacelle. Conways were ferried to London and JT3Ds to Paris on regularly scheduled flights at almost no penalty in payload or performance. EL AL also modified the Boeing-designed kits for the two types of engines, cutting removal and installation time from the original three hours to an average of 35 minutes, the fastest of any airline. The schedule was thus unaffected by pod installation or removal.

Minimum Equipment Acquisition

One of EL AL’s original premises, nurtured by Ben-Arzi in the 1960s, was that its aircraft purchases should be restricted to manageable numbers. EL AL measured its needs by year-round requirements, not on peak seasonable demands which have traditionally been the Passover/Easter season and the summer months. During heavy traffic periods, therefore, additional aircraft would be leased or chartered. While many airlines practice this today, EL AL was one of the first to pursue it.

SST Flirtation

In 1964 deposits were made for two Boeing 2707 supersonic transports (SSTs), designed to fly over 2½ times the speed of sound. EL AL obtained preferred slots for production numbers 10 and 14 and a hoped-for early slice of the supersonic market. The SST would have cut the flying time between New York and Tel Aviv from nearly 11 hours (for the 707) to a little over five hours. EL AL opted for the US SST rather than the slightly slower and smaller European Concorde in part because EL AL could back away from its options and recoup the down payments made to assure production line positions. This was not possible under a Concorde contract. Perhaps more importantly, it correctly anticipated that the Concorde would not be able to fly the New York–Tel Aviv route nonstop. As it turned out, the Boeing SST was never built because of economic and environmental concerns. This was actually a fortunate development for EL AL and several other airlines which were still paying off the acquisition costs of an already modern fleet.

First All-Pure-Jet Airline in the Middle East

With the acquisition of two more Boeing 707s in 1965 and 1967, and the sale of the two remaining Britannias during the same period, EL AL became the first all-pure-jet airline in the Middle East. The fleet was still only seven aircraft, but it was a modern roster comprising five 707s (the original three Rolls-Royce-powered 420 series and two new Pratt & Whitney-powered 320Bs) and two 720Bs. The new 707-320Bs (like the 420 series) were not convertible to a full cargo configuration; however, they were chosen because they had the range that EL AL needed. In making this choice EL AL had to pass up, for the time being, 707 aircraft types that were capable of larger cargo capacity.

The Six-Day War

By May 1967 war clouds were once again gathering over the Middle East. Egypt’s President Nasser declared a blockade of Israel’s Red Sea port of Eilat, announcing that the hour of confrontation had arrived. Egyptian guns at Sharm-el-Sheikh, a coastal fortress overlooking the Strait of Tiran, were trained on Israeli shipping navigating this link with the Gulf of Eilat. The Soviet-equipped forces of Egypt’s army crossed the Suez Canal and began moving towards Israel’s Negev region. Egypt demanded that the United Nations forces in the Sinai evacuate their border positions, and the UN immediately complied.

Most of EL AL’s male employees under age 40, including more than half the aircrew, were mobilized. Despite being short of manpower EL AL was again called upon to undertake a unique task—the evacuation of thousands of innocent tourists in Israel before the deterioration of the situation into actual warfare. From 14-24 May 1967, with only a minimum number of aircrew available, EL AL transported 11,500 tourists from Israel.

Meanwhile, Israelis overseas and foreign volunteers mobbed EL AL offices desiring to travel to Israel to help in the anticipated defense effort. In Holland, young people camped on the streets while waiting for accommodations on EL AL flights. Later, there was a near riot in Amsterdam when someone spotted an EL AL airliner at Schiphol Airport. The young volunteers demanded seats and it took all the persuasion of EL AL personnel to convince them that the aircraft was in an all-cargo configuration.

EL AL also began to ferry military and other priority cargo to Israel, and aircraft were reported at such odd spots as the airfields of Dassault and Sud Aviation in France. So-called ‘undisclosed freight’ was picked up, although the airline was quick to point out that nothing outside the terms of normal insurance coverage was carried. During the airlift, crews were treated cordially; some were applauded at airport terminals, and air traffic controllers addressed flights with shalom—the traditional Hebrew greeting meaning ‘peace’.

At the time, EL AL had no pure cargo or convertible freighters. It was forced to make do by stripping the seats from aircraft outbound from Tel Aviv or, on some passenger flights, removing the seats at intermediate European points before picking up military and other cargo. Loading and unloading at Lod Airport were done by clerical and cabin staff and over-military age executives, pressed into service to replace the mobilized ground handlers. During evening hours they formed long lines and helped unload incoming aircraft. The critical maintenance schedule remained unchanged. Maximum aircraft utilization was achieved with daily use reaching 14 hours. The interiors of the Boeings became wrecks. Sharp-edged crates tore the linings out of cushions, shredded upholstery and mutilated decorative panels; carpeting was ruined by accumulations of mud and grime.

Employees worked 12-hour shifts—and many contributed even more hours–to make up for the absence of their mobilized colleagues. Essential offices never closed. Grounded stewardesses became drivers of minibuses, as the regular EL AL airport buses had been commandeered for the defense effort. Aircrews would fly ten hours straight and then return to flight duty after six-hour intervals, except for the pilots who were not allowed to exceed the legal limits of 10 hours per day or 120 hours per month. Somehow the airline still managed to fly scheduled routes. On 26 May 1967 The New York Times carried a two-page advertisement pointing to Israel’s crisis and summing up EL AL’s confidence that ‘We’ll be flying in 5728, 5729 [years on the Jewish calendar corresponding to 1968 and 1969]. In fact, we plan on flying there for a long, long time’.

In the early morning of 5 June 1967 war erupted between Israel and Egypt and Syria, later joined by Jordan. As in 1948 and 1956, all overseas airlines immediately stopped flying to Israel. Confronted by enemies on three sides and separated from the West by a sea on the remaining side, Israel was again cut off from the rest of the world—but for EL AL.

The airline’s first three flights on 5 June departed as scheduled, but to reduce risks it was quickly decided to operate in Israel only at night. Inbound aircraft that day and the next were delayed until nightfall, and departures were forbidden after daybreak. On the night of 5 June, all aircraft in EL AL’s fleet returned to Lod Airport and then departed. Turnarounds were made in near-record times, both to have departures before dawn and because of the tight schedule flown for government requirements. For takeoffs and landings the runway lights were switched on and normal procedures followed. Otherwise there was a complete blackout. The Avia Hotel, a few miles from the airport, was used as a terminal building so as not to expose the passengers to danger in case of air raids on the airport or shelling from Jordan. Several 155mm guns shelled the airport from beyond the hills on the Jordanian border on the night of 6 June, but fortunately caused little damage.

After 36 hours, when it became clear that Israeli air superiority had been established and daylight attacks on the airport were unlikely, morning and afternoon flights resumed, although still on a modified wartime schedule. With the outbreak of the war, passenger traffic from Israel came to a standstill, while in the opposite direction load factors soared under pressure by Israelis, foreign volunteers and newsmen traveling to the country. During the entire week of the war, EL AL remained the sole airline operating between Israel and the rest of the world.

Meanwhile, aircraft of EL AL’s then domestic subsidiary, Arkia, were also mobilized. Its 50-seat Handley Page Dart Heralds, first acquired in 1964, were converted to flying ambulances. On the outbound leg to the Sinai, the aircraft transported water in large cans to Israeli troops in the parched desert, landing at Egyptian air bases as these were captured. The return flights were made with wounded soldiers, both Israeli and Egyptian.

Many of the pilots of EL AL and Arkia were Israeli air force reservists, and they were drafted during the war to fly combat missions. EL AL lost four pilots and pilot trainees in action, including one captain; Arkia also lost one of its pilots.

Although Israel suffered many casualties, they were small compared to those sustained by the Arab forces. Within a handful of days Egypt, Jordan and Syria were pleading for a cease-fire, and after six days it was all over. Israel found itself in control of not only all the territory it held before the war, but also of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip to the southwest, the West Bank and East Jerusalem areas formerly occupied by Jordan, and the Golan Heights to the northeast that the Syrians had previously used as a high plateau from which to shell Israeli villages situated below in the Jordan Valley.

With all of Jerusalem in Israel’s hands and once again a united city, EL AL launched an intensive campaign, in cooperation with the Ministry of Tourism, to attract more visitors to Israel. Travel agents and writers were invited to see for themselves that Israel was a tourist attraction of high caliber. About two months later the tourist stream from abroad resumed, and it even continued through the winter. The phrase ‘off-season’, meaning the October to March period, almost vanished from the Israeli vocabulary as hotels found themselves filled winter as well as summer, and tourist figures reached an all-time high.

Arkia started new service to areas acquired in the war. These included Kalandia (Atarot) airport in Jerusalem, as well as service to the Sinai, including flights to Ophira (Sharm-el-Sheikh) and St. Catherine (Mt. Sinai).

Another significant development was the resumption of direct air service to Africa. On 12 June, only one day after the end of the Six Day War, at the initiative of EL AL’s Benjamin Davidai, a special test flight was made to Nairobi, Kenya, flying directly across the Sinai and south over the Red Sea — a route that had been denied to EL AL by hostile states since 1956. Davidai was aboard, with Zvi Tohar as Captain for the 4-1/2 hour flight. To everyone’s relief and excitement, It went unmolested, meaning that EL AL could now offer the most direct and shortest route from the West to the eastern and southern segments of Africa, placing Israel again in the crossroads between three continents. From 7 November 1968, using Boeing 720Bs and later 707-320Bs, EL AL flew direct via Nairobi to Johannesburg, now reached in a little more than eight hours, half the previous time taken via the circuitous route through Teheran.

Under New Management

The new wave of tourists planning trips to Israel to see the Western Wall and other sights of now-united Jerusalem gave rise to new conflicts on the issue of charter versus scheduled flights. Ben-Arzi (who had moved from president to chairman of the board in 1966 following a heart attack) and Col. Shlomo Lahat (who succeeded him as president) insisted that charters remain banned and refused any compromise. The Ministry of Tourism lobbied to permit charters, but EL AL won the battle (although with a few exceptions, mainly for Scandinavian flights). However, the strain of the political fight, as well as personal reasons, led both Ben-Arzi and Lahat to resign their positions in 1967.

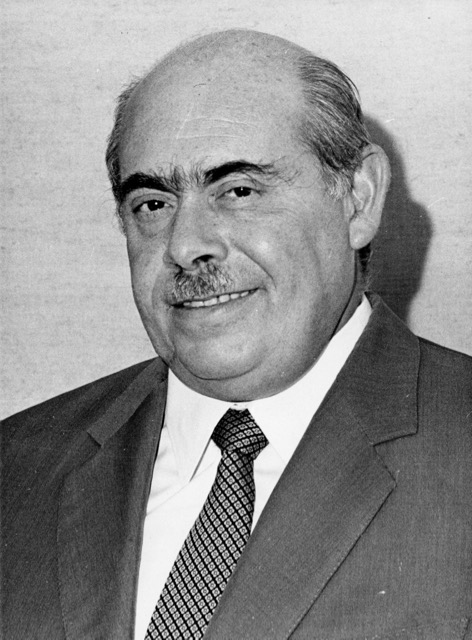

EL AL’s board of directors then elevated Mordechai Ben-Ari , its then Vice President-Commercial, to be President of the airline and in charge of marketing and finance, and promoted its Vice President-Operations Benjamin Davidai to be First Vice President, acting as the number 2 executive of the airline and the head of operations, aircraft and workforce.

Ben-Ari started with EL AL in 1950 and held successively higher managerial positions, being instrumental in the airline’s successful commercial development. During his tenure as EL AL president from 1967 through 1977, EL AL evolved from a small carrier into a significant, professional, globally respected airline. He strongly supported introduction of the jumbo Boeing 747 into the fleet as well as a substantial expansion of cargo. Ben-Ari was also a key participant at meetings and decisions of the International Air Traffic Association.

Benjamin Davidai served with EL AL from 1955 to 1976. He started out as an engineer and in Maintenance and achieved successive higher positions, becoming Vice President-Operations in 1963 and then First Vice President with expanded authority. He played a significant role in the introduction of the Britannias, 707s and 747s to EL AL’s fleet, and his key decisions during his tenure contributed greatly to EL AL’s operational efficiency and success.

With tourism to Israel expanding and a modern jet fleet, EL AL’s new president, Ben-Ari, looked forward to leading through a succession of profitable years. Under his able leadership EL AL would also smoothly enter the age of mass travel with the 747, but first there was a new challenge to face—the most dangerous of all.

Terrorism Rears Its Ugly Head

EL AL flight LY426, operated by its original 707 (4X-ATA), seemed perfectly routine as it took off from Rome’s Fiumicino Airport on 23 July 1968 for its return leg to Tel Aviv. Oded Arbarbanel, a veteran captain and one of the native-born Israeli pilots, was in command. The aircraft leveled off while still in Italy’s airspace. Suddenly, three passengers, actually Arab members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), jumped from their seats brandishing grenades and revolvers, forced their way into the cockpit, shot and wounded First Officer Maoz Poraz, and seized control of the aircraft. Grabbing the radio microphone from the captain, they agitatedly told Rome then Algiers air traffic control that the aircraft was now renamed ‘Al Jiddah 707’ and was being diverted to Algiers.

While there had been prior hijackings on other airlines, particularly to Cuba, nothing significant of the kind had occurred in the Middle East, and it caught EL AL and the aviation world completely by surprise. Little could be done once the 707 was commandeered, and it landed in Algiers. Israeli and international protests poured into Algeria, and many diplomatic initiatives ensued to release the hostages. Slowly but surely, groups of hostages, starting with the non-Israelis, were released. EL AL personnel were incarcerated the longest, and it was 40 days before the last of them, the male crewmembers, were freed on 1 September. Nor would the Algerians release the aircraft directly to EL AL. Eventually a French crew flew the 707 from Algiers to Rome, where EL AL took over and returned it to Israel. EL AL management and the Israeli government warned that this could be a harbinger of things to come, not only for Israel but all nations. But after the release of all the crew, world outrage subsided. While the specter of unlawful interference with commercial air transport loomed everywhere, the hijacking of the 707 still seemed minor.

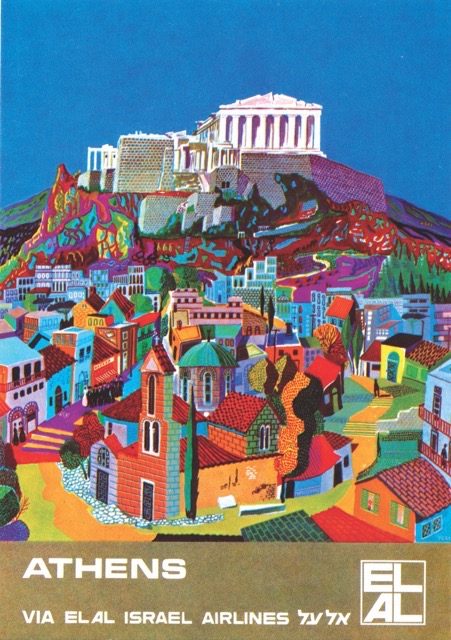

Attack at Athens

The Arab terrorists soon took a far more deadly tack. Less than four months after the Algerian hijacking ended, on 26 December 1968 an EL AL 707 (4X-ATR) was on the ramp at Athens, flanked by other aircraft and being serviced for a scheduled service to Paris and New York. On board was a crew of 10, plus 37 passengers. Meanwhile, a group of passengers was filing out of the airport transit lounge to an aircraft of another airline about 45m (50yd) from the EL AL airplane. Suddenly two young men broke away from the group and ran directly to the EL AL 707. One brandished a submachine gun and hand grenades. Firing as he ran, he pumped bullets into the aluminum skin of the aircraft until he was only a few feet away, piercing the nose and forward fuselage. A passenger in a window seat, a Haifa maritime engineer on loan to the United Nations, was killed instantly. Miraculously the crew and other passengers were not hit. Athens police finally overpowered the two terrorists, and the EL AL passengers were evacuated by emergency chutes and fled to the terminal building.

The PFLP proudly took responsibility for the attack, and Lebanese newspapers praised the attackers as heroes. Israel responded two days later with a lightning helicopter-borne reprisal raid, destroying 14 airliners of Arab carriers at Beirut International Airport, the jumping-off point for the terrorists. While the United Nations condemned Israel for using ‘excessive force’, Israel had made its point. It would not allow EL AL aircraft to be attacked and riddled with bullets while Arab airlines continued to fly with impunity.

Terrorists, broadcasting from Beirut and Damascus, made no secret of their plans to destroy the viability of EL AL. Their systematic program called for the creation of a web of fear that would frighten passengers away from the airline. Sudden, murderous attacks would undermine the morale of the airline, they reasoned, and cause serious damage to its aircraft and infrastructure.

But the terrorists miscalculated as to the resilience of EL AL and its president, Mordechai Ben-Ari. The airline swiftly organized a constant security alert and also appealed, through the Israeli government, to all nations enjoying reciprocal landing rights with Israel to give maximum protection to EL AL aircraft when under the jurisdiction of those governments. Through international civil aviation organizations it urged world-wide legislation against criminal attacks on commercial aircraft. EL AL introduced other security measures as well, but for the time being these were kept secret.

Zürich Airport Assault

On 18 February 1969, EL AL flight LY432, a 720B (4X-ABB) with 11 crew and 17 passengers, was taxiing to the runway for takeoff from Zürich’s Kloten Airport after a scheduled stop on an Amsterdam–Tel Aviv service. Four Arab terrorists were waiting near a fence at the edge of the taxiway. As the aircraft approached, they opened fire with several Kalishnikov submachine guns and hurled grenades. About 40 shots tore through the cockpit, killing Yoram Peres, a trainee pilot. Swiss police rushed to the scene, but not before Mordechai Rahamim, a supposed passenger on the aircraft, opened a door and started shooting back, killing one attacker before being taken into custody himself. In Amman, Jordan, the PFLP again took responsibility for the action.

Rahamim proved to be a security guard. EL AL had initiated the practice of having armed personnel on every flight. The airline was going to protect itself by whatever means available, and would not be a sitting target.

The passengers and other crewmembers were unhurt. All eventually continued to Israel with EL AL, and the 720B returned to Israel six days after the incident. Not only did the terrorist attacks not affect business, the airline actually continued to experience increased bookings both in Israel and in other parts of the world.

New Types of Terrorism

Frustrated at their unsuccessful attempts against EL AL, the Arab terrorists turned their attention to US airlines. On 29 August 1969 guerrillas hijacked a Trans World Airlines (TWA) 707 shortly after takeoff from Rome on a Los Angeles–Tel Aviv flight. The aircraft was diverted to Damascus, Syria, where the passengers were taken off and the aircraft severely damaged in a bomb explosion. Two Israeli passengers on board were incarcerated until 5 December.

The terrorists then switched to attacks on EL AL ticket offices. On 8 September 1969 they enticed two Arab teenagers to hurl two grenades into the Brussels office, injuring four people. On 27 September Arab youngsters lobbed grenades into the Athens office, injuring four members of a Greek family and killing one of their children. Attacks also occurred on EL AL offices in Istanbul and Teheran, but damage was inconsequential.

By 1970 police were patrolling EL AL offices on a round-the-clock basis, and airport authorities at all EL AL destinations started providing extra protection for the airline.

Trying yet another horrific approach, on 10 February 1970 at Munich-Riem, Arab terrorists attacked an airport bus carrying EL AL passengers, using automatic fire and grenades. Aryeh Katzenstein, a former paratrooper from Haifa, shielded the rest of the passengers from a grenade hurled through a window by absorbing the explosion with his own body. He died instantly. Uri Cohen, the captain of the flight, engaged one of the armed Arabs with his bare hands when the terrorist pulled the pin of a grenade and was about to throw it among the crowd of passengers and bystanders near the bus. Cohen was hurt in the struggle when the grenade exploded, but his action likely saved many lives. Meanwhile, passenger Hannah Meron, was badly injured.

On 6 September 1970 Arab terrorists attempted four simultaneous hijackings — against EL AL Flight 219 (707 4X-ATB) from Amsterdam to New York; Pan American 93 (a Boeing 747) from Amsterdam to New York via London; TWA 741 (a 707) from Tel Aviv via Frankfurt to New York; and Swissair 100 (a DC-8) from Zürich to New York.

When it was all over, the Pan Am, TWA and Swissair jetliners, plus a Vickers Super VC10 of British Overseas Airways Corporation which was hijacked three days later while operating a flight to from Bombay to London, lay in smoldering ruins, blown up by PFLP guerrillas at Cairo, Egypt, and Dawson Field, Jordan. The only one of the these flights to reach its destination safely was EL AL 219.

About 30 minutes after takeoff from Amsterdam, when EL AL 219 was over the North Sea, Arab terrorist Leila Khaled (who had been involved in the TWA hijacking of August 1969) and her male companion, Patrick Arguello, brandishing revolvers and grenades, rushed to the cockpit door in an attempt to take over the 707. They pinned a stewardess next to the reinforced door, threatening to kill her unless it was opened. The cockpit pilots, Capt. Uri Bar-Lev and First Officer Arie Oz, quickly sensed there was only one way to save the aircraft and passengers. They thrust the 707 into a steep dive, and this maneuver threw the hijackers off balance. Passenger Simon Super and a steward charged Khaled and pinned her down. One of her grenades rolled to the floor but miraculously did not go off. Arguello shot another steward, Shlomo Vider, then was himself killed by gunfire from an EL AL security officer. The EL AL captain then diverted the aircraft to nearby London-Heathrow, and although this meant having to turn Khaled over to British authorities (and she was soon released under pressure in exchange for hostages from the hijacked London-bound VC10), the quick landing helped save Vider’s life. As in the previous terrorist attempts, the mass hijackings of September 1970 ultimately served to reinforce EL AL’s reputation for security.

Reverting to other methods, on 30 May 1972, three Japanese Red Army terrorists, recruited and then trained in Lebanon by the PFLP, attacked Tel Aviv’s Lod Airport and disembarking EL AL passengers with machine guns and grenades, killing 24 persons, including 16 Christian pilgrims from Puerto Rico, and wounding nearly 80, including EL AL stewardess Antonia Zaharia Deutsch. On 20 August 1978, terrorists ambushed a bus carrying EL AL personnel to their hotel in London, killing EL AL flight attendant Irit Gidron and wounding nine including flight attendant Judith Arnon. And on 2 January 1980 in Istanbul, terrorists followed and killed EL AL local station manager Abraham Elazar when he was driving home after completing work and dispatching a flight to Tel Aviv.

Nevertheless, all these attacks, among others, failed in their purpose to disrupt EL AL and strangle travel to Israel. Instead, both Jews and non-Jews demonstrated a strong feeling of solidarity with Israel’s national airline, and EL AL continued to attract ever-increasing numbers of tourists and operate profitably, while discouraging renewed terrorist attempts. Over the years the importance and sophistication of EL AL security has further grown and is recognized as the best in the industry (see Chapter 10).

Cargo Expansion

Towards the end of the 1960s, spurred by president Ben-Ari’s conviction that EL AL could greatly expand its cargo operations, EL AL identified prime cargo market opportunities on its trans-Atlantic route. Accordingly, in 1969 and 1970 it acquired two 707-320Cs (4X-ATX and 4X-ATY), convertible cargo/passenger models. Each could carry 37,800kg (42 tons) of cargo in bulk or 34,200kg (38 tons) on pallets. These, together with the addition of a third 707-320B passenger aircraft in January 1969, brought EL AL’s fleet to 10: eight 707s and two 720Bs.

Using its first 707-320C, the initial all-cargo jet flight from Tel Aviv to New York operated, via Paris, on 28 September 1969, and the schedule quickly grew to four such flights each week to Europe and the US. In three years, 1969-72, EL AL’s air cargo traffic doubled. This expansion, together with flexible air cargo rates negotiated for specific commodities, stimulated the growth of exports from Israel of agricultural products, textiles, fashion garments, and fruits and flowers.

New Routes

In April 1968 EL AL inaugurated scheduled service to Geneva, Switzerland, and Nice, France (the latter destination was replaced by Marseille in March 1971). Four months later, in August, it added Romania to the network. Pending completion of a new airport at Bucharest, EL AL initially flew to Constanta on the Black Sea coast. Bucharest was a particularly important destination for EL AL and Israel as it was their only window at the time to the East European Communist Bloc.

Service began to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in April 1970, although this route was terminated by the Ethiopian government under Arab pressure shortly after the October 1973 Yom Kippur War.

The Pinnacle of 707 Service

By 1970 daily average utilization of the fleet was an exceptionally high 12 hours. Considering that EL AL was then operating only 306 days a year because of the constraints of flying on the Jewish Sabbath and holy days, this translated into an actual utilization of nearly 15 hours per day. All aircraft were active during the April-October high season. Between October and March, one of the 10 Boeings would undergo a major overhaul.

The number of employees grew to nearly 4,000 by the end of 1970, including 64 flight crews, and about 90% of the staff were Israeli nationals. Pilots were typically recruited directly out of one of the finest training centers in the world—the Israeli Air Force. The average age at which pilots would make captain fell to 30, among the youngest in the industry. By early 1971 the 707s and 720Bs had served EL AL faithfully and safely for almost 10 years. They became the proud symbol of an airline that continued to gain acceptance as one of the most efficient in the world. Soon, however, these aircraft, like their predecessors, would have to relinquish their position of eminence. Already industry leader Pan Am and other major airlines had entered a new era—that of the wide-body Boeing 747. EL AL would not be far behind.

Last updated 7 July 2021.

Copyright 2021, Marvin G. Goldman