Your children shall come back to their own country (Jeremiah 31:17)

Operation Exodus

Although EL AL had been famous for its many airlifts of Jewish immigrants to Israel, from Yemen, Iraq and elsewhere, nothing compared in numbers to Operation Exodus—the airlift of Soviet Jews in the 1990s.

For two decades the desire of Soviet Jews to immigrate to Israel had increasingly stirred. Each year during the 1970s and 1980s, however, only a few hundred or a few thousand could exit, with several coming to Israel aboard special EL AL flights, at first typically through Vienna, Austria. In 1988/89, through EL AL’s eastern European link to Bucharest, Romania, and with new routes opened to Budapest, Hungary, and Warsaw, Poland, a few thousand arrived.

The rise and high point of the largest mass immigration in Israel’s history came as the Soviet Union significantly loosened its emigration policy. In 1990, over 185,000 Jews came to Israel from the Soviet Union, typically transiting through other countries. That year EL AL flew in 120,000 immigrants, the vast majority from the Soviet Union, as well as others originating from other eastern European countries and even Ethiopia.

Continuing with EL AL’s tradition of helping those in need, president Rafi Harlev pledged to the Israeli government that the airline would operate a flight at any time to carry immigrants to Israel from anywhere within 12 hours notice.

By late 1990, EL AL was operating up to 20 flights per week from Bucharest alone carrying Soviet Jews to Israel. The immigrants would arrive in Romania by train from Kishinev, Moldova, and Kiev, Ukraine. Often they were processed and en route to Israel within the same day. If they stayed overnight at a hotel arranged by the Jewish Agency, suitcases were checked at the hotel and transferred directly to the aircraft.

Towards the end of 1990, after prolonged negotiations, EL AL reached an agreement with the Soviet government and Aeroflot, allowing charter flights by both airlines between Moscow and Israel. EL AL began such flights in January 1991. This contributed greatly to the total of another 148,000 immigrants to Israel from the Soviet Union in 1991. With the breakup of the Soviet empire at the end of that year, EL AL added destinations in the newly created states, thereby broadening its airlift. Operation Exodus continued throughout the 1990s, with the total number of immigrants to Israel from the former Soviet Union during that decade reaching 860,000—a large portion of whom arrived by EL AL.

On board many of these flights the new arrivals were welcomed with a Russian-language video, produced by EL AL to help them assimilate into life in Israel, in which veteran immigrants related their experiences. A new in-flight magazine, printed in Russian, Hebrew and English, was also introduced.

The Gulf War: Flying While Evading Scuds

On 2 August 1990, Iraq invaded oil-rich Kuwait, claiming that country was Iraqi territory. Reacting to the move, several United Nations Security Council members imposed economic sanctions on Iraq, and moved military forces to the general area. On 29 November the Security Council gave Iraq an ultimatum—withdraw by 15 January or confront armed force. Meanwhile, Iraq’s Saddam Hussein escalated his threats to launch missiles against Israel in the event anyone attacked his country.

The prospect of all-out war created a tourism crisis in Israel. Between September and December 1990, compared to the same period a year before, visitors declined by nearly 50%. Aviation fuel prices jumped 120% in a short period. EL AL responded, as it had in 1988, by slashing expenses wherever possible. Capacity was reduced by 30%, although frequency was maintained on major nonstop routes to North America and Europe. Many temporary employees were laid off and permanent staff given vacation leave. As Harlev said, “The key thing was to make decisions as early as possible and make no mistakes”.

As the January deadline drew near, and threats of Iraqi missile and chemical attacks on Israel loomed, embassies in Israel evacuated staff, and foreign residents streamed out of the country. Some Israelis, not wanting to be sitting targets for Saddam Hussein’s missiles, started to leave. Yet at the same time others, living overseas, chose to return to their native land and share the fate of their compatriots. Meanwhile, immigrants from the Soviet Union and eastern Europe continued to arrive.

Overseas airlines canceled services to Israel after insurance companies levied steep increases on aircraft and persons flying to Israel, rendering flights unprofitable. By 13 January only Tower Air of the United States maintained a presence, operating two flights a week from Tel Aviv to New York (although there was no traffic inbound). EL AL once again became the sole air link in both directions between Israel and the rest of the world. One of the leading newspapers in Israel, Maariv, summed up the general pride felt for the national carrier with the headline: ‘Israel’s skies are blue and white only’.

Israeli families prepared special ‘sealed rooms’ with plastic sheeting and duct tape and were issued protective clothing and gas masks in anticipation of Iraqi missile attacks. Iraq had used chemical weapons in the past, and there was widespread fear that projectiles would contain deadly gas and other agents. Demand soared for emergency and consumer items, such as radios, videos, batteries and food stocks. To meet this need, as well as handle increased exports, EL AL converted a passenger 747 (4X-AXB) and two 747 combis to freighters.

The deadline passed without Iraq withdrawing its troops from Kuwait, and on 17 January coalition forces led by the United States attacked Iraq. Israel braced for the worst, and a day later Tel Aviv and Haifa were hit by ballistic missiles fired from western Iraq. By attacking Israel, Saddam Hussein hoped to provoke retaliation that would antagonize the Arab members of the US-led coalition. Israel sought to retaliate, but was restrained.

Over the next few weeks more than 40 missiles, known by their NATO reporting name of ‘Scud’, were fired at Israel, with one direct fatality, 15 related deaths, many wounded and substantial property damage. Defensive Raytheon Patriot anti-ballistic missiles, supplied by the US, had only limited success.

During this grim period, EL AL continued to soar to the skies, taking out foreign residents as well as Israelis, including all passengers whose reservations on other airlines had been canceled. Thousands of returning Israelis, participants in solidarity missions, overseas Jews with families in Israel, business travelers and new immigrants from the Soviet Union and Ethiopia were brought in. Arriving passengers received gas masks, and those departing left theirs with ground hostesses at the gates. On 17 January alone, four Operation Exodus flights arrived, from Budapest, Warsaw and Bucharest, transporting nearly 1,000 Jews from the Soviet Union (as well as 100 Ethiopians) to their new homeland. During that month, some 15,000 immigrants were brought to Israel. At the same time, commercial service was maintained. On 18 January, six flights were operated to Europe. EL AL’s media proclaimed ‘Now’s the time to fly together’.

Confronted with the missile danger, EL AL established emergency and sealed rooms at Ben-Gurion Airport. Airplanes remained overnight abroad, and flight paths to and from Ben-Gurion Airport were changed to avoid overflying Tel Aviv. As about 80% of the Scuds were fired at night, almost no flights arrived after sunset. Incoming aircraft, after circling and receiving the all-clear from air traffic control, would land in the late morning or early afternoon. Aircraft would spend the minimum time on the ground, between 45 and 60 minutes, then depart as soon as possible. This was contrary to EL AL’s usual timetable whereby most flights departed in the morning and arrived in the afternoon and evening.

Freight was offloaded and loaded in as little as one hour, and employees worked under intense pressure, at all hours, with heavy loads and with many items requiring special care.

The first two weeks of the war continued to dictate great flexibility in dealing with heavy bookings and demanding clients, accommodating passengers holding tickets on other airlines, scheduling and rescheduling, and arranging continuous work hours when most Israelis were retreating to sealed rooms at home after dark. Ironically, because EL AL had a temporary monopoly on air traffic, in January 1991 it experienced a complete turnaround from the preceding five months, and total traffic including immigrants was 5% over the corresponding month the previous year.

Starting in early February, a semblance of a new schedule was introduced for 40 days to facilitate reservations and sales, and by mid-February traffic began to rebound, with Israelis returning home, and the usual balance between incoming and outgoing traffic resumed. On 28 February the coalition forces and Iraq declared a ceasefire, and all air operations to Israel returned to normal. EL AL could take pride in surviving another crisis through strenuous efforts.

Operation Solomon

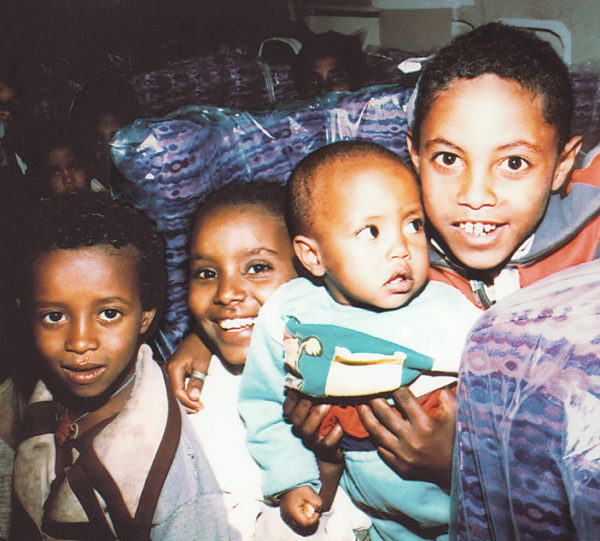

Black Jews have lived in northern Ethiopia for 2,000 years. Considering themselves descendants of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, and cut off from outside contact, they followed many ancient Jewish traditions and for centuries believed they were the only living survivors of the former Kingdom of Israel. Starting in the 1970s their serious economic plight attracted international attention, and in 1984-85 about 8,000 were brought to Israel via arduous overland escape routes through the Sudan and a clandestine airlift called Operation Moses, in which EL AL participated by carrying them from European transit points to Israel. Ethiopia and Sudan had no diplomatic relations with Israel at the time, and the airlift was halted after premature publicity.

In 1989, diplomatic relations between Ethiopia and Israel were restored, and efforts to rescue the remaining Ethiopian Jews accelerated. Operation Solomon was conceived in early 1990 with the decision to encourage their relocation from peasant-like villages in northern Ethiopia to the capital city of Addis Ababa, in the hope of airlifting them directly to Israel. Over 14,000 of the remaining 20,000 Ethiopian Jews moved to Addis Ababa, to refugee compounds where they were housed and fed by Israelis and international Jewish organizations. However, the reigning Ethiopian dictator, President Mengistu, treated the Jews like political pawns, with exorbitant demands for military arms and aid from Israel in exchange for releasing a few Ethiopians at a time, so he could better fight his long-standing civil war.

By May 1991, all of Ethiopia was on the verge of takeover by rebel forces. Fear spread that the civil war would quickly reach Addis Ababa itself and wreak havoc on the clustered Jews. Feverish negotiations led by Israeli Uri Lubrani pressed Mengistu to authorize the airlift, but on 21 May Mengistu suddenly fled the country to save his own life. The Israelis then negotiated with both the successor government and the rebels. Finally, a deal was struck, with the Israelis making a $35 million ‘facilitating payment’ to the Ethiopian government and agreeing that the airlift would be completed in three days.

On the morning of Friday, 24 May, the Ethiopian Jews in Addis Ababa were informed of the airlift. They had to leave all their belongings behind except the clothes on their backs and what they could stuff into a small bag. Many came barefoot. Two-thirds were under age 18. They were taken to the Israeli embassy in Addis Ababa for processing and then transported in numbered groups direct to the military section of the international airport.

Meanwhile, at Ben-Gurion Airport that morning, several EL AL airplanes awaited. The airline’s name on the fuselage and the Israeli flag on each tail were painted over to downplay the Israeli connection. Although EL AL was accustomed to airlift operations, none had ever involved moving so many people in so short a time. EL AL carefully prepared for months, coordinating with the commander of the operation, Amnon Lipkin-Shahak, then deputy chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces, while EL AL Vice President Reuven Virovnik coordinated ground operations in Addis Ababa. Some 300 ground workers, pilots and flight attendants were now at Ben-Gurion, ready to work around the clock. A select group of 25 ground and operational personnel flew into Addis Ababa to coordinate flight operations. Because the airlift began on a Friday, it was known that it would continue into Friday night and Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, when EL AL does not normally operate. However, Jewish law and the Israeli Rabbinate gave special dispensation to conduct the rescue airlift in order to save lives.

A Boeing 747-200C (4X-AXF) was the first aircraft to depart on the rescue operation, lifting off from Tel Aviv at 1258 PM on Friday, the 24th. Previously used for cargo, the 747 had been converted to passenger configuration within 24 hours. By using a 29in (74cm) pitch, and having no galleys and only four toilets, no less than 760 seats were installed.

The captain was EL AL’s flight director for the airlift, Arie Oz. During the 1960s Oz had been the personal pilot of Ethiopian ruler Haile Selassie. Also, in 1976 he had been the first pilot to land in Entebbe, Uganda, when Israel rescued the hostages of an Air France flight that had been hijacked by terrorists.

As the Ethiopian Jews waited calmly at Addis Ababa Airport, guarded by Israeli security officers, the Ethiopian government and the rebel forces adhered to their agreement not to intervene, even though their respective armed troops were only 2km (1.2mi) apart from one another at the capital.

The 747 covered the 2,575km (1,600mi) from Tel Aviv to Addis Ababa in 3hr 15min. Countries en route had been notified of the operation and its peaceful, humanitarian mission. Upon landing, streams of waiting refugees were quickly boarded. Up to six persons were crammed into each bank of four seats in the center of the 747, and up to four were fitted into each bank of three seats on the sides, in this magnified repeat of the ‘high density immigrant seating’ once employed in the Yemenite airlift. “Weight was not a problem”, said Captain Oz, “these people are very light”.

Previous Ethiopian immigrants to Israel helped with the flights and conversed in Amharic with the astonished newcomers. Medics and armed guards were also aboard. Only bottled water and rolls were made available for passenger ‘meals’. An advertisement that ran after the airlift proclaimed ‘Just for once EL AL decided to put comfort last’.

When the 747 took off for Tel Aviv the registered head count was an astonishing 1,087 passengers, a record—that still stands—for the most people carried in an aircraft. Capt. Oz later said that in fact there were 1,122 persons aboard because of non-counted babies concealed in scarves and robes of their mothers.

EL AL made 11 airlift flights, bringing in nearly half of the some 14,000 immigrants, with at least one baby born en route. The first three flights were by 747s; however, the runway at Addis Ababa was in poor condition, with an unsettling curvature, and was also of insufficient length and strength. So the remaining flights were operated with 767 and 757 twin-jets. Other trips were flown by the Israeli Air Force with Boeing 707 and Lockheed C-130 Hercules aircraft, and Ethiopian Airlines made one 757 flight. At one point, more than a dozen aircraft were in the air between Ethiopia and Israel. None of the Israeli Air Force aircraft had seats, and refugees aboard them had to sit on the floor or on mattresses.

The high altitude of Addis Ababa airport, some 2,300m (7,700ft) above sea level, required careful performance considerations, but did not prevent any of the types involved from setting new records for numbers of passengers carried. One 767-200 (4X-EAB) carried 430, and one 757-200 (4X-EBR) carried 360. Up to 400 people were carried on an Israeli Air Force 707.

At Ben-Gurion Airport and an adjacent military airfield, the immigrants walked, hobbled or were carried down the aircraft stairs. Many were in flowing robes, with only the humble possessions they could carry. Some knelt and kissed the ground of the land of their dreams. Joyful reunions occurred between husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, and sons and daughters, who had been brought to Israel in the earlier airlifts.

By noon Saturday morning, the last Israeli transport left Addis Ababa for Tel Aviv. An hour later, Ethiopian Airlines announced it was closing operations at Addis Ababa because the rebels were entering the city. On the very next day the rebels captured the airport. In Israel, the Ethiopian Jews were safe in their new homeland.

Fate Is the Hunter

On the afternoon of Sunday, 4 October 1992, 747-200F (4X-AXG) arrived at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport as Flight 1862 from New York-JFK. The new crew for the next leg of the freighter service to Tel Aviv were Captain Yitzhak Fuchs, a highly regarded EL AL pilot for 21 years, First Officer Ohad Arnon, and Flight Engineer Gedalyah Sofer. A sole passenger, Anat Solomon, wife of an EL AL security officer in Amsterdam, also boarded.

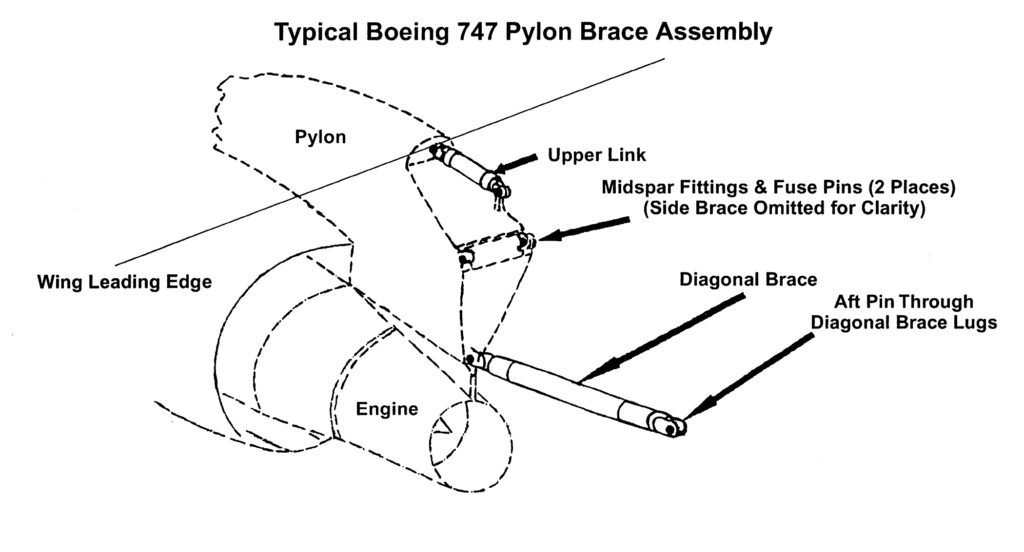

Six minutes after takeoff, at 1827, as the aircraft climbed through 6,500ft (1,980m), the instrument panel displayed a fire warning for the N° 3 Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7J turbofan, the inboard engine on the right wing, and there was a loss of engine thrust on both N° 3 and 4 (the outboard JT9D on the same wing). Fuchs declared an emergency to Dutch Air Traffic Control, requesting the quickest possible approach to return to Schiphol.

Unknown to the crew, the N° 3 engine and the pylon holding it to the wing had torn off—the fuse pins securing them having failed. The fuse pins are designed to shear in extreme conditions, such as a sudden engine stoppage, allowing the powerplant to drop safely away from the airframe. However, as fate would have it, the separated JT9D collided into the N° 4 engine, tearing that off as well and damaging the leading edge of the right wing. Because the engines and wings on a 747 are not visible from the flightdeck, the crew had no knowledge of this either.

During the descent, the crew reported that, besides the complete loss of power from two engines, they were experiencing severe control difficulties. While reducing speed during the approach, all control over the 747 was lost at 1833, and three minutes later the aircraft crashed into an 11-story apartment building in the Bijlmermeer suburb of Amsterdam. In addition to the three crew and sole passenger on board, 39 on the ground were killed. Many others were injured—most of them residents of the stricken building who had immigrated to Holland from Ghana and the Netherlands Antilles. The Dutch and Israeli governments, as well as EL AL, each set up an investigation committee. Slowly but surely the facts were pieced together. The reports concluded that the failure of the fuse pins, probably through corrosion and metal fatigue, was the primary cause. A very similar crash of a China Airlines 747F the year before was now fully understood, too. In that accident, the same two engines had also fallen off, with similarly disastrous results. Boeing and aviation authorities immediately ordered the replacement of all fuse pins on 747s powered by Pratt & Whitney and Rolls-Royce engines and, finding that previous directives to ensure structural integrity by examination were inadequate, specified a more intensive and frequent inspection program for all operators.

EL AL’s investigative committee, headed by Capt. Arie Oz, himself a Dutchman by birth, further pointed out that during the fateful minutes when the crew tried to land, there was a recording (also transcribed in the Dutch investigative report) of a Dutch coast guard ship which advised local Air Traffic Control that an engine had fallen from the 747. This information was not passed to the EL AL crew. Had the crew been so advised, then instead of believing the instruments’ indication of engine fire (which caused them to follow the accepted procedure in such cases of trying to land as soon as possible while maintaining as high a speed as possible), they could have taken different actions, such as selecting a different runway, that might have resulted in a safe landing.

The EL AL report also criticized Boeing for reacting slowly and ineffectively to the China Airlines accident.

A state funeral was held for the three cockpit crew, who were buried side by side in Kiryat Shaul cemetery in Tel Aviv. EL AL made compensation payments to the families of all the crash victims and established the Red-White-Blue Park near Beersheva, Israel, as a memorial. The airline also reached a settlement with Boeing that included arrangements for a replacement freighter.

Although the principal cause of the crash was unanimously agreed upon, the Dutch inquiry proceeded further due to claims by survivors on the ground that they were suffering respiratory and various other health problems. The Dutch claimed there may have been dangerous cargo on the 747 and that gaps existed in the documentation concerning the nature of the goods. Eventually, however, the necessary paperwork was assembled to prove that no hazardous materials were on board.

The accident remains one of the saddest episodes in EL AL’s history.

New Destinations: The Heart Soars

With the collapse of the Soviet bloc, air links could be strengthened and in 1990 EL AL increased frequencies to Budapest and Warsaw. Scheduled service to Berlin was added on 4 September 1990, followed by Prague on 25 June 1991. Regular charter flights started to Moscow (January 1991), St Petersburg (December 1991), Tashkent, Uzbekistan (January 1992), and Minsk, Belarus (November 1993). In western Europe, scheduled service began to Barcelona, Spain (March 1993) and Milan, Italy (April 1995).

The Far East Calls

For several years EL AL had desired a route to the Far East. During April-May 1992 it operated a series of six charter flights from Japan (the first being from Nagoya) to Israel, bringing more than 1,200 Japanese tourists to the country.

Meanwhile, extended negotiations with the Chinese finally bore fruit with the signing of an air agreement in July 1992. From 4 September that year, EL AL began a weekly 8hr 40min nonstop service to Beijing, routing over Tashkent.

Other schedules to Asia followed—Mumbai (Bombay), India, and Bangkok, Thailand (9 December 1993); Hong Kong (5 October 1994); and New Delhi, India (9 January 1995). All were successful. They also helped balance seasonal traffic differences, as the peak demand for these destinations generally came during the colder months.

North American Expansion

In 1989 EL AL entered into a cooperation agreement with North American Airlines (NAA), with an option to purchase a 24.9% interest in the new United States air carrier. NAA was majority owned by Dan McKinnon, formerly head of the US Civil Aeronautics Board. Originally, the start-up’s main purpose was to operate feeder flights to New York-JFK, EL AL’s main US gateway. NAA flew smaller aircraft, such as 757s, saving EL AL the cost of operating larger 747s between New York and other US cities, such as Los Angeles and Miami, at uneconomical load factors. (As other overseas airlines, EL AL does not have cabotage rights in the US, that is the right to carry passengers whose travel begins and ends in the U.S.). This in turn freed the 747s for more productive service elsewhere. EL AL guaranteed taking a minimum number of seats on NAA flights.

The first NAA/EL AL service, initially on a twice-weekly frequency, occurred on 22 January 1990, between New York and Los Angeles. NAA employed US crews, but at least one EL AL flight attendant was on board, and the Israeli airline provided all the ground handling, catering and dispatch services at both airports.

Later in 1990 EL AL exercised its stock option, and the shareholding was held until July 2003 when it was sold to McKinnon. Meanwhile, NAA also operated from Miami to JFK on behalf of EL AL, as well as from Baltimore/Washington International Airport and Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas, for a brief period starting in 1992. Following the purchase of new 747-400s, EL AL added three new US gateway cities in 1995 for nonstop service to and from Tel Aviv: Newark, New Jersey (its second in the New York area, on 28 March), Miami (23 June) and Los Angeles, California (24 June). Although service to Miami and Los Angeles became one-stop for a few years, nonstop service resumed in March and July 2006, respectively. The latter route became EL AL’s longest, and when started it was the longest in the world. From Tel Aviv to Los Angeles the average flight time is 14 hr 30 min. Like any flight over 8½ hours, it carries a second crew. With a full load of 408 passengers, plus cargo, the 747-400 typically weighs about 394 tons, including a fuel load of 160 tons.

More New Aircraft for European Routes

Four more new Boeing 757-200 Extended Range (ER) aircraft were acquired for European routes, bringing the 757 fleet to seven. These additions comprised 4X-EBS/T/U/V, delivered between November 1990 and May 1993. In December 1992 EL AL grounded the last of its 707s (4X-ATX), which had been operating in its final months as a freighter. This marked the end of 31 years with the type.

Innovation

EL AL’s reputation for technical innovation continued during this period. In fall 1990, a 747-200B passenger aircraft (4X-AXB) was converted to a freighter. The project was the first of its kind. It arose as a direct outcome of the Persian Gulf crisis with Iraq, which had led to sharply increased fuel costs and fewer passengers for EL AL, but more demand for cargo capacity. The work was carried out in two weeks at minimal cost and with no structural changes to the airframe. With EL AL ingenuity, mini-pallets were developed for maneuvering on skids through the regular passenger doors. Instead of the 29-pallet capacity of the 747-200F, 67 ‘Zvi’ pallets (named after the employee who developed the idea) could be carried. Although the conversion was payload-limited to 70-90 tons (compared to 97-130 tons for a regular freighter) and was operated only to London and Amsterdam because of the non-standard loading procedures, it still contributed great value.

Another innovation was the ‘the dock’, an elaborate, flexible structure which could be maneuvered and adjusted to surround the entire sides and rear of any of its aircraft, facilitating access for servicing.

In 1990 and 1991 EL AL installed additional fuel tanks and further modified its 767-200s to upgrade them to ER (Extended Range) standard. For the first time this work was done in-house, not by Boeing. The change permitted nonstop operations to North America, enhancing the flexibility to react to traffic demands.

EL AL introduced ‘Carmel 2’, a new CRS (computer reservation system) on 15 March 1990. This followed a painstaking selection process and 18 months of intensive training and other preparation. Installed in EL AL branches and travel agencies around the world, it greatly improved the fare quotation system, ticketing, seat selection and other customer service aspects.

As early as 1991, EL AL began to install TCAS (Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System) on its aircraft, starting with a 747. TCAS is a computerized avionics device designed to reduce the danger of mid-air collisions. Surrounding airspace is monitored for other aircraft equipped with a corresponding active transponder, independent of air traffic control, and pilots are warned of any potential conflicts.

Service

As Israel’s economy developed, through innovations in technology and other fields, the demand for business-related travel significantly increased from 1990. In response, EL AL expanded business class on 747s serving the USA, from 34 to 64 seats, and King David Club lounges at Ben-Gurion and JFK were refurbished in 1991 and 1992, respectively.

By summer 1993, 1,800 new coach seats were installed on trans-Atlantic 747-200s, offering an extra 2.75in (7cm) of legroom for each passenger. Larger overhead storage bins, new electronic stereo headsets and more video monitors also formed part of this multi-million-dollar renovation.

1993 also marked a new emphasis on customer satisfaction. Marketing materials echoed the theme, introducing the slogan ‘EL AL with all our heart’.

Television spots in Israel emphasized ‘How good it is to come home’, and a new ad campaign featured ‘Come to the only airline that takes you to its heart—EL AL’. A February 1994 letter from Harlev to all employees stated that all must emphasize service, going to the heart of the customer, so that they’ll come back and select EL AL. Service must be improved not just with smiles, but with actions. “Without you, we cannot accomplish anything. With you, we can do everything”.

The years 1994 and 1995, however, highlighted that EL AL had not adjusted quickly enough to the expectations of business travelers and the growing competition from other airlines. In its push to achieving profits through the most efficient aircraft utilization, flights sometimes were canceled without notice or the aircraft type would be suddenly changed, while other flights would unexpectedly be combined with other sectors or simply rescheduled. This even occasionally included the insertion of intermediate stops on the prime nonstop route between Israel and the US. These ‘flexible’ flight operations often created serious problems for customers, and the complaints and loss of loyal travelers increased.

This situation became worse when the first two 747-400s delivered in 1994 were fitted with many more seats in each class compared to other airlines flying to Israel. Complaints mounted, and finally the cabin layout was changed to a competitive level. The third 747-400 was delivered in 1995 with this revised configuration.

Eventually the lesson was learned. EL AL ultimately changed its flight operation policies and greatly enhanced its product, as will be seen in the next two chapters.

Enter the Super Jumbo

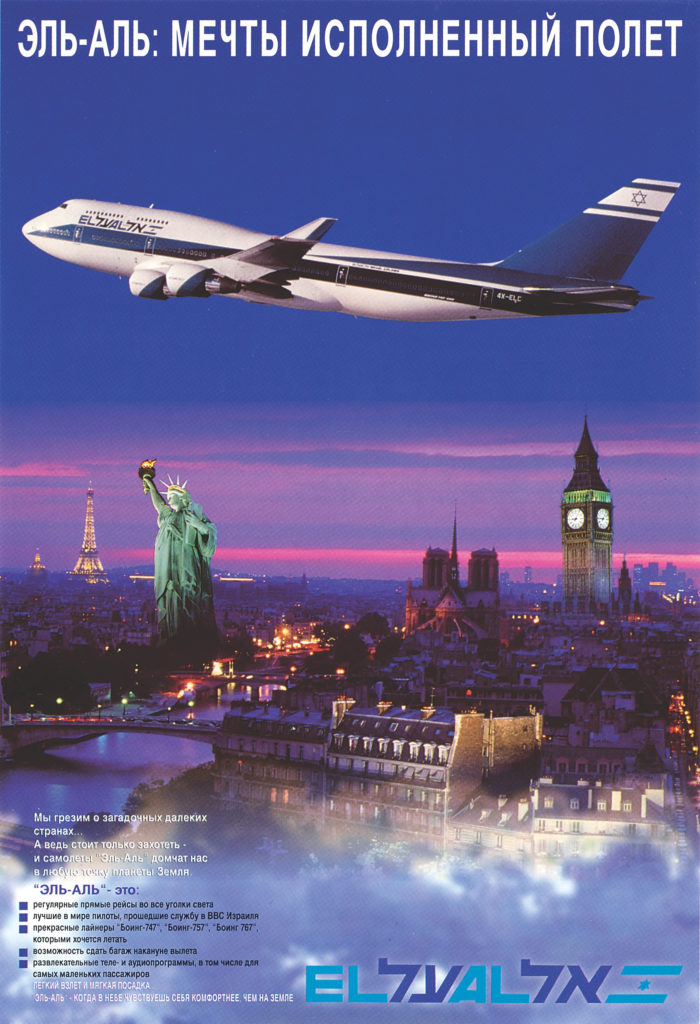

In April and May 1994 EL AL acquired its first two 747-400s (4X-ELA and 4X-ELB), and in June 1995 it acquired a third (4X-ELC). These became the flagships of the fleet. The Dash 400 model featured many improvements. More powerful Pratt & Whitney PW4000 engines offered 14% less fuel burn, lower exhaust emissions and half the noise level of the original JT9D turbofan. Maximum takeoff weight increased by 32 tons, to about 425 tons. Aircraft systems were upgraded, including the flightdeck, which has a ‘glass cockpit’ featuring digital electronics and color displays enabling two-crew operation. A faster cruising speed than previous versions shaved 20-30 minutes off the flying time between Tel Aviv and New York.

The stretched upper deck of the 747-400 increased seating capacity. Becoming one of the first airlines to do so, EL AL fitted a personal TV monitor to each seat allowing passengers to select movies or other entertainment, as well as the Rockwell Collins Airshow that displays route maps, speed and other flight information.

Importantly for EL AL, the 747-400 featured a significant increase in range, to about 13,350km (8,300mi), which enabled nonstop service from Tel Aviv to Los Angeles.

Cargo

EL AL’s cargo division continued to grow during the 1990s, both in tonnage carried and in its reputation for excellence and ability to carry items of unusual size and weight, from special offshore drilling equipment for installation in the seas off Alaska to heavy electrical generating equipment to animals to sensitive miniature electronic goods. Israel’s rising overseas trade also contributed to this growth.

In November 1991 EL AL opened a new cargo terminal at Miami International Airport, to better serve the expanding market between Latin America and Europe. The structure boasted the largest cooling capacity for perishables of any air cargo carrier operating between Europe and Miami.

EL AL continued its practice of converting 747s to meet seasonal demands and political influences on traffic. A passenger 747-200B (4X-AXH) was converted in 1993 to a combi with a side cargo door.

In July 1994 a new computerized software system was introduced that calculates the space needed and enables the airline to program the loading of 100 tons into a 747 in only 20 minutes, saving more than one hour of ground time. Weight and balance calculations are performed simultaneously.

Two 747-200 freighters (4X-AXK and 4X-AXL, formerly operated by Singapore Airlines) were purchased in January and March 1995. This brought the number of 747Fs to six: three all-cargo and three passenger/cargo combis.

By 1996, EL AL offered cargo service to 50 cities on four continents and was the only airline operating 747 freighters directly between Israel and the US (New York, Miami, Chicago and Los Angeles). European freighter destinations included Amsterdam, Brussels, Luxembourg and Cologne. That year, an all-time high of 211,000 tons was carried, and cargo provided close to 25% of the airline’s revenue.

Competition and Challenges

The first three years of the 1990s witnessed a worldwide aviation recession, caused by the Gulf War of 1990-91 that resulted in sharply reduced passenger traffic, as well as severe increases in aviation fuel and insurance costs. Total losses by members of the International Air Transport Association (IATA) ranged from $2.7 billion in 1990 to $5 billion in 1992. Several US and European airlines failed.

Against this background, EL AL’s performance in each of those years stands in marked contrast, with annual profits of $14 to $38 million. In 1992 IATA ranked EL AL as one of the three most efficient airlines in the world.

On 1 January 1993 the European Community nations further liberalized their air transport policy. Allocation of seat capacity among airlines and deregulation of prices became unrestricted, resulting in increased competition. Available seat capacity, which had increased by 24% in 1992, continued to rise. While demand started to recover, it was not nearly enough to fill the extra seats. As a result, air fare price wars became widespread.

Several more airlines started operating to Israel in 1993, including western and eastern European scheduled and charter companies. The charter airline market share in Israel grew that year to 15% of the total.

In early 1994, the Israeli government liberalized its own aviation policy, based on the principle of ‘open skies’. This enabled airlines to set their own fares and increase capacity, and allowed charters greater access to the Israeli market, resulting in accelerated capacity growth and aggressive fare competition. Foreign charter airlines increased seat capacity by more than 40%, far in excess of demand, triggering a vicious price war, particularly within the domestic market. This process further shifted traffic from scheduled to charter airlines, which further increased their Israeli market share to 16.5% in 1994.

EL AL introduced a new business policy to adapt to the challenging conditions, based on competitive marketing, increased efficiency and reduced production costs. Fortunately, positive economic and political factors saw air travel to Israel grow by 15% over two years, with a 65% increase in overseas travel by Israeli residents. Also, the air transport industry as a whole saw passenger numbers increase by 8% and international cargo expand by 14% in 1994, reflecting at last an economic recovery. As a result, in 1994 and 1995 EL AL enjoyed its eighth and ninth consecutive years of profitable operations.

More difficult times returned in 1996, as passenger traffic to Israel fell, and the price of jet fuel rose by 21%; seat capacity rose 5%, and air fares dropped by 6.5% in real terms. EL AL complained that the government failed to ensure fair competition and equal opportunities for Israeli airlines. Nevertheless, EL AL coped by adjusting available seat capacity, schedules and manpower, and by renewing the emphasis on customer service.

Privatization Considered Anew

In June 1994, the Israeli government decided that EL AL should be privatized, both in order to compete better and to yield needed funds to the state treasury, and the Boston Consulting Group was hired to value the airline. The consultants estimated a price of $385 million, noting that EL AL ranked among the world’s best airlines. Recommendations were also made, including the cutting of nonprofitable routes such as Cairo, Sofia and Lisbon; improving first and business class service to the United States; inter-airline passenger agreements (so-called ‘code-sharing’), particularly with US carriers; and increasing direct sales and business class traffic. The government studied the report and authorized a prospectus that would furnish information to potential investors relative to an offering to sell EL AL stock to the public.

To support privatization, the government acted to end the 12-year period of temporary receivership of EL AL, so that the airline could operate as a regular commercial company. This occurred on 14 February 1995, with the simultaneous appointment of a new board of directors. Yosef Ciechanover, former chairman of the board of Israel Discount Bank, was appointed chair of the board; Rafi Harlev continued as president. It was anticipated that an offering of EL AL stock could be made on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange by 31 May 1995 and on the New York Stock Exchange within a year thereafter.

The process faced one delay after another, however. Government officials hedged over a perceived lack of interest in the investor market for an airline that operated only 306 days a year because of the Jewish Sabbaths and holidays. Underwriters debated the estimate of the airline’s value. The result—nothing happened.

The Rafi Harlev Era Ends

Rafi Harlev, who had steadfastly contended for many years that the airline had to be privatized in order to survive in a more competitive world, grew increasingly frustrated over the government’s repeated postponements. Finally, on 26 March 1996, he resigned his position as president.

Thus Harlev concluded 14 years at the helm of EL AL—the longest anyone had served as president. He guided the airline during the entire difficult receivership period that started in 1982, and contributed greatly towards its transformation as a struggling, unprofitable enterprise to a competitive, profitable, major international force, serving destinations from Los Angeles in the west to Hong Kong in the east.

Harlev agreed to stay on as caretaker executive until a successor was appointed by the transport and finance ministries and approved by the full Israeli Cabinet. That would come in September 1996, starting a new era for EL AL—a period in which three successive chief executives would steer the airline through changing times (Chapter 9), until the end of 2004 when the long-sought privatization would finally become a reality (Chapter 10).

[EL AL: Israel’s Flying Star — end of Chapter 8]

Copyright 2017, 2021, Marvin G. Goldman